Carson Daly and the Theory of Relativity

Minnesota band Low goes on the late night show "Last Call with Carson Daly." Chris Godsey was there and recounts the weirdly banal glory.

Pop culture worlds collided last Wednesday when the Duluth band Low taped a performance on the NBC late-late-night show Last Call With Carson Daly.

A band playing on a television talk show is not weird. Low playing Carson Daly’s show is weird as hell, like if the Replacements had played Johnny Carson, The Talking Heads had been on Mike Douglas, or godspeed you! black emperor were booked on Oprah. It’s like art that intentionally offends convention—Piss Christ, maybe, or some freaky Mapplethorpe–being placed in the lobby of an Olive Garden. It’s like Matthew Barney becoming a greeter at Wal-Mart.

It’s like…no, it is a weathered icon of the artistic fringe showing up smack-dab in the middle of the mainstream.

Low (Al Sparhawk and Mimi Parker of Duluth, Zak Sally of Minneapolis) spent the first decade of its career (1994-2004) playing unusually slow, quiet, intense music, developing a significant global audience, and avoiding mainstream fame. The band’s songs have been used on MTV’s The Real World and a GAP commercial, and a song by Sparhawk and Parker is a prominent on the soundtrack to the Richard Gere movie The Mothman Prophecies. They’ve opened for Radiohead, worked with superstar producers and been praised by people who understand music better than even the most snobbish among us think we do.

They’ve been legitimate indie rock stars since the mid-1990s, and their new record, The Great Destroyer, has been lauded in Rolling Stone, Spin, Playboy (four out of four bunnies!), Blender, Paste, et al., and been riding high—including a few weeks at number one—on the college music charts, and their new label, Sub Pop, has the money and clout to promote them in ways more prominent than they’ve ever been (or maybe wanted to be) promoted.

But they can still walk down the street in their hometowns and most other cities. They load and unload their own gear in and out of a simple cargo van (although a low-end tour bus could be coming). It’s not odd to see them behind the merchandise table at their own shows. Even in Duluth and Minneapolis, many culturally literate people have never heard of Low.

Last Call premiered in 2002, after Daly left his original TV gig, hosting MTV’s Total Request Live—or “TRL,” if you’re over 40 and don’t want to sound stupid mentioning it to your kids. Both shows are mostly about helping famous singers and actors promote their latest projects. Daly dates movie stars and shows up in People magazine. He can be pleasant like Johnny Carson, but he’s much more snarky and not nearly as naturally funny. Sometimes he comes off as terribly sycophantic, especially when he attempts to use hip-hop slang while talking to black dudes, but just winds up sounding like any other square white boy who desperately wants to be down. When I taught at UMD, my hip, culturally snobbish students referred to him as a “tool.” I concurred. They also obviously envied his privileged place among famous people. Me, too.

Confirmed ticket holders and people waiting stand-by were allowed to show up on the mezzanine level of NBC headquarters at 5 p.m. for the official 5:45 “arrival time.” By 6, a “confirmed ticket” line was at least a hundred people long, a separate line for stand-by hopefuls was approaching 30 people, and the handful of pages who literally kept everyone in line could be heard chatting about another queue one floor below.

The pages and their uniform—black shoes, charcoal slacks or skirt, blue blazer, white shirt and stylized peacock tie—would look familiar to anyone who’s seen them included in pieces on Saturday Night Live, or remembers that they were frequently used on Late Night With David Letterman before he moved to CBS in the early ‘90s.

Around 6:15 the mezzanine folks were herded down a flight of stairs, through a metal detector, into a temporary queue for a few moments. Like an apparition, Jane Pauley strolled by, eyes forward, gait brisk, then was gone; she’s got a new day-time talk show, and rumor has it pages were propositioning NBC Store patrons with tickets to the show earlier in the day. No word on whether they successfully filled all the seats. After a couple minutes, the herd was moved forward another 15 feet, into a final hallway line before the show. The hall, which was lined with signed photos of Saturday Night Live hosts, led into studio 8H, where Last Call is taped, and where SNL is rehearsed and performed.

Lots of people wearing microphone headsets and laminate ID badges bustled up and down the hallway, in and out of the studio and other doorways, around corners and back again, always looking concerned and industrious. More of them showed up every few moments, till it seemed like a few were there just to lend an air of gravity to the situation. Audience members were seated by 6:45 or so. Inside the studio, more apparently official people did more bustling, but faster, with more, almost comical, gravitas.

The stage and floor managers both addressed the audience—showed how and when to provide applause, described how the show would proceed, repeated that anyone taking pictures or shouting random comments would be removed, “No questions asked,” by security. A couple big, grim dudes in suits illustrated the seriousness of such rules.

Daly appeared onstage, looking far more slim and handsome in real life than he does on TV, and warmed up the crowd with a few jokes, more instructions, and some banter. “What are you doing after the show?” a woman from the balcony at stage left yelled. “Going out with you,” he immediately responded, before turning to the right and stage-whispering, “Weeirdooo,” to much laughter. Then he disappeared offstage.

