Bidding Adieu to Ayesha Adu

An investigation of self-portraiture that spans three decades, transformations of gender and identity, and revolutions in self-love

This piece mentions attempted suicide and describes physical abuse.

As with the first essay, there is a song to accompany this essay. Please be sure to listen. Thank you.

Embers

Ayesha Joyce Fowler aka Ayesha Adu aka Atlas Oggún Phoenix

When I graduated from Dialectical Behavioral Therapy (DBT) in April 2021, each member of the group was asked to describe me in one word. Among the words were “forager,” “thoughtful,” and my therapist chose the word “inculcate.” I told them how wonderful it was to get to know each of them and hear their stories as I watched them thrive. I later celebrated by making myself a wonderful meal and, for the first time in a year, I enjoyed a glass of wine.

As I began to look up articles about Black and biracial transmasculine people, there was precious little to be found. After much reflection and learning, and my latest film, Do I Qualify for Love?, having entered its first film festival in Birmingham, England, I decided to create a documentary about my transition.

I wanted to capture my transition and create something that went beyond YouTube explanations and vlogs. I am a cinematic creature. I understand cinematic language and the power of telling a story through the use of lens, color, music, and editing. I decided to create something beautiful, raw, and reimagined. My new, unprecedented film, Beautiful Boi, is a transmasculine story of self-love, flight, and transformation in my 50s.

The film will be part documentary and part experimental narrative. The documentary will be in black and white, and the experimental narrative pieces will be shot in color to create fragments of memories, in which I revisit certain times in my life at various ages. I will also appear in these pieces as myself in the now, as a guide to my younger self.

The dominant narrative of most transmasculine stories are told by young white people. According to the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey, over 50% of the African American transgender population has attempted suicide. The number is higher for disabled African American transgender people. I am Black/biracial. I am trans. I am disabled. I am on disability. I live below the poverty level. I am struggling. I am not alone.

One of cinema’s superpowers is that one person’s personal story can serve as another person’s survival guide. The power it takes to transform yourself into the vision your soul has for you takes resilience, perseverance, and a lot of love.

SLOW FADE OUTTenderly embracing my face, I’m in a long, sweet, and tender kiss goodbye to Ayesha Adu.

SLOW FADE INReborn, naked, and unveiling my soul, I am…Atlas Oggún Phoenix.

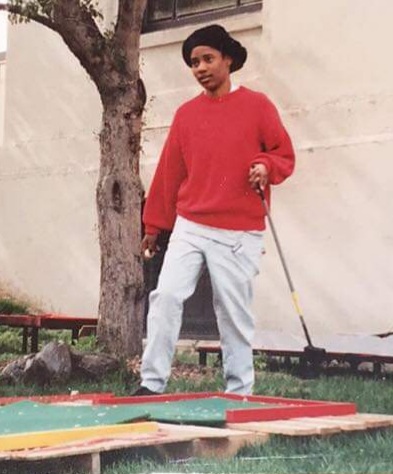

Tender Boi, 1991

This picture was taken by a dear friend I didn’t know at the time. She took the photo, because I was playing on the mini golf course she made. We met formally in 2017 as cast members of the venue we performed for. One random day last year she sent me this photo. Here, I am 20 years old. I made that hat. This was my favorite outfit. I felt masculine, strong, and protective.

It was my first year in Minneapolis, Minnesota. I came from Ohio to study film at the Minneapolis College of Art and Design. I saw the name of the school in a dream when I was 16. I felt this was my destiny.

But I flunked out, because I couldn’t afford to pay for my art supplies and create the work I needed. The tuition went up $3,000 over the summer before I started. It was the hardest year of my life at that time. I recently realized that I have been poor for 95% of my adult life.

Queen for a Day, 1992

I am 21. I was going to see Queen Latifah at First Avenue in downtown Minneapolis. My friends thought I should dress up and look nice for once. They gave me a makeover. The earrings, clothes, and shoes were borrowed. They fixed up my hair and gave me a little makeup. It was nice to dress up. But it wasn’t me.

Searching for the God Within Me, Self-Portrait, 2002

I am 32. I am taking photos of myself for the first time since my days at MCAD. I am sitting in a bubble bath. The camera is on my tripod. I wanted to see who I was, if there was anything special I could find in myself. I didn’t see anything at the time. Self-actualization takes work.

Lost Summer, Self-Portrait, 2007

I was 36. I was on my way to a queer nightclub, Pi, in south Minneapolis for Pride weekend. I was awkward, unsure of myself, and I had never had a partner. That night I had a date. I was concerned that I wouldn’t be special enough to capture her attention for a sustained amount of time. I thought I was boring. All I ever seemed to talk about were films.

I think about how I have always struggled with my masculinity. I tried being hyperfemine, because it seemed more socially acceptable to be with other women as another fem. The masc-of-center women I did meet seemed angry. I couldn’t understand the anger. I am not an angry person. I am not entirely soft either. I tried being a tomboy-fem. I tried being what is referred to as “butch.” But “butch,” “soft butch,” or eventually, “masc-of-center” didn’t seem to fit me. These identifiers felt forced, cold, and perfunctory to me in regards to my personal identity. They may fit others. These words just didn’t fit me.

Later at the end of the summer, I had a nervous breakdown and was admitted to an outpatient program at Hennepin Healthcare. It was determined that I had bipolar I disorder, complex PTSD, schizoaffective disorder, and an illness I was too embarrassed to ever tell anyone, borderline personality disorder. I wanted to get a book about BPD to learn more about it. In the review section, reviewers told potential buyers to stay away from people with BPD. They said these kinds of people were “terrible.” So I never mentioned it to anyone. I didn’t buy the book either.

After the program was completed, I was told I couldn’t go back to work for at least a year. Three months later I was granted disability.

A Place in the World, Self-Portrait, 2013

Age 42. At this point of time, I was on disability for five years. I felt awful. I kept thinking about how my friends had jobs and how hard they were working. I felt ashamed that I couldn’t work. I’ve worked all my life since the age of 14. My first job was at Woolworth’s in Dayton, Ohio in 1985. I was so excited to be working at Woolworth’s, just thrilled.

Here, I was still struggling to find my place in the world, my expression. The shirt I bought at Pride many years earlier should have been a clue. And yet, I persisted to pass as cisgender.

Beautiful Boi saw this photo once, and they said my nose was cute. Astonished, I felt myself blush. I’ve always had a complex about my nose. Some pretty little girl in first grade angrily said my nose was as big as the eight-foot folding table we were sitting at. I had a crush on her.

I did begin writing a screenplay that year. It was the first time I was creative in nearly ten years. I saw a creative coach, a dear friend of mine. She gave me the direction I needed, and this direction is another big part of the reason I am where I am today.

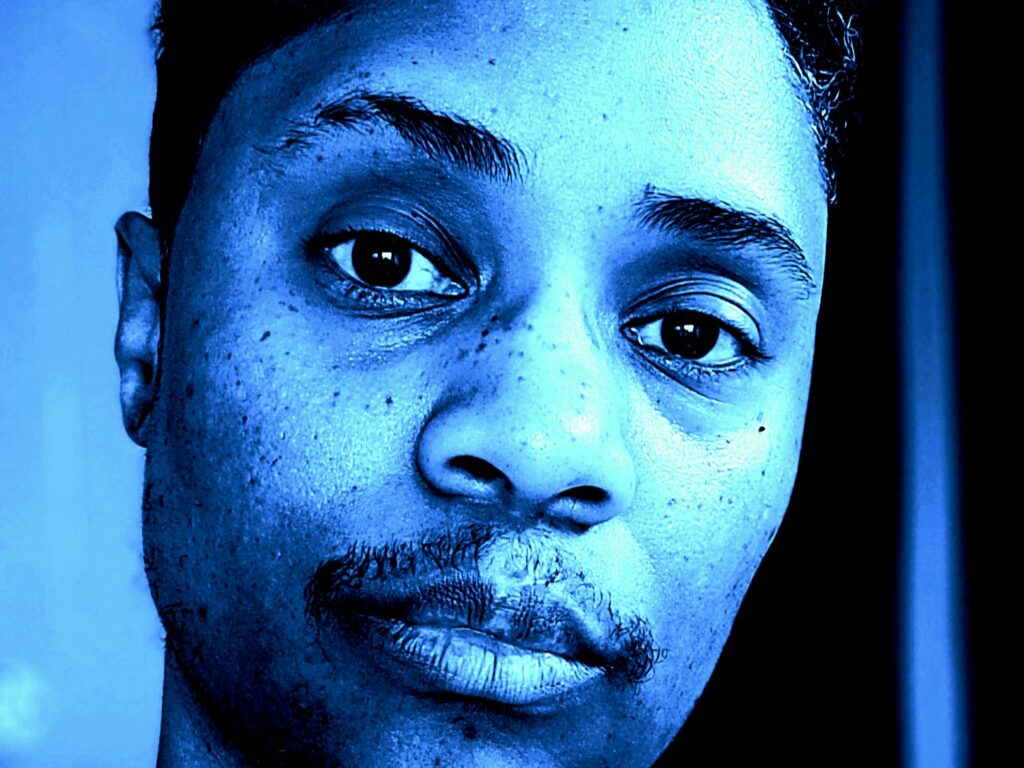

Transfiguration, Self-Portrait, July 2021

Age 50. This picture was the beginning of the new me as trans-identified. I am on testerone for eight weeks here. I am starting to feel more like myself. I understand the person I see in the mirror now, and I feel like home within myself. I am rescuing myself now.

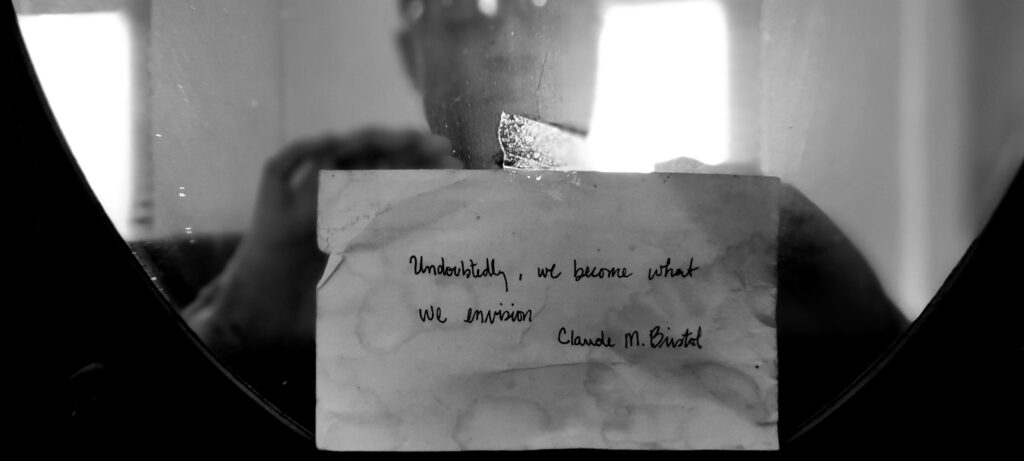

Kryptonite_Phoenix, Self-Portrait, 2021

This is me today. Sure. Confident. I am certain of a better future. More than that, I am excited. I am aware of my current thoughts without forgetting about my past. I am loving my past lives. I thank them for bringing me here today. I am working on forgiving myself. I am working on spiritual abundance. I am doing the sacred work of being unapologetically human. This work takes time and willingness to be curious. It takes radical acceptance. It takes love.

In my new trauma therapy, AIR Network Therapy, my new therapist and I went over my past diagnoses with the DSM manual. As we went through the criteria, it was determined that I didn’t have schizoaffective disorder, and I didn’t have borderline personality disorder anymore. The work I did in DBT helped me tremendously to overcome BPD. And I actually never had schizoaffective disorder. I have complex trauma (CPTSD.) With some of the emergency visits I had, some doctors only saw me for 20 minutes or less. In their records they made decisions about my mental health and labeled them according to those short visits. African Americans are often disproportionately misdiagnosed.

Mental health illnesses are on a spectrum. They are not death sentences. They are not absolutes. A similar diagnosis looks different for each person who has it. Our silence, in America, surrounding mental health is literally killing thousands of vulnerable people every day. I will not be silent; I am not ashamed.

The person, in this photo, was the one I saw in many of my dreams. This is the person Beautiful Boi saw. The person they told me I was all along. The person they never doubted me to become, because I already was. I just hid from myself in one of those rooms in my mind. Beautiful Boi found me. When I lost them, I had to do the work to find myself.

The day after my high school graduation, when I discovered my mother had stolen money from me, and after supporting her for close to seven months, with both fulltime and part time jobs—while going to high school—she kicked me out of the house. She told me my father’s alimony was coming soon. She said she didn’t need me anymore. We fought. A fight she started. A fight I tried to defend myself from as I was being choked. My friend, who was a witness to this fight, asked her parents if I could stay with them until I went to college in a few months. After years of physical, emotional, sexual, and now financial, abuse—jettisoned. I was deemed worthless, easily replaced by paper checks. Three months later, I arrived at Columbus College of Art and Design in Columbus, Ohio. I was dropped off by three people I would never see again. For the first time in my life, I was truly alone. Abandoned, I had no one.

28 years later, I would meet Beautiful Boi. I learned a lot about them. I learned so much from them. I still do. I miss them. I see them in my dreams. I hope they are learning more about themselves and thriving in their own way. Some people come into your life for three minutes, three months, three years, three lifetimes. Their happiness is important to me even if I can’t be a part of it. In the last 18 months, I had to learn to let every relationship take its own shape in its own time. Uncertainty is something I am leaning into. I am trying to find comfort and positivity in a future that is so beautifully and eternally unknown to me.

I am glad to be farther from it—the self-destructive behaviors; the confabulated beliefs. Loving yourself daily is hard work, but the rewards are worth the arduous process of alchemy. Forgiving yourself isn’t easy, but necessary. Now, every time I look in the mirror, I am completely present with myself. I look into my eyes, and not just the irises. I stare directly into my pupils and become one with myself. I can hold that gaze for moments. I more than accept and love this person, I like this person a lot. I see this person trying to be a good human, an honest human. I am proud of this person and all the people they have been before this very moment.

Creating this documentary will give me the powerful opportunity to fully examine my transition, my life, and what it truly means to be who I am spiritually, sexually, emotionally, and physically. I hope to find a peace of mind and a deeper appreciation for my existence. I hope someone finds value in my story. What started as a private video journal to give to Beautiful Boi has become an important self-portrait to give to audiences worldwide. All are welcome to watch it. Maybe they will see pieces of themselves glimmer upon the screen.

I will be back in several months to share more about the process and progress of the making of Beautiful Boi. My hope is that you will join me as I embark on this journey of transfiguration, power, and truth. I will share footage, photos, and essays about my process and insights. Please, be sure to check back in. Thank you for reading this.

Take care and be well,

Atlas O Phoenix

Please listen to Q Lazzarus’s “Goodbye Horses” as an accompaniment to this essay.

This song was featured in the film Silence of the Lambs. It was used during the scene where Buffalo Bill, a mentally disabled trans woman, dances to prepare for her destiny. She is lonely, yet optimistic and hopeful, though the film would have you believe she is a terrifying freak show. This film provided a grossly inappropriate account of disabled trans identity without making an attempt to understand it. Transness was used as a gimmick and plot point in this film. Offering this song to you is my way of reclaiming the true meaning and power of this optimistic song as a trans-identified person. As the song makes it clear: never let anyone predict your future based on their own failures. Enjoy.

For your convenience, it is linked to both Spotify and YouTube.

For more information, please visit www.beautifulboi.com, or @beautiful_boi_atlas_phoenix and @trans_late_MPLS on Instagram.