Art Review: “Token Male'”

Michael Fallon went to Soo VAC and took in "Token Male," a show of photography, sculpture, drawings and more by seven male artists. It runs through Oct. 26 at 2640 Lyndale Av. S. Phone 612-871-2263.

In my book, it’s a wholly good sign that an art show called “Token Male,” currently running at the Soo Visual Art Center in Minneapolis, has almost nothing to do with what the title suggests. That is to say, other than the fact that the artists are all male, the show itself ignores male issues. This means nada about male sexuality or gender identity, about attendant theoretical dogma about the male paradigm or male hegemony, or about anything else a typical women’s-studies professor might find fascinating (although no one else in the world does). Is this a sign that I can breathe easy again, and stop fretting, every time I step into a gallery, that I’m going to pummeled about the head with the same old tired programmatic and dogmatic and uninteresting identity art of the politically correct era? Does this mean that artists maybe have gotten over themselves at long last? That maybe they have begun to turn their gaze upward a little bit, away from the spot right around the navel (and directly below) that has for so long fascinated them? That maybe, just maybe, they are back in the business of making art that observes the world, that speaks of the beauty or ugliness of what is known and seen, that speculates about the nature of things that are unseen and unknown, or that is simply interesting to look at?

I was in my art-critical infancy when identity art emerged full-blown in the notorious 1993 Whitney Biennial, so I’ve had to deal with a lot of it through the years–performance artists whose acts are not much more than self-stimulation; image-makers whose work literally depicts “I am a (fill in the blank) man/woman,” and lots of other empty sentiment. If I sound bitter, I apologize, but I think my antipathy to this sort of work has justification beyond the fact that I have a lot of baggage from ten-plus years of the same-old-same-old. That is, aside from the fact that identity art is, as a general rule, uninteresting to look at (with a few exceptions–Kara Walker’s work, for instance, is strangely beautiful), the problem is that no matter if you’re male or female, a minority or a sexual deviant, a recovering addict or Catholic or victim of verbal abuse from your fourth-grade teacher, there’s only so much identifying you can do with someone else’s identity. That is to say, if everyone is shouting out what their identity is, and how downtrodden, abused, and mistreated they’ve been because of their identity, then who’s left to care? The fact of the matter is, everyone has their own mixed up marble-bag of identity issues; it’s so obvious a point that it means nothing–so why even bother to hold it up in front of each other in the first place? There is no other purpose for identity art than to stroke the artist’s own sense of self, and to make other people feel flaccid for not being just like the artist.

So my sincerest and most gratified thanks go out to the artists of “Token Male.” This show is not about any of these things–not even in an ironic way. Instead, it seems to be more about observations of incidental moments and stray thoughts, the trifles of life, anything that is insignificant, banal, tacky. The materials employed reinforce this impression: You’ll see Plexiglas here, and lime-green photocopier paper; plastic flowers and dried grasshoppers; neon-green Contac paper, graph paper marked with ballpoint pen, blobs of dried colored clay, and so on. I’m thinking maybe this says something about the zeitgeist–celebrating the beauty of the mundane in a post 9/11 world, or something along those lines–but I’ll leave figuring that out to deeper minds than mine. Instead, I’ll just revel in my profound relief that my dread about this show on hearing the title was unfounded.

