After the Party

Two years after the hard-won legalization of gay marriage, queer couples are just as respectable as their straight counterparts. Joe Sinness's painstaking drawings are filled with nostalgic affection for the wilder days of gay culture, but he's too smart an artist to stop there.

A crumpled pink beach towel lies in the corner. Covered in bits of sand and flanked by three spoilt napkins, it’s titled Stage and indeed sets the scene for Fey: Drawings by Joe Sinness. Recently back from a residency on Fire Island, the artist brings a little bit of beach into Macalester’s Law Warschaw Gallery. Far from a simple case of post-summer blues, Stage raises the specter of another aftermath: two decades after the lethal surge of the AIDS epidemic, Fire Island features prominently in popular accounts of gay history as a place of abandon, never-ending beach parties, and happy promiscuity. Then, the story goes, gay culture promised a true alternative to normative coupledom. Now, two years after the hard-won legalization of gay marriage, queer couples are just as respectable as their straight counterparts. Fey is filled with nostalgia for those wilder days, but Sinness is too smart an artist to stop there.

A recipient of the 2013 McKnight Fellowship, Sinness is no unknown, yet Fey is his first solo show in the Twin Cities. His medium of choice, colored pencils, has remained constant. His work still looks like a long labor of love in its intimacy, precision, and commitment to craft. But seeing his drawings installed with the same uncanny attention to detail is exciting: they chat and vamp, strike up conversations or choose to be more elusive, maybe even a little reclusive, at times.

