Body Whirled

Suzanne Szucs is thinking about science and art. In this post-da Vinci world, what different mysteries do they claim, what technologies differentiate them?

There’s an exhibit at the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago called “Body Slices.” That’s exactly what it is, vertical slices of a man and horizontal slices of a woman, for some variety, I suppose… or vice versa, I don’t quite remember. When I lived in Chicago while attending the School of the Art Institute, this exhibit was an insider secret – we art students would pilgrimage down to the museum in Hyde Park – virtually the only time we would venture to the south side of town except for the occasional jaunt to the Tiki Bar. In those days the slices were kept a little out of the way in the stairwell. It was something you could inadvertently happen upon and be shocked by if you weren’t prepared for it – frankly, the museum didn’t really seem to know what to do with it. Those slices of anonymous persons were made at a point in history that we might now be a little ashamed of. In fact, tales were told of visitors who had stepped back out of disgust and fallen down the stairwell … apparently prompting the museum to either move the exhibit completely out of sight or clean it up a bit. By the looks of their website, they took the latter route.

Another curious place to visit, beloved of art students, is the Mütter Museum in Philadelphia. Billed as “disturbingly informative,” the museum, which is a branch of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, is full of preserved anomalies – enlarged hearts, conjoined twins, a cancerous growth removed from President Grover Cleveland and, my favorite, a cabinet containing over 2000 inadvertently swallowed items (later extracted one way or another). The Mütter Museum is a sanctioned freak show and as our corporeal selves fascinate us all, only the very faint of heart would miss a trip there.

As artists, we are particularly interested in our bodies in an endless investigation as to whether there is soul in there. At the same time, we are bounded by a curious social taboo over looking too closely. Any artist attempting to use real cadavers in their work faces a difficult road and a lot of questions. A scientist, however, has a different passkey, a sort of legitimacy that comes from being an aid to the common good.

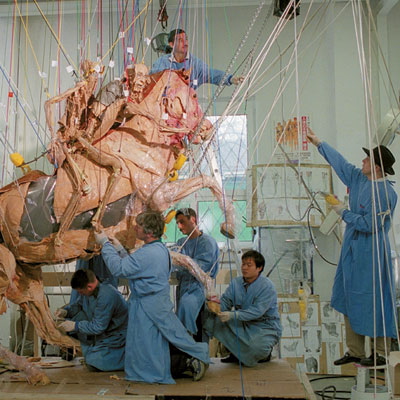

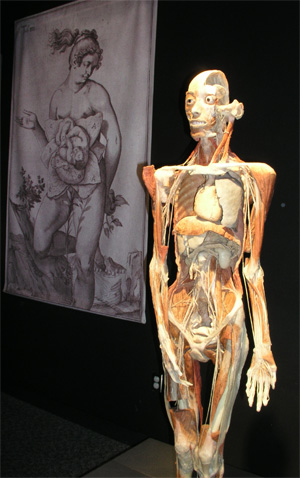

This leads me to “Body Worlds: the Anatomical Exhibition of Real Human Bodies” at the Science Museum of Minnesota. The exhibition has taken on those taboos of looking too closely and is attempting to demystify the body by presenting an updated version of cadaver inspection for the general public by featuring bodies stripped of flesh to reveal skeletal, muscular and nervous systems that are displayed in various poses. The exhibit is the life’s work of German anatomist and scientist Dr. Gunther von Hagens (who incidentally, for all you artists out there, looks remarkably like Joseph Beuys, or maybe it’s just the fedora). Von Hagens invented a process called “plastination” which involves injecting tissue with liquid reactive plastics to prevent it from breaking down and decomposing. The result is color-injected muscle that, yes indeed, looks like vibrant beef jerky.