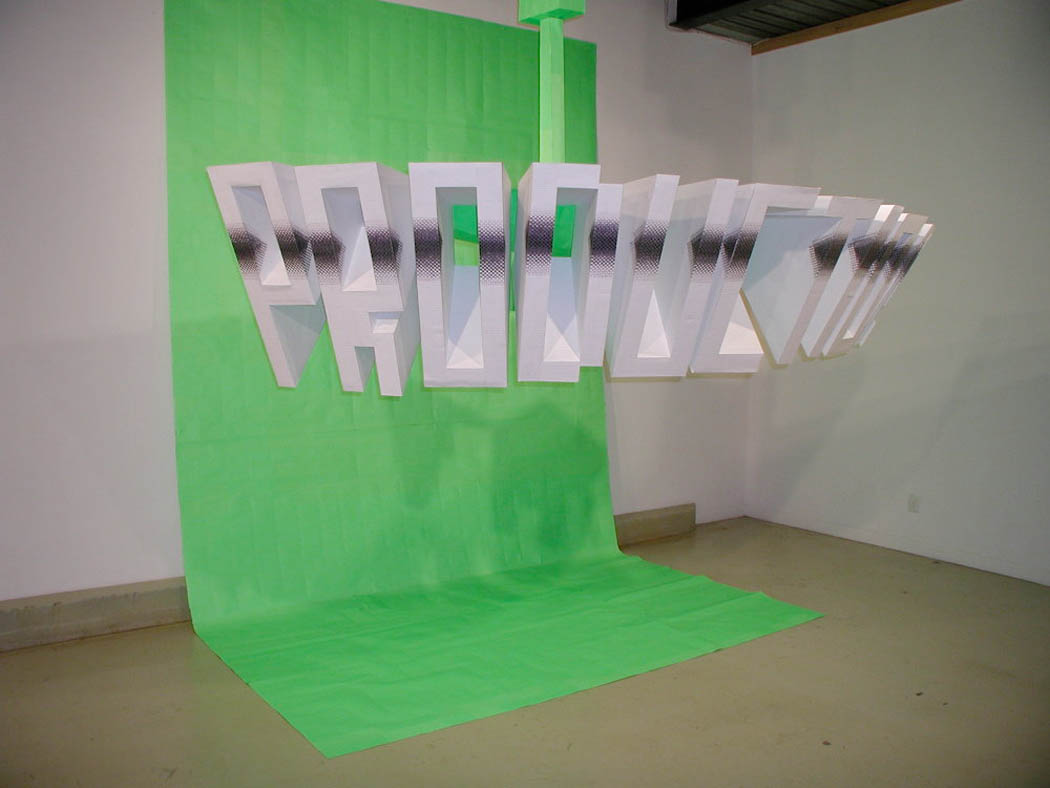

This is not to say the work doesn’t amount to anything–just that the work is informed by and defined by its casualness and its celebration of the decidely unprofound. Foremost among the works here are J. J. Peet’s. “Video Drawing” is a sprawling wall work of various bits and scraps of paper that looks something like an animator’s storyboard for an episode in progress. The small scribbled images of machinery, video cameras and tapes, strange text snippets, a small bird statue, and various unidentifiable items is cryptic and intriguing. Nearby, the installation “Video (untitled)” involves a video surveillance camera made from card stock, two metal bird statues (perhaps the same as in the storyboard) that could have come from the set of the “Maltese Falcon,” and a large three-dimensional block-letter title, “Productions,” made of graph paper and set before a vicious green paper backdrop. Likely, Peet has something to say about the meaning (or meaninglessness) of our media-mitigated world, and maybe something about the culture of surveillance. It’d take a long time to figure out exactly what he has to say, but I’m okay with that–I’m pretty relaxed about letting the work hint and rustle, letting it casually show me its bits of significance.

Other works here are less intriguing, but seem intent on keeping with the sagging-upholstery spirit of the show. Don Myhre’s “Shultzy” employs a found portrait of a middle-class patrician in some sort of bellboy uniform, with a belljar of grasshoppers jutting out from the painting’s surface. Okay. Meanwhile, Nathan Hylden’s untitled watercolors are minimalist monochromatic small paintings on paper of geometric shapes that evoke the shadowy sides of simple architectural spaces. These are unfortunately fairly easy to dismiss, as is John Vogt’s work, which employs Plexiglas sheets studded with words, “Where Eagles Dare,” or painted to look like an ocean of milk (with a sinking white battleship). It’s maybe something to do with a staid look at male militarism, or something completely different, but no matter–it’s not very interesting either way.

Perhaps the most ambitious piece is Thomas Rose and Scott Penkava’s installation “School Stories / Bad Behavior.” Ostensibly intended to evoke the far-off school experiences of boys who are now men, this work involves video, voiceovers, mounted inkjet prints of chalkboards, and dozens of lime-green paper airplanes scattered about the floor of the small room at Soo VAC built for such installations. While quite a sustained and realized production, the whole comes across as fairly obvious–a young man in a video runs around with scissors, for example, or sticks pencils in his nose and ears. And the voiceover of a guy prattling on about early sexual experiences reminded me unfortunately of the weisenheimer voiceover from “The Wonder Years.” But that’s the thing: given a fair chance, you just never know what art is going to strike your fancy and what’s not. At least none of the work excluded me from the possibility of liking it.