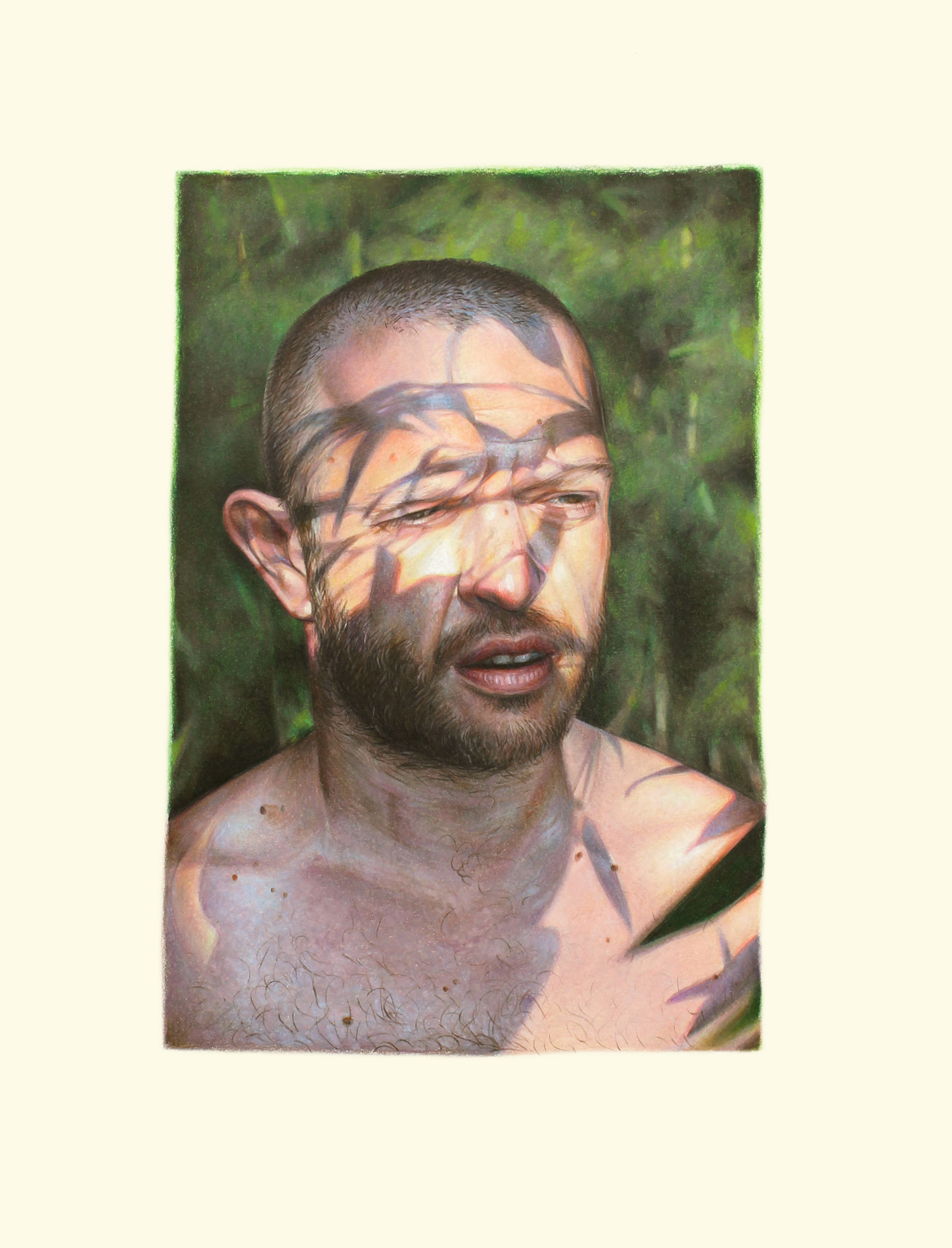

The work on view loosely falls into two groups. The Fire Island drawings, which include beach walkers and close-up portraits, are haunting in their exquisite vulnerability. Far from the seemingly inviolable, gym-chiseled bodies fetishized as the epitome of contemporary masculinity, the figures in the Beach Walker series are middle-aged. This is what survival looks like: a little pudgy around the waist, with slightly slumped shoulders that have known defeat. Affectionately, the drawings catch moments of humility. No raucous parties here but rather quiet contemplation, as these men stand and watch the surf. The portraits of Jesse, Peter, Keith, Liam, and Wes (all 2015) capture a similar honesty, as if the subjects were done pretending. For the moment, their faces are naked, unguarded. Their nakedness could not be more different from the one implied by the laconically titled Left Behind: a blue shirt hangs from a bare branch, a remnant of past gestures of undress.

