Blooming Possibilities: Beauty in Botanical Art

Alex Starace visits the Bell Museum of Natural Historys exhibition, Bloom! Botanical Art Through the Ages, and finds a lot to like and a lot to learn about the diversity of art. The show runs through August 27.

Thomas O’Sullivan, curator of “Bloom! – Botanical Art Through the Ages,” asks: “Will twenty-first century tools such as digital imaging and plant genetic research make botanical art seem obsolete?” It seems quaint he even bothers posing the question. Of course they will. Botanical art has been nearly obsolete since the 1960s, and, really, it’s been struggling since the invention of photography. Now, with the proliferation of digital imagery and scientists’ ability to change plants at will, the form is, if not already dead, on an operating table in the ER – or, at least, this was my response before attending his well-curated exhibit at the Bell Museum of Natural History.

In “Bloom!” O’Sullivan convincingly demonstrates the dynamism of the form, as well as its aesthetic charms. The exhibit displays botanical art from the fifteenth century all the way through the twenty-first and is particularly good at juxtaposing similar-looking paintings that happen to be separated by several centuries of time. The result is that the gallery-goer can see what was so evocative in the earlier (in some cases, nearly-medieval) works, while understanding how moderns have appropriated and used the form. For example, John Stuart Ingle’s Still Life with Yellow Zinnia, a watercolor from 2000, is hung right next to Maria Sibylla Merian’s Inflorescence of Banana, a hand-colored etching and engraving made in 1710. Without looking at the placard, it’s impossible to tell the age of Merian’s work – the coloring and detail are very well preserved, and the green-red-green-yellow segmentation of the banana plant matches our contemporary sense of beauty. Clearly, then, Merian’s Inflorescence, with its focus on one centrally placed plant, foreshadows the calming effect of Ingle’s work.

In Ingle’s Still Life with Yellow Zinnia, he gives us a birds-eye view of a table, on which sits a cloth napkin, on top of which sits a bottle, holding a zinnia. In the upper left corner is a bit of a basket holding another plant, and on the right side are some ropes forming a pattern. The style is not-quite-photorealism-with-a-touch-of-impressionism. The composition, with the two peripheral elements (other plant, rope) decorating the framed main element (zinnia), is impeccable. The lightness of the piece, along with the coloring (brown of the table, off-white of the napkin, dab of yellow zinnia) are appealing, uplifting, and eye-catching. The piece is tight enough that it’s difficult to describe exactly why it’s so effective: Is it the composition? The coloration? The subject matter? The painterly skill? …Probably it’s all of them – a perfect synthesis of several important aspects.

However, the effect of the painting is easy to describe: it gives an overwhelming uplift. This, one is reminded, is what painting used to be – this is pretty damn great. It’s as if (and such an occurrence stunned this reviewer at the Sheldon Memorial Art Gallery in Lincoln, Nebraska) you were looking at a series of modernist works (Rothko, Motherwell, Kline, etc) and then, in the midst of them, was placed a nice Norman Rockwell painting. All of a sudden, Rockwell doesn’t seem so stodgy – in this context, he’s the outlier, the daring painter. You think to yourself, It’s strictly representational! That’s pretty fantastic – this is very, very good! Similarly, Ingle’s work takes advantage of a defamiliarized, twenty-first-century viewer to show him or her that still lifes used to be popular for good reason – good composition, the exposition of superior technique, and the portrayal of a beautiful scene have their charms. It catches a savvy, contemporary gallery-goer aback. Here we have something that we thought we’d moved past, but in actuality haven’t – someone’s still doing it in earnest, and doing it well.

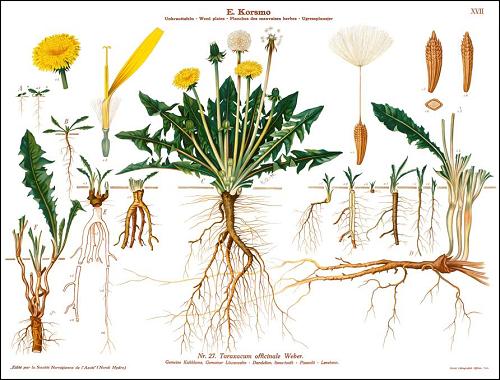

Perhaps most exciting is that Ingle follows some of the botanical art rules that have been observed for centuries: he displays the flower prominently and obviously, he gives careful and accurate details, and he makes the coloring, in combination with the background, as appealing as possible. Throughout the show, there are several commonly followed motifs that make the images from all eras compelling. The first of which is that most flowers are drawn on a pure white background – in other words, there’s no depth to the picture, or context – just the flower. For example, in Marilyn Garber’s Blechnum Spicant, a watercolor from 2006, the roots of the plant are prominently displayed, floating on white. The result is a weedy, lattice-like design that stands out because of its contrast with the cream background. Similarly successful is Emil Korsmo’s Weed Plates, a chromolithograph from ca. 1935, that displays various weeds placed on a white background.