I certainly have corporeal fascination, but what really interested me about seeing the show was all the art rhetoric that surrounded it. Laurence Liss from Art Matters Magazine noted, “ Just as the bodies (in the exhibit) blur the lines between life and death, the exhibit as a whole blurs the line between science and art.” This I needed to see, because we have a huge history of science and art co-mingling. Just say da Vinci. Certainly my field, photography, has grappled with those twin beasts since its inception, its invention actually freeing other disciplines to shed scientific inquiry in favor of concept. But artists have continued to wrestle with the corporeal within their work. The recent Kiki Smith show comes to mind, as does photographer bad boy Joel-Peter Witkin, who probably got locked in the Mütter Museum overnight when he was a boy.

Religion intersects with art also as it searches for divine intervention in the body – are we made in His image or aren’t we? Andres Serrano put that challenge out there with the photograph “Piss Christ” in 1989. If we are made in God’s image, then isn’t even our piss sacred? Not for many viewers, apparently, as Serrano’s image caused a rage that brought out the veins in Jesse Helms’s temples. For myself, I have never seen anything so physically brutal as the sculptural depictions of the death of Christ in the Cathedral in Mexico City. In opposition, the withered hand of St. Stephen is tenderly displayed within a golden reliquary at the Cathedral bearing his name in Budapest. Despite his scientific affiliations, an ethics committee had to be brought together to determine whether the von Hagens exhibition featuring real human bodies (willingly donated) had gone too far. Nevertheless, he was asked to plastinate the heel bone of St. Hildegard of Bingen, although performing the procedure on the entirety of Pope John Paul II didn’t quite make it out of committee.

I can’t seem to get to a point in this column, because I am not sure I can tell you exactly how I felt about the Body Worlds exhibition. I really appreciated the comment I read from one of the donors: “Sadly, many of us know more about our cars than our bodies.” I agree with that statement completely, but the truth is, I didn’t feel like I really learned a whole lot about my body through the exhibition. Because the Science Museum is a learning institution, there was a great attempt to provide knowledge to the audience, but the plastinates themselves, in trying to be unusual, or interesting, almost defied that goal.

