Before the Big Show: the week in dance

This week Lightsey Darst sits in on a TU Dance rehearsal, a fly on the wall as the dancers and choreographer Uri Sands prepare for the company's fall concert at the O'Shaughnessy, November 16-18.

TU DANCE CENTER, ST PAUL. FRIDAY MORNING, 11/9/12: Dancers are lying about, standing, stretching, kicking out the morning’s work before TU Dance company rehearsal. Some trace duets, marking their points of contact with each other. Their show opens in a week at the O’Shaughnessy, but you wouldn’t know it: They have the low-key buzz of chai, not coffee. A few chat off to one side. Lucas Melsha, in a “Legally Gay” t-shirt, says something about a “negative space splat.” Tall, he leans in a classic contrapposto on very ballet legs: long lean thighs, low knees, big calves.

“Is it whirlwind or worldwind?” Duncan Schultz wants to know. “Whirlwind,” says Yusha-Marie Sorzano. She looks like she could make one: spare, athletic, her hair scraped up in an efficient knot.

Choreographer Uri Sands gathers them for a quick huddle, orientation to the rehearsal. “And don’t ask no questions,” he finishes. They all laugh. They start with a piece that’s still in progress. Hunched over, creaking forward with a bundle of canes in each hand, Katelyn Skelley looks like something out of The Dark Crystal. Berit Ahlgren huddles in the cage of canes; Schultz runs from the downstage corner and back, maybe trying to reach her; and five or six other dancers form a flock, or line between. Sands wants to work on this line—how it moves, how it reacts to Skelley. He watches them run through a bit of it. “It’s the in-between,” he says. “More appendage-like.”

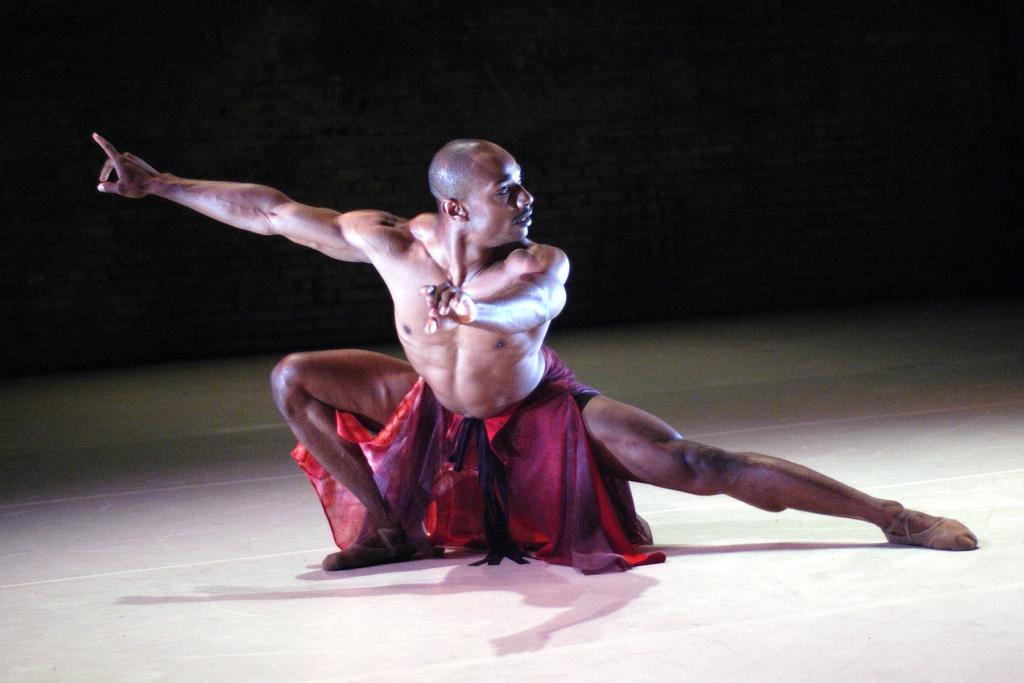

There’s something in common about how Sands’ dancers move—a balletic looseness in the legs that translates to more than the legs, modern-ballet splayed shoulders, flat ribs, the dropped-down hips of modern dancers. I don’t remember seeing such a pronounced style last time I watched TU, but I saw it when Alanna Morris danced her solo Dreams at this year’s Sage Awards: she’s changed. And it’s not just her shorn hair: Morris looks less, now, like anyone you’ve met before, and she dances less like it too. They all do. Even dark horse Elayna Waxse, a recent addition to the company (previously of Minnesota Dance Theatre), is letting her ballet shift to show something else—something at once new and elemental.

But it’s still not enough for Sands: he wants more. He talks to the dancers constantly, almost cajoling. “We’re just playing, we’re just playing,” he rushes. “One more time.” He doesn’t seem to want them to get fixed on anything yet. He’s right: They’re better when they don’t think they know what they’re doing. They’re explorers, not executants. This impression of process is so strong it half-overrides gender. You don’t get “men” and “women” from this company, no performed selves. “Just searching. Everybody all right? You look good.”

“It’s the simple things.” He sheds his shoes, his jacket. He goes at the choreography from a dancer’s perspective. What’s he after? Not a stage picture, exactly, and not purely a mood; it’s as if he’s feeling for the low pressure center that will spin the right storm. “Rest, rest.” He’s trying to get it creaturely, dark matter in motion.

Sorzano has a question. It doesn’t compute with Sands. “I’m trying to figure out the amount of negative space,” she clarifies. These are smart dancers; these dancers are thinking about what they’re up to. And—I want to say this in a way that’s positive, because that’s what I mean—these are dance students, too. They want to figure it out more than they want to sell it.

______________________________________________________

These are smart dancers; these dancers are thinking about what they’re up to. And these are dance students, too. They want to figure it out more than they want to sell it.

______________________________________________________

Case in point: Sands is trying to get an echo between Skelley’s bundles of canes and the limbs of the dancers—difficult because canes and bodies are not built the same way. “I just want to show the idea of the relationship,” he says. And the dancers are game. They pursue the integrity of the physical challenge, throwing their multi-directional training (modern, ballet, African, Gaga, whatever) into the mix. “Can you think a new thought with your hip?” When Sands says,“Rest,” no one does; they keep trying to work it out.

Skelley sprawls on the floor and her canes scatter, a bundle of loose nerves. Sands watches. He’s incurably restless: He needs something to play with. He takes one dancer’s yoga bolster, drums on it for a minute, discards it, then picks up someone else’s watch cap, stretching it, tossing it, putting it on one hand as if his hand were a head. The dancers don’t blink. I get the feeling rehearsal ends with everyone chasing down their strewn belongings.

“I need a recovery from this splay place,” Sands says. He drops and tries it out. Cold, he still has more meaningful extension than most, more ability to be wholly that movement in that moment. The dancers get themselves into insoluble situations—Waxse trying to find more up when she’s already on her head with her legs in the air. It’s dance twister. They laugh at themselves. Sands watches. “I’m still not convinced of us getting up. And it’s partly me, partly you. You’re missing something that I haven’t given you yet, or that you haven’t discovered.”

Their process reminds me of contact improv: There’s that same emphasis on organic progress, on finding the real connection between one part of the body and another, one shape and another. But this hunt for physical motivation occurs in a high-tension classical aesthetic, with limbs defined and separated against each other, cutting light and space. And where contact improv often allows the mind’s irony in, allows breaches of form and acknowledgements of human limits, this dance seeks another order entirely: the human transformed.

“Settle yourselves, settle yourselves. . . You’ve got to find her, you’ve got to find what she’s doing. If she’s not abrupt, you’re not abrupt.” Sands walks around. He doesn’t tell them what steps to use; he relies on their training to generate new forms.

Skelley tries to level herself up from the floor with her canes. The canes slip out from under her; her shoulders strain, her neck tenses. She looks like she’s hurt, like she almost can’t get up. It’s the most real struggle anyone’s put out so far, and Sands watches approvingly, talking her through it while everyone else looks on. When she’s done, he tries to echo her. “That’s lame,” he says to himself.

Everyone goes through it again. Then something clicks. “That works!” Sands exclaims. “What’d you just do? Can you go again?” It’s Melsha; he’s flipped from thinking of a single point that echoes the cane to a horizontal plane that levers up. “I like,” Sands says.

They all try it, Sands coaching. “You have to prolong that experience, you have to prolong that moment,” he murmurs. When they get it right, they don’t look like dancers performing steps; they look like roof tiles peeled up in a storm.

One moment down. Sands and company move on.

______________________________________________________

Related event information:

TU Dance will present their fall concert at the O’Shaughnessy, at St. Catherine University in St. Paul, November 16, 17 & 18. Visit the company’s website for more information on this and future perfomances:www.tudance.org.

______________________________________________________

About the author: Originally from Tallahassee, Lightsey Darst is a poet, dance writer, and adjunct instructor at various Twin Cities colleges. Her manuscript Find the Girl was recently published by Coffee House; she has also been awarded a 2007 NEA Fellowship. She writes a weekly column on dance for mnartists.org.