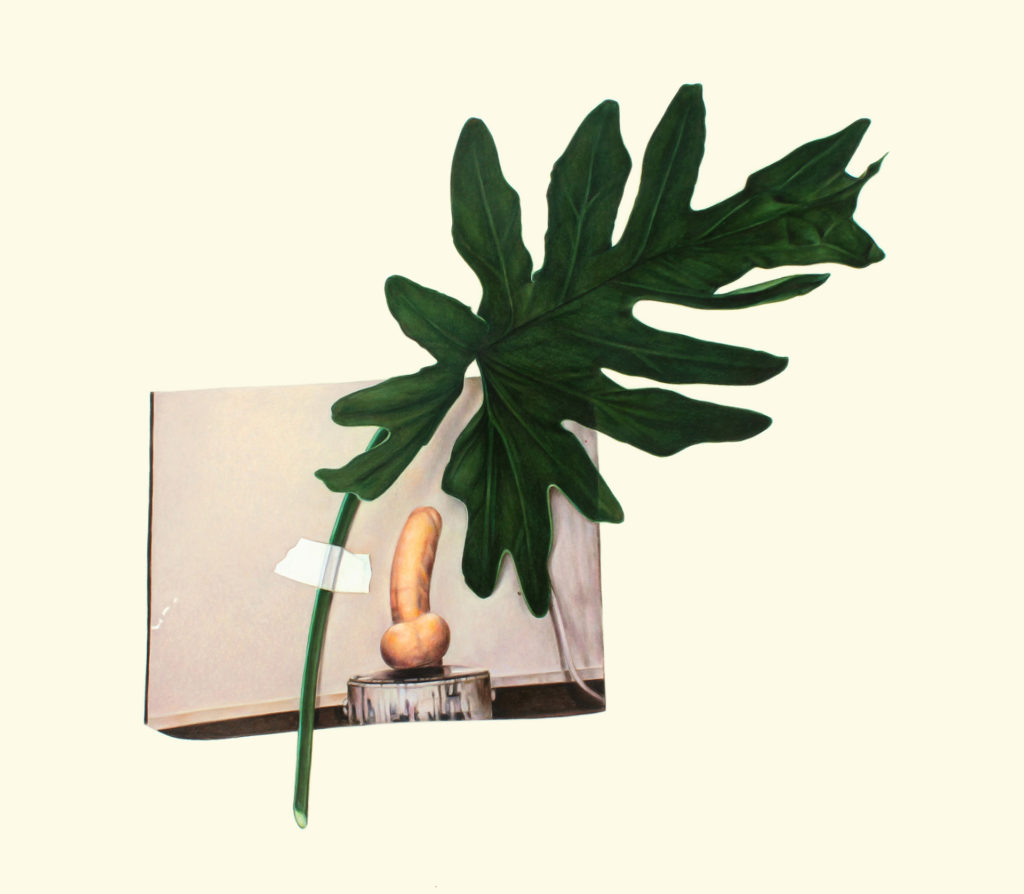

The tone changes in the drawings installed in the gallery’s larger space. Filled to the brim with campy humor, cheeky gestures, and raunchy puns, they assemble a cast of glamorous Hollywood icons, drag queens, porn stars, and pretty boys. The drawings delight in being very, very naughty and yet compel by their undeniable sincerity. A painting about painting (2015) shows an exotic leaf taped across a rectangular image of a sizeable dildo on top of a can of paint. The drawing manages to mock the phallic preponderance of so much art historical discourse on painting yet adorns the scene with handy houseplant foliage. Elsewhere, turquoise beads, shiny crystals, flowers, and ribbons serve as similar gestures of graphic reverence. Sinness has described these drawings as shrines, his homages to gay culture.

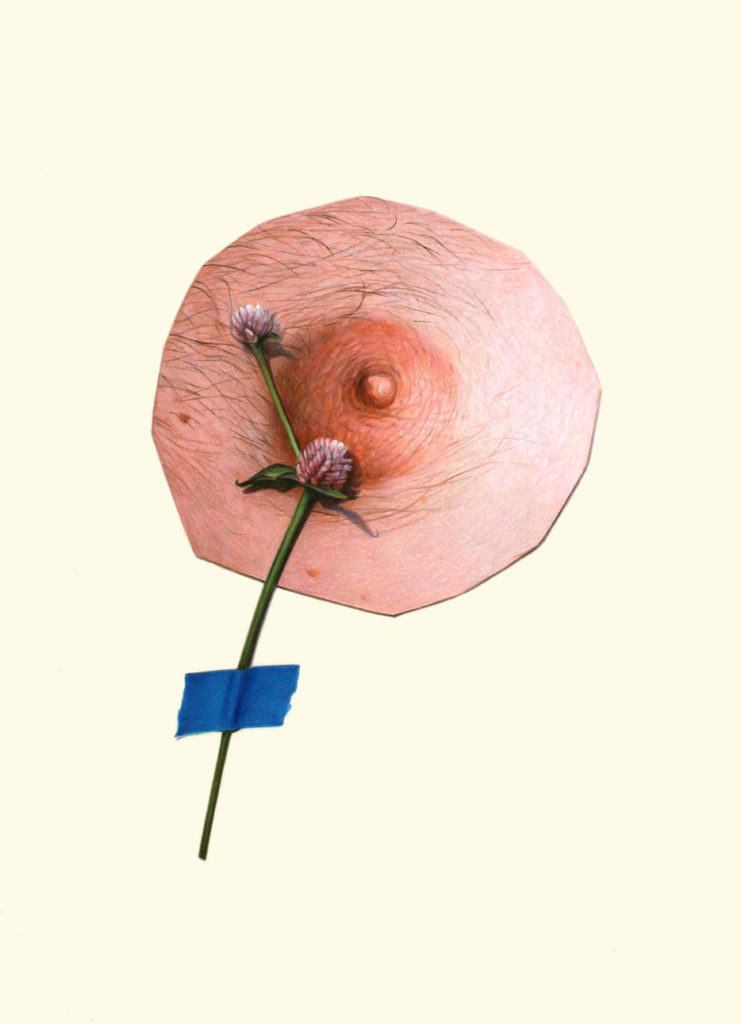

Nipple, 2015. Courtesy of the artist.

