Remembrance of Things Past, Revived for the Present

27 years after its premiere, now that AIDS has receded in our cultural consciousness, gay marriage is legal, transgender actors, activists, and artists are cultural ambassadors for tolerance, and the first woman is running for U.S. President, what does Mark Morris's once groundbreaking "Dido and Aeneas" bring to an audience?

By the time the Mark Morris Dance Group premiered Dido and Aeneas in 1989 at Théâtre Royal de la Monnaie in Brussels, where the company was in residence, Morris had already caused considerable stir in the worlds of art, music and dance. Works like the sublime Drink to Me Only With Thine Eyes, the exhilarating L’Allegro, il Penseroso ed il Moderato, the fierce yet reverential Stabat Mater, and even Mythologies (inspired by theorist Roland Barthes’s essays collected in a book of the same name)—many of these dances were set to classical if not Baroque music—flew swiftly and decisively against modern and post-modern dance norms in impulse and instigation, approach and aesthetic.

Morris, without reservation, was choreographing dