An Un/Education

As part of Mn Artists Presents: CarryOn Homes, a multidisciplinary program reimagining the museum as experimental classroom, writer and scholar Christina Schmid unpacks the deep structures that give rise to how knowing, learning, and teaching unfold in various cultural contexts, and suggests how we might reach beyond the model of mastery in order to embrace listening and the possibility of not knowing.

This is how the story goes: When Abu Hamid Al-Ghazali concluded his studies in Nishapur, he loaded his hand-written notes and books on a donkey’s back and joined a caravan to head home. Bandits ambushed the caravan and proceeded to rob the travelers of their valuables. Al-Ghazali begged them to spare his most precious possessions: the fruits of his long education. Eagerly, the bandits opened the donkey’s bags. When they found only papers and pages covered in writing, their leader said to the scholar: “All of your knowledge fits on the back of a donkey? Maybe you should consider pursuing a different kind of knowledge.” Until the end of his life, Al-Ghazali recounted this incident as the best advice on education he ever got.1

“Classrooms can be anywhere and teachers can come in all forms,” write the five artists who make up the collective CarryOn Homes: Zoe Cinel, Preston Drum, Aki Shibata, Peng Wu, and Shun Jie Yong. The five started collaborating in 2018, when they turned the Commons Park in downtown Minneapolis into a temporary platform for gatherings and sharing stories among the many immigrant communities who call the Twin Cities home. For August’s iteration of Mn Artists Presents, a series that turns the Walker Art Center’s hallways and passageways into sites for curatorial interventions, CarryOn Homes engages the question of education: who teaches whom, how, when, where, and why? What is considered a worthwhile pursuit of knowledge in the United States and in other parts of the world?

Over spring and summer of 2019, members of CarryOn Homes began exploring the subject in depth in a series of interviews with immigrant artists. In their practice, interactions and encounters with people generally matter more to them than formal considerations. What emerged from the growing archive of conversations were questions about power, epistemology, and marginalized ways of knowing. Eventually, CarryOn Homes invited four artists to produce one-night performances at the Walker Art Center: Valerie Oliveiro, who grew up in Singapore; Tou SaiK Lee, who describes himself an intergenerational bridge-builder in Minnesota’s Hmong community;2 Pedram Baldari and Nooshin Hakim Javadi, who studied in Tehran before pursuing graduate degrees in the United States. What all four share is a keen sense of how “the roles of knowledge production, knowledge hierarchies, and knowledge institutions” are far from neutral, as Linda Tuiwai Smith argues, but always “the site of significant struggle between the interests and ways of knowing of the West and the interests and ways of resisting of the Other.”3

Education, as a practice of sharing knowledge, is intimately entangled with these political, institutional, and philosophical concerns of knowledge production and distribution. Who is hailed as a potential knower, who as an object to be studied and known? What constitutes knowledge? Which histories churn underneath polite institutional veneers? Revealing the deep structures that give rise to how knowing, learning, and teaching unfold in a specific cultural context is central to CarryOn Homes’ curatorial vision. Oliveiro, SaiK Lee, Hakim Javadi, and Baldari all have experience in educational systems that originate outside of the United States, systems that come with their own set of promises and problems.4

The artists’ respective experiences with more than one educational model allow for moments of disorientation that render the educational paths typically taken for granted acutely strange. Fellow immigrant Sara Ahmed captures the subsequent re-orientation: “Such moments do not always present themselves as life choices available to consciousness. At times, we don’t know that we have followed a path, or that the line we have taken is a line that clears our way only by marking out spaces we don’t inhabit. Our investments in specific routes can be hidden from view, as they are the point from which we view the world that surrounds us. We can get directed by losing our sense of this direction. … After all, it is often loss that generates a new direction.”5 As first- and second-generation immigrants, the four artists are intimately familiar with loss—of bearings, homes, certainties. Yet, in their work such loss is reconfigured into a unique sensibility and sense of the institutional and political armatures that direct how bodies move through the world. What CarryOn Homes and their collaborators set out to do in the Walker’s hallways, lobbies, and passages is, first, to make these structures of authority palpable.

In this way, the artists’ interventions could be seen to participate in the long history of institutional critique: a politicized art practice that for decades has aimed at unmasking the power relations and structures in the field of art. Site-specific and impermanent, CarryOn Homes’ re-envisioning of the museum as an experimental classroom offers room for critique but leaves the institutional hierarchies unscathed: Galleries remain off limits and reserved for exhibitions curated by professional experts, while local artists-turned-curators host one-nighters in the hallways. Charting the generations of institutional critique, Hito Steyerl observes that “if during the first wave of institutional critique, criticism produced integration into the institution, the second one only achieved integration of representation:”6 according to Steyerl, twin commitments to more diversity and less homogeneity risk reifying cultural identities in the service of the institution as “sacralized ethnopark” and serving as “an overall spectacle of ‘difference’” that unfolds “without effectuating much structural change.”Steyerl’s analysis ends with the third wave when “the question concerning the function of the institution of critique” becomes more complex still: “a deeply ambivalent subject…develops multiple strategies for dealing with its dislocation” while critical institutions struggle in the face of neoliberal institutional criticism.7

Without doubt, these earlier strands of institutionalized critique reverberate through CarryOn Homes’ curatorial initiative (and indeed, through past iterations of Mn Artists Presents).8 But the critically charged relationship between artist and institution has been shifting once again: at home in the precariat, the artists use the institution in a savvy though wary form of reciprocal opportunism. If the institution relies on immigrant and IPOC artists to perform its cosmopolitan-progressive woke-ness, the artists capitalize on the prestige of the institution to impress other authorities and demonstrate their achievement: the Department of Homeland Security, for instance, where artist visas and green card applications are granted or denied. In the hands of CarryOn Homes and their collaborators, then, exploring the question of education is fraught with questions of power within and beyond the art world, access to resources, and the requisite know-how to maneuver through disciplinary bureaucracies and make the most of them.

The artistic interventions that animate the Walker Art Center’s hallways fill these spaces of transit with alternative modalities of teaching: a sharing of knowledge that is light-footed and fleeting, “in but not of” the institution.9 It is a fugitive knowledge, not only vested in escape but “separate from settling.”10 Unsettled and unsettling, such knowledge resists the protocols of research, which is deeply suspect, in Tuhiwai Smith’s words, “as a set of ideas, practices and privileges that were embedded in imperial expansionism and colonization and institutionalized in academic disciplines, schools, curricula, universities and power.”11 The challenge, then, is to imagine other forms of sharing and producing knowledge, to move beyond the model of critique and to speculate with abandon: “We cannot say,” writes Jack Halberstam, “what new structures will replace the ones we live with yet, because once we have torn shit down, we will inevitably see more and see differently and feel a new sense of wanting and being and becoming.”12 Or, as Tuhiwai Smith puts it, “the intellectual project of decolonizing has to set out ways to proceed through a colonizing world. It needs a radical compassion that reaches out, that seeks collaboration, and that is open to possibilities that can only be imagined as other things fall into place.”13 To create an opportunity where other things may fall in and out of place, to reveal glimpses of what might come to be, is a second part of CarryOn Homes’ curatorial vision.

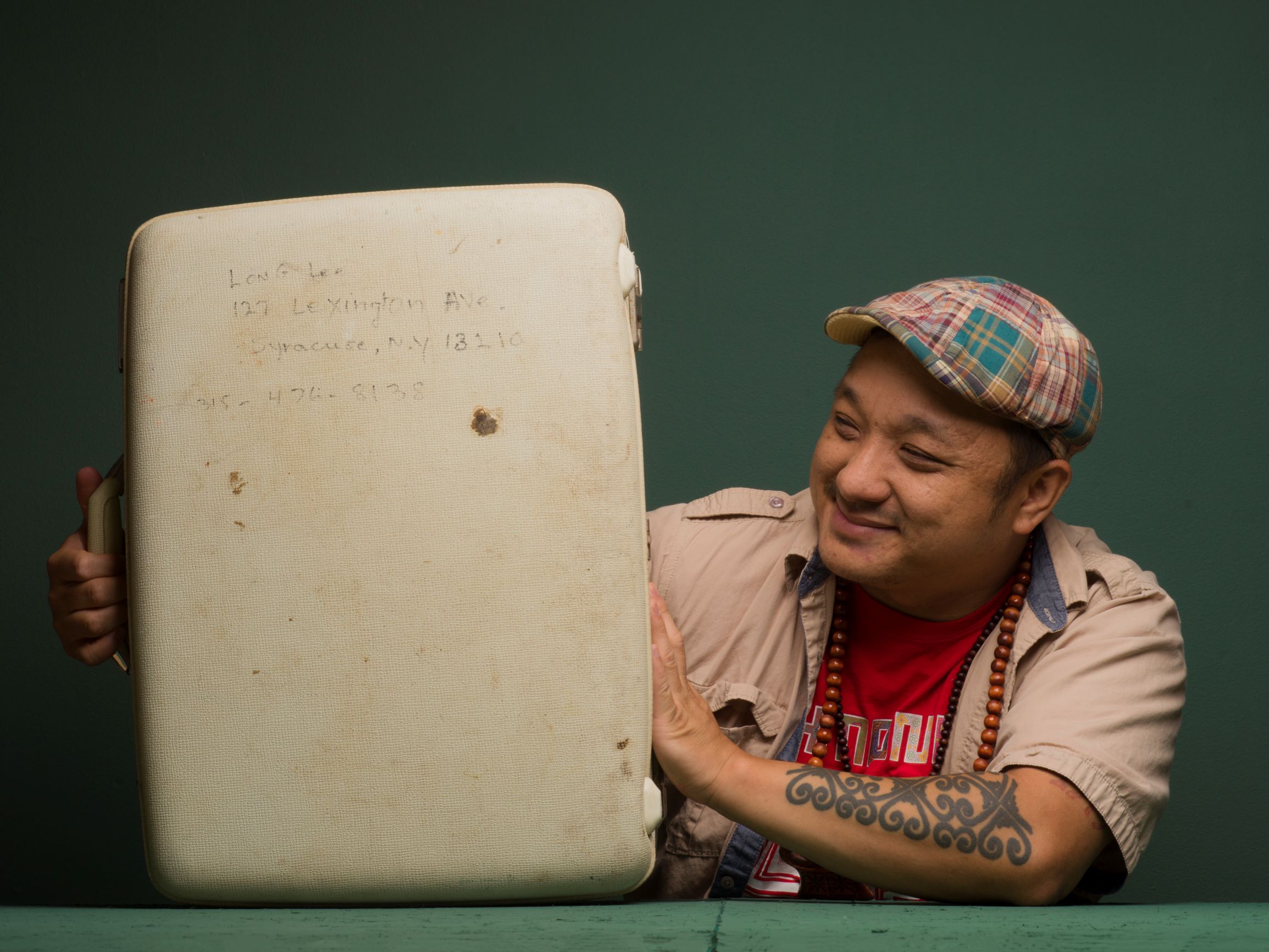

When Tou SaiK Lee brings Hmong elders to the Walker to share stories and play traditional instruments, the point is not only to perform lived cultural continuity but to open a space for a sharing of knowledge radically different from the hierarchies of expertise and explication: “the very act of storytelling, an act that presumes in its interlocutor an equality of intelligence rather than an inequality of knowledge, posits equality, just as the act of explication posits inequality,” argues Jacques Ranciere.14 Traditional storytelling coexists with contemporary forms of expression in SaiK Lee’s artistic practice: he blends hip hop and spoken word to voice distinctly Hmong experiences. At times, his poetry interprets ancient Hmong symbols whose ornate geometric patterns once held precise meanings. In the 21st century, they have come to represent Hmong culture: no longer stitched on fabric, they are inked onto bodies, tattooed as an inerasable inheritance.

Valerie Oliveiro, too, centers the body in her site-specific intervention that uses circles of light as compositional elements to engage with transitional spaces and the off-limits Walker galleries where artwork the institution considers of more permanent significance resides. Rather than treating illumination as a tool to make things appear “in their best light,” Oliveiro considers light an elemental force capable of undoing the pervasive Enlightenment metaphor: the light of reason that drives all other modes of understanding into the shadows. As bodies move in and out of the light, the artist wonders, what radiance do they absorb, what do they prove impervious to? In Oliveiro’s hands, light becomes a means to dwell in the interstices between spaces that already have been claimed by institutions, nation states, and other authorities.

Inspired by Al-Ghazali’s story of outlaws offering educational advice, Pedram Baldari and Nooshin Hakim Javadi invited a donkey to the Minneapolis Sculpture Garden, its saddle bags heavy with art history books. The donkey’s garden tours conjure another set of stories: the tales of Molla Nasreddin, a putatively wise man who is in constant conflict with his beast. The satires pit human folly against asinine stubbornness, never settling on where wisdom may be found—in man or beast. Inside the Walker, a short video by Baldari, A Physical Study of the Education of Art (2015), offers the most pointed criticism of the night: as a man drags a woman across the floor by her feet, she writes the phrase “I am the artist” in carefully executed white brush strokes, before, in one final pull, her brush erases the entire sentence. How do artists come to be? By being pushed and pulled? Or, does education happen entirely differently?

“The route students will take is unknown. But we know what they cannot escape: the exercise of their liberty. We know too that the master won’t have the right to stand anywhere else—only at the door. The students must see everything for themselves, compare and compare, and always respond to a three-part question: what do you see? What do you think about it? What do you make of it?”15 The image of a master who only stands at the door suggests a humility that is too often at odds with Western protocols of knowledge production and dissemination. Potawatomi botanist Robin Wall Kimmerer writes, “I smile when I hear my colleagues say ‘I discovered X.’ That’s kind of like Columbus claiming to have discovered America. It was here all along, it’s just that he didn’t know it. Experiments are not about discovery but about listening and translating the knowledge of other beings.”16 What becomes available to understanding when alternative attitudes re-frame how we go about learning about the world?

Reaching beyond the model of mastery, dominance, and subjection to authority while embracing the intimacy of listening may have profound consequences for “the beyond” of teaching: “What the beyond of teaching is really about is not finishing oneself, not passing, not completing; it’s about allowing subjectivity to be unlawfully overcome by others, a radical passion and passivity such that one becomes unfit for subjection.”17 Defying the imperative to pass, complete, overcome, discover, and dominate goes against the law of what it means to be a particular kind of knowing subject. But letting the “I” subside by giving in to passion and passivity might just produce an odd inaptitude: one is no longer fit for subjection, subjugation, suppression. (It bears remembering that Al-Ghazali’s impromptu teacher was a bandit, beyond the law, too.)

To end, a story that Alexis Pauline Gumbs tells in M Archive: “she wouldn’t tell us anything until we stopped knowing. stopped thinking that we knew, which came at the long edge of a lot of time spent acting like we knew. and then pretending to know what we didn’t know. and then pretending not to know that we didn’t know. she waited. she saw through all of it. at least fifteen times we thought we were ready. we thought we had let go of everything. we thought we were meditating right then in the midst of our thoughts. and she could hear it. every piece of held-onto knowledge clanging in our brains. every muscle memory of do right. so she waited through our impatience. our protest. our feigned indifference. she waited. and when it was over and all there was left was the sound of us not knowing nothing, then she began. and she said:

it all started when i stopped knowing. before that they wouldn’t tell me anything …18

This article was commissioned as part of Mn Artists Presents: CarryOn Homes.