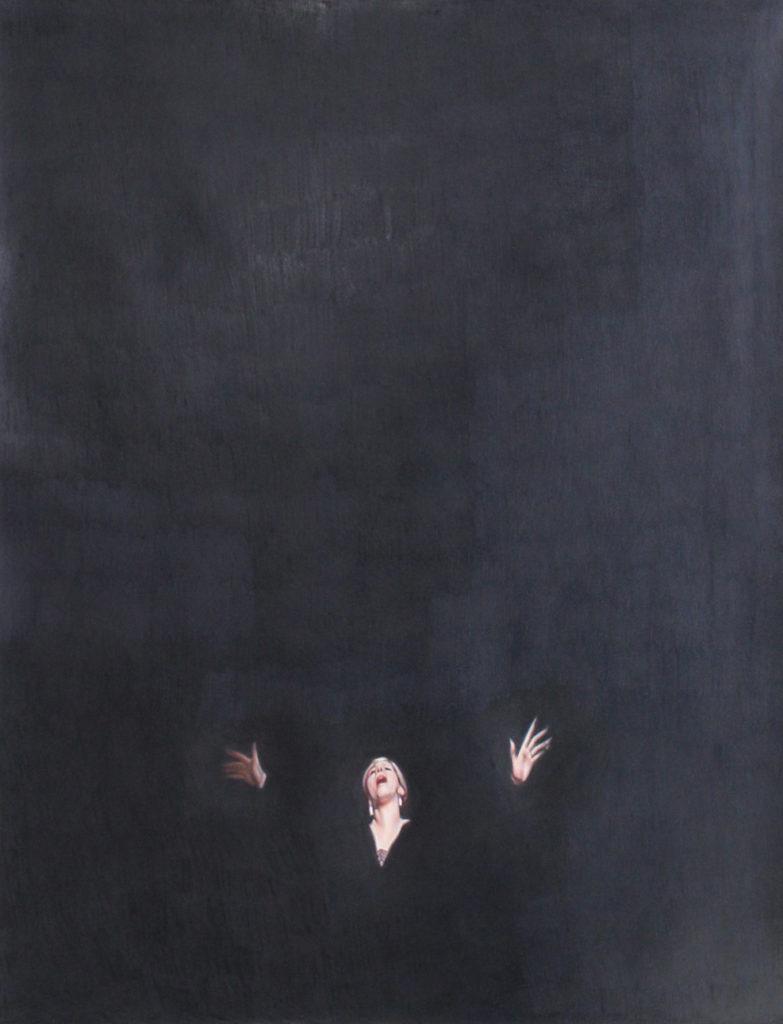

Rose’s turn, 2014. Courtesy of the artist.

Veil, 2014. Courtesy of the artist.

Given, 2014. Courtesy of the artist.

Frequently, the drawings masquerade as collages. In Amorous kisses (2015), blue tape seems to hold in place a single wilted tulip draped above a snapshot of a three-way French kiss. In Nipple (2015), Sinness draws the same blue tape fixing a sprig of clover to what only looks like a separate piece of paper complete with a drop shadow. A wrinkly plastic sheath protects a photograph of a ripped male torso in Veil (2014), while Rose’s turn (2014) features a sparkly piece of fabric pinned, mock-modestly, onto the unfolding ménage à trois. The dissimulations feign fragments when the drawings are whole, their surfaces smooth.

By exaggerating their constructed-ness, Sinness emphasizes the gaps and empty spaces between individual elements. Thus the drawings remain open-ended and loose, despite the precision of expert draftsmanship: in the cracks, unruly meanings sprout. Double entendre lives there. And of course gay culture has had to excel at reshuffling signifiers to communicate in clandestine symbolic codes. Far from simply sentimentalizing a more scandalous time, Sinness’s work pays tribute to a history of making do with what is given.

Given: (2014) raises that very question as a statement that calls for completion. The drawing directs the gaze through a duct-tape star that serves as a makeshift aperture, past potted plants, to an image in nocturnal hues. Held in place by the ubiquitous blue tape—the kind that leaves no sticky traces—the image-inside-the image shows a man’s bare back, blue and black shadows playing on his shoulders. Desire, distance, a hint of danger, and luminous darkness are givens.

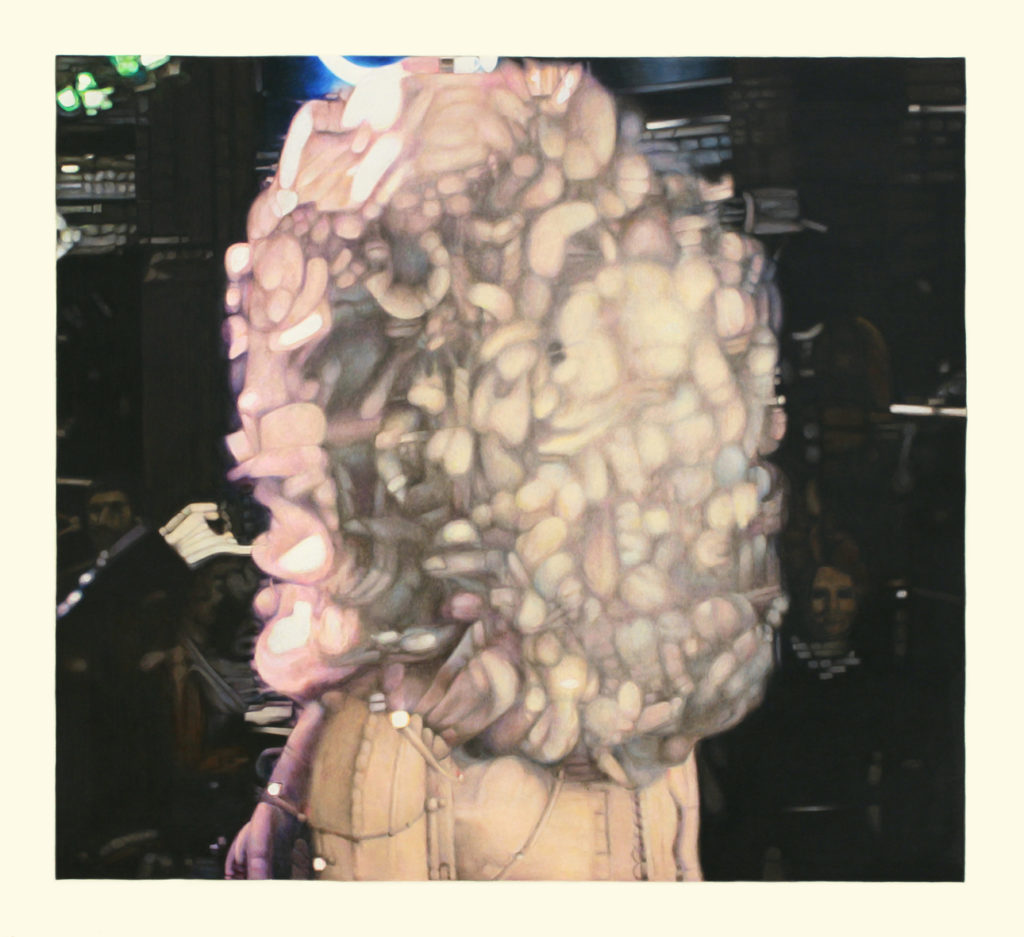

Evocative and touched by melancholy, darkness recurs elsewhere in Fey. In The world is bright, all right (2014), Barbra Streisand raises her hands to a black void. No stage lights illuminate this diva moment. In contrast, Sweet Agony (2015) shimmers with the otherworldly glow of Dolly Parton’s elaborate coiffure. But the star has passed (we see her from the back), and the drawing shimmers as if slightly out of focus. Liz Taylor’s appearance in It’s a familiar dance (2015) completes the trinity of gay icons. Divided into six vertical black and white strips, Sinness shows moments of her academy-award winning performance in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966). A huge departure from her earlier roles, playing middle-aged Martha shows Taylor sparring with her then husband, on and off screen. Polite masks shatter. What remains after the dinner party is over? In a show that celebrates desire and resilience in the aftermath of an epidemic that still is not over, the reference to this film is no coincidence.

So yes, Fey is fond of all the fun and games. Three spotted bananas peek out under a striped beach towel in a vertical diptych that includes Amorous Kisses. Yet Sinness also conjures another world: one where raunchy humor meets tenderness, where solitary male figures stand and watch waves break. What kinds of intimate encounters become possible when we meet Liam’s gaze and follow Jesse’s sidelong glance? Sinness does not answer the question. But he dares raise it.

Related exhibition information: Fey: Drawings by Joe Sinness is on view in the Law Warschaw Gallery at Macalester College, St. Paul, from September 25 – November 22, 2015. There is an artist talk in the gallery October 15 at 7 pm. See more work by the artist at http://joesinness.com/.