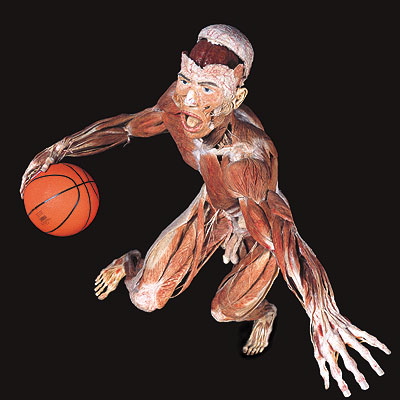

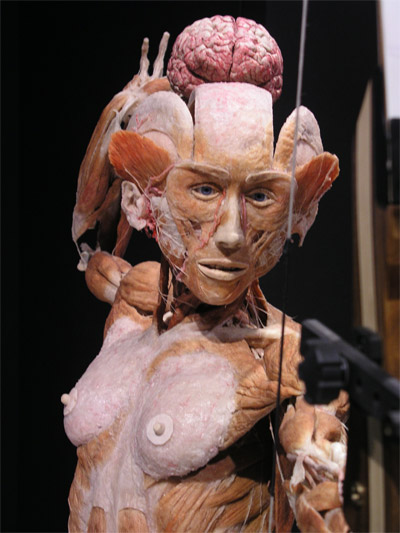

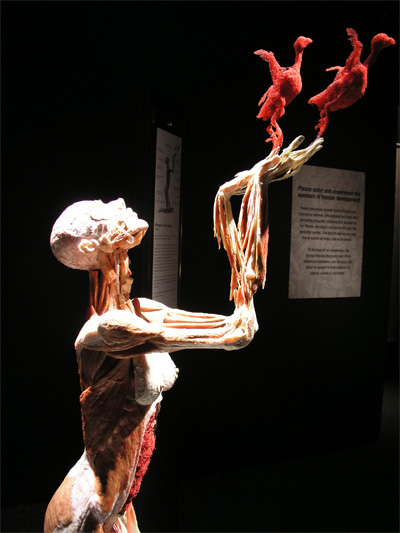

First, I didn’t get a sense that they were real. Sure, there’d be rare instances when something would spark recognition, like a tooth out of place, or some hairs that hadn’t been clipped. But in general, with the full plastinates, they were so pumped with color or artificially displayed that they seemed like plastic models. A flayed body dribbling a basketball, or a runner displayed so that it seemed as though his muscles were flying off his body, reminded me of early Renaissance etchings when the body was being systematically explored but not quite understood naturalistically. In Pallaiuolo’s “Battle of the Ten Nudes” (1465) he shows each rippling muscle uniformly and impossibly flexed, resulting in figures that look like lifeless paper dolls. The reclining figure of a pregnant woman mimics the classic odalisque, but her belly is splayed open to reveal the child in her womb – it’s everything that’s wrong with an odalisque and more. Brain caps removed, spines hanging out of the back of bodies – from an educational point of view, what von Hagens has done with the bodies makes little sense to me, and from an aesthetic point of view I had a hard time getting there. Yet he fits into tradition and most visitors I have spoken to find it fascinating. So what’s wrong with me, what am I missing?

Of course, I was looking at the exhibition from an aesthetic perspective, but I would argue that a condition of existence is change and decay. The plastination process had drained both the life and the death out of the subjects and replaced it with red dye number something. Walking around looking at these figures, it was as if they wanted to decay, but were caught in this artificial limbo. The major difference between the slices in Chicago and the ones in Body Worlds (yes, they had slices too, but encased in plastic) and the material at the Mütter Museum is that those continue to deteriorate, even within their preserving materials. It is this witnessing of the life of decay which equals death (we are all dying every day) that brings us the philosophical lesson of our mortality.

There were noticeable exceptions to my aesthetic criticisms, in particular the technique by which dyes were injected into blood vessels and hardened so that the figure of the individual or creature was preserved. Here the artificial red color created a transcendent quality – it highlighted so well the minutest details that the subjects were at once tender, fascinating and impossible. Indeed, their relationship to the natural world, to root systems and plant structures was undeniable and remarkable. They remained a mystery – “How could that be?” – even as their presence explained a system to me. A death mask, inexplicably gold leafed, that spun around so you could see the back of the face had the same effect on me – it reached into my curiosity.

So I must correct my previous statement: I did learn through Body Worlds, but not what myself or the museum, but perhaps von Hagens, expected. I learned how art in its connection to science functions for me – that learning, even or maybe especially scientific learning, is facilitated through aesthetics, it doesn’t need to be dressed up with scientific function to communicate perhaps the most important messages, but it does need to make me curious. Von Hagens wants you to question your philosophical existence through the corporeal, through his obsession. In this context it is quite an artistic statement. Unfortunately, the museum (and I mean any museum, with the possible exception of the Mütter) has the tendency to dumb stuff down into superficial textbook chatter. Unlike da Vinci’s day, we don’t look at art as science or science as art or clearly see the connection between the two (why else would art programs always be the first budget cuts in education?). Von Hagens, to his credit, is trying to stir the pot and the overwhelming success of his exhibition suggests that he is succeeding not a little.

For me, I find St. Stephen’s gnarled hand or a reliquary full of Santos Mistos (mixed saints) more inspirational because there is living ritual within their context; because we are more than matter. We are also something indistinguishable we usually refer to as soul. I find the Mütter Museum more intriguing because the exhibits there express how little control we have over the mysteries of life, how little we actually do know, so it leaves room for my imagination. I saw in Body Worlds a representation of our contemporary society, one obsessed with a narrow definition of perfection witnessed in the national push towards testing, plastic surgery, anti-bacterial, anti-ageing, anti-intellectualism, anti-curiosity and anti-emotionalism.

Post-Body Worlds I walked over to the Minnesota Museum of American Art (ok, they get an exemption too) to see the “Ever More” show. There were some amusing similarities, including a large hanging piece consisting entirely of plastic cable ties called Plastic Atmosphere (Trever Nicholas), which reminded me of the blood vessel pieces of von Hagens. Walking through “Ever More” was a relief, a reminder that learning is about questions, not answers. It made me wonder how I would have responded to Body Worlds if it had been presented with more mystery, less systematically, with more provocative questions… in an art gallery.