Aside from foregrounding the shape, botanical artists also display the patterns and textures of plants. In Basilius Besler’s 1615 engraving, Flos Solis Major, he gives us a very large, black-and-white image of the eye of a sunflower. The concentric patterns formed by the grains create a spiraling, mesmerizing image that’s on par with the abstractionist work of any era. Another common motif is the insertion of an insect, bird, or garden animal to liven up a painting. In Mark Catesby’s Wampum Snake with White Lilly, a hand-colored etching, ca. 1740, an aqua-blue snake twists back on itself to add both color and design to what would otherwise be a fairly bland piece.

However, despite the enjoyable insertion of creatures and the frequent occurrence of abstraction within the design of a plant, most botanical art (at least until the twentieth century) served first as instructional, academic, or promotional material (in either a gardening book, a botany tome, or a seed catalogue) and second as art; the plants dictate the abstraction and related creatures, not the other way around. As artist Wendy Brockman is quoted as saying, “If you’re not going to paint something faithfully, pick something else.” This, it seems, is the ethos of the traditional botanical artist. Which makes it easy to judge if a piece of botanical art is successful: Does it look right? Does it show the proper details? Is it accurate? If yes, then yes – the painting succeeds, at least on the terms under which it was created.

But viewing botanical art as regular art – the kind that’s hung in art galleries and art museums – is a tad more difficult: Is this innovative? Does it address cultural issues? What is it attempting to say? These are the sorts of questions usually asked of “serious” art. And therein lies the problem: applying such questions to botanical art would be rather foolish. Perhaps, though, this indicates a problem not with botanical art, but with the current ideas of the meaning and importance of art. Since when has art become so restricted and limited that only pieces created specifically in the name of the inscrutable and ineffable Art (with a capital A) can be taken seriously? Perhaps (and this is probably the greatest success of the “Bloom!” show) botanical art allows us to see in wider terms the fairly specialized, niche-filled field of contemporary art creation.

In botanical art, one sees work created by those who are interested in things besides just art. For example, in “Bloom!” there are displayed a dozen or so “plant models” that were common in University of Minnesota botany and biology classes in the early half of the twentieth century. The models are life-size, made out of metal, and painted the bright colors proper to each plant. These models can be disassembled, revealing each model’s piston, stamen, etc, so that students can learn about the structure and reproduction of plants. The models clearly have utilitarian purpose – in fact, this seems to be the only purpose for which they were designed. And yet, with their bright, smooth surfaces and size, they’re faintly reminiscent of the hard vinyl Lowbrow art toys that are currently quite popular. To state the obvious: aesthetic pleasure is not purely the domain of art-objects. For example, in The Illustrated Guide to Edible Wild Plants, put out by the U.S. Army, one finds many appealing photographs, such as those of the death lily, and of the wild crab apple – but it’s a field guide, not an art book.

Or, for an example of the obverse, look no further than William M. Harlow’s book, Art Forms from Plant Life (1966). (Incidentally, neither this book nor the U.S. army guide are in the “Bloom!” show, though both would fit right in.) Harlow, a professor emeritus of environmental science and forestry, appears to have little to no artistic background. However, he noticed, in the course of his work, that the magnified images of plants reveal quite fantastic patterns, ones that most people miss in their day-to-day lives. So he decided to make a book of these images, just because he could. As a result, he gives us photographs such as Chestnut Bur Spines, X 8 and Fruit Surface of Osage-Orange, X 6 which reveal rich patterns, just like Besler’s Flos Solis Major.

And so, in botanical art, we have non-artists creating works of art, and non-works of art being viewed artistically. The idea is rather liberating and reminds us that some of the great artistic innovators weren’t artists. For example, in photography, one ought be reminded that Harold Edgerton, famous for his photograph of the splash from a drop of milk (Coronet), was, and always was, an engineer. As relates to the “Bloom!” exhibition, the curator O’Sullivan does a good job of opening up this world of practicality and dilettantism – of showing a broad range of influences and types of art. We see that many botanical artists, at least until recently, didn’t aspire to be hung in galleries. Ironically, though, the current botanical artists (there are a significant amount of contemporary pieces, many of which I’ve not touched upon in this review), are different: almost all of the contemporary pieces are art for art’s sake. For the first time in the form’s history, there’s little other reason to make botanical art.

So, to return to O’Sullivan’s original question: “Will twenty-first century tools such as digital imaging and plant genetic research make botanical art seem obsolete?” the answer, unsurprisingly, is mixed and complicated: Yes – botanical art is obsolete in the sense that there’s no longer any need for exact paintings of plants. But, also: No – for the first time artists are making botanical art for art’s sake and are thus able to innovate and fudge in ways that previous generations of botanical artists were unable to do. …So is this good or bad? Does it betoken the end of the form, or a new revolution? It’s certainly not a foregone conclusion that art for art’s sake will equal better art – there’s a lot to be said for having to work within a set form. Regardless, one thing is for sure: the current “Bloom!” exhibition gives a good account of the history of the form and reveals a surprisingly large number of exciting pieces.