DJ Reach spun frenetic top-40 rock hits and house band (for that week) Government Mule worked to get the crowd even more warmed up, and at 7, amid frantic applause led by the stage manager’s exhortations, Daly came out and delivered a few bland jokes about Martha Steward being released from prison, the aftermath of socialite Paris Hilton’s electronic e-mail and phone number lists being stolen, and other current events.

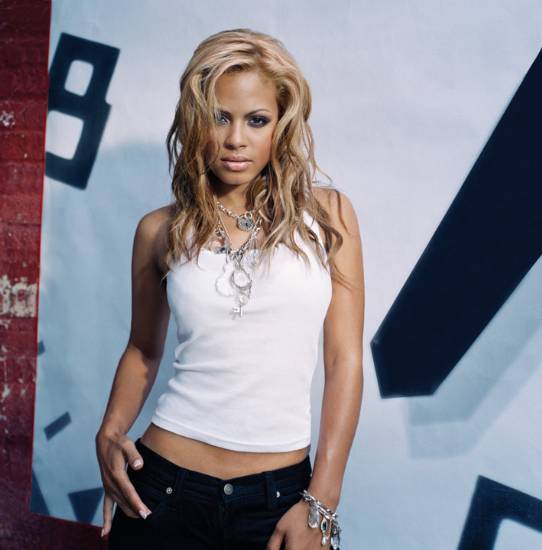

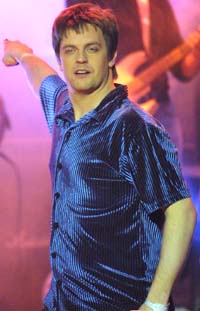

Actor and singer Christina Milian came on to promote the movie Be Cool, which also stars John Travolta, Uma Thurman, Cedric the Entertainer and a bunch of other people. Milian is a cocoa-colored confection with Bridget Bardot sex kitten hair. Daly’s conversation with her was boring but inoffensive. She’s breezy and bland but not vapid, bubbly but not quite charming. Comedian Jim Breuer seemed stoned (he always looks and sounds stoned) and did his “heavy metal comedy” schtick while talking about his daily show on Sirius Radio. He got a few belly laughs, and came off naturally while talking to Daly—it almost seemed like a couple guys just hanging out, trying to make a girl laugh by being a little gross. It also seemed that Daly and Breuer probably wouldn’t really hang out if one of them didn’t have a TV talk show and the other didn’t have a career to promote.

More surreal than seeing famous people in the flesh—and that’s plenty surreal, confronting the concrete human existence of what seem like fictional characters, especially in a pop culture-saturated world where reality constantly becomes less real—was the show’s physical scale. Framed on TV screens, even big ones, talk shows seem somewhat cozy, like a couple people having an intimate chat that just happens to involve a couch, a desk, and a studio audience. While in the studio, at least in 8H, the set is stuck out in space, as if a desk and a couch had been placed at center court of a high school gymnasium, the stands had been filled, then two people decided to pretend like they’re good friends. The artifice of television, as it’s being accomplished, is both fascinating and disappointing. Rhetorical wonderment like, “Wow, this is how it happens!” gives way to dashed innocence and naivete: “That’s how they do it? Oh.”

After Milian and Breuer were dismissed, Daly taped a brief lead-in to Low’s performance, something like: “Our next guests have had the number one record on the college music charts for the last four weeks. Here to perform the song ‘California,’ please welcome Low.”

The next 10 or 15 minutes were spent getting the floor and balcony audiences arranged around the performance stage. Low looked nervous. Sparhawk was tightly wound, like he just wanted to play instead of standing still; he took deep breaths and blew them out deliberately, strummed on his guitar a couple times, explained to the audience—at least those who could hear him over the din of moving, waiting people—that it was his daughter Hollis’s fifth birthday, and his and Parker’s 15th wedding anniversary. Everyone who had heard him applauded. Parker stood almost completely still behind her drum kit; she always seems less anxious than Sparhawk or Sally.

As the wait dragged on, Sally noticed that Chad Salmela, who lives in Duluth, was standing in the front row and wearing a Low t-shirt. “You’re the only person here who knows who we are,” Sally said with a half-laugh.

Then, suddenly, they were playing.

The studio version of “California” is three minutes and 23 seconds long—an impossible amount of time for any band, even with lots of warming up, to find, catch, and ride any sort of groove in front of a live audience. Tension was palpable in Sparhawk’s voice, which started out shaky, and not in the artful way it often quavers with emotion or anger.

But Sparhawk found his voice. Parker’s harmonies came in like liquid, the playing was tight, and the song was done justice. It’s a good tune for introducing Low to a new audience, catchy enough to fit the context of a late-late-night show with a party atmosphere, and one that veteran fans of the band won’t consider evidence of selling out.

After it was over Sparhawk could barely talk, out of both obligation and exhilaration: gear had to be broken down, lots of people were waiting, and sometime, somehow, the artistic and professional and personal enormity of what his band had just done—what it’s been in the midst of for the last two months, and what it’s done in the last decade–would have to be acknowledged and made sense of. He was smiling and stammering, literally being turned in all different directions, as the crowd filed out and left the studio empty.