Almost Too Familiar

Nathan Young looks closely at the new abstract paintings and installation by Shawn Kuruneru, parsing the tangle of novelty, theory and art historical homage that informs the work.

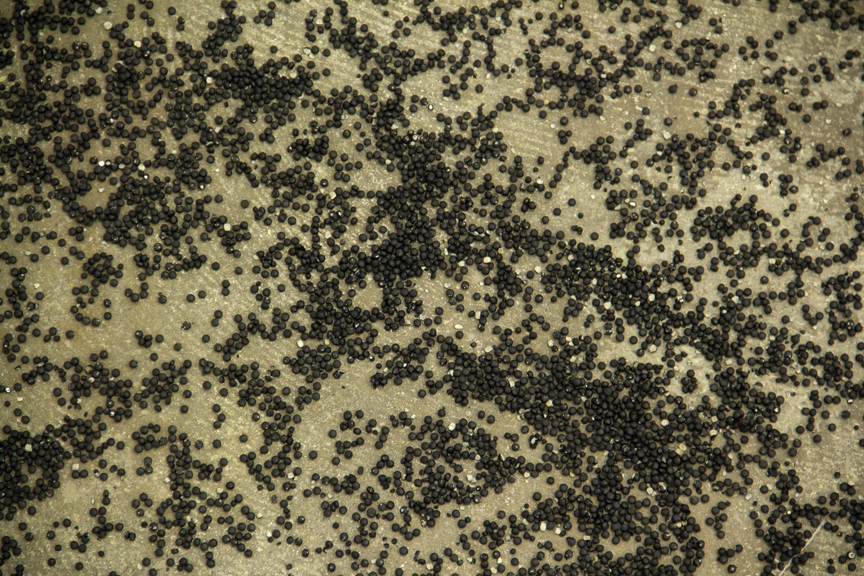

Shawn Kuruneru’s most recent exhibition, Landscapes, consists of eight paintings and one site-specific installation which curator David Petersen describes as a “floor drawing.” Such a view on the work encourages us see the black-dyed gypsum beads as if they were dots of ink delibly marking the gallery’s concrete floor. Untitled (Minneapolis) could just as well be sold as sculptural pointillism, or conceptual carpeting. What’s more, a focus on materiality and rhetoric surrounding the work encourages us to consider the value of determinate definitions. The possibilities there, Petersen reminds us, are endless.

Like the installation, Kuruneru’s paintings also entangle a viewer’s attempts to index his work into tidy categories — Lotus, for example, is not quite a painting, and not quite about lotuses. In his studio, the artist lays large, unprimed canvases, horizontally or on a slant, on which he then he bleeds and brushes black, blue, and red ink to create sumptuous abstractions. The materials here bond and become something new. In the back gallery, Kuruneru has three such works for which he’s scattered three shades of blue ink and acrylic on panel. The textures rhyme with that of the floor drawing, each capturing starscapes, movements of wind over grass, the look of a satellite image of shifting sands adjusting across dunes.

Similarities among artworks across time periods are often as evident as a family likeness, and the line between a novel theory and aesthetic redundancy in this work falls somewhere between historical awareness and personal taste. Kuruneru’s sophisticated monocolor-field abstraction is, no doubt, indebted to Morris Louis, Helen Frankenthaler, Jules Olistksi, Mark Rothko and Ad Reinhardt. From this popular history we could read Kuruneru’s recent work as statements of their styles; the questions that arise from Song, for example, point viewers toward a space of obscurity through which Kuruneru and Petersen offer little other guidance. Then again, their responsibility is not to give answers but to make conversations possible.

In fact, David Petersen is usually on-site at the gallery during open hours, and in the course of a conversation about the work, he might also point you in the direction of 11th-century China. Artist Li Huayi similarly engages with the shan shui style of the Song Dynasty but, rather than conceptualizing the act, Huayi maintains figurative and titular narratives that drive new interpretations of the familiar imagery. He could be judged as merely copying a Guo Xi landscape, but a more helpful reading might honor Huayi’s work as both homage and innovation. And Kuruneru and Huayi, each in their own way, harken back to a style that might otherwise, someday, somehow, be forgotten.

Lineages of a style, however cursorily drawn, outline the growth of artists’ appreciation for their predecessors in a way that can help track the differences between a novel approach to familiar themes, a boilerplate that’s easy to sell, and the kind of artwork that could stay stuck between traditions —something not quite new, but not quite usual either. For example, Robert Bain’s work might remind you of Oscar Murillo’s, which could remind you of Jean Michel Basquiat and Cy Twombly’s paintings. Kuruneru’s works here are not so much derivative, rather they line up together to articulate a particular style of art-making. Likewise, Broc Blegen’s 2012 Minnesota Artists Exhibition Program exhibition might feel familiar to Raymond Pettibon’s miniatures, or to the late Elaine Sturtevant’s project to “give visible action to dialectics”; in the early 1990’s Charles Ray made sculptures that still live somewhere in the “uncanny valley” just a few years before Tony Matelli, whose work may or may not have inspired Ron Mueck and John de Andrea, and some of Matelli’s other sculptures align with the way of craftsman-artists like Derrick Guild and Matthew Merkel Hess. That these artists walk along found paths should serve not to undermine the significance of that familiarity, but rather to support our appreciation for those artists’ origins and tributes.

Kuruneru’s Landscapes is a conceptually driven exhibition that offers quiet protests against the traditional uses of materials. The paintings are safe and familiar with both ancient and modernist styles, just different enough to provide a feeling of having discovered something special. When contemporary artworks begin to look a bit too familiar, however, the differences among various abstract paintings begin to function like the differences among various pieces of contemporary interior design. When we go to Lappin Lighting, most of us do not ask the owner for the history on 136 styles of desk lamps. Our next purchase will likely just come down to a well-priced model that fits with the room. If we were to critique art like we shop for lamps, then the next abstract painting you see would look only familiar.

______________________________________________________

Related exhibition information:

Shawn Kuruneru: Landscapes is on view at David Petersen Gallery in Minneapolis from June 20 to August 16, 2014.

Nathan Young works as the curator for United Theological Seminary in New Brighton, and a co-director with Wing Young Huie at the Third Place Gallery in South Minneapolis. Find him on Twitter: @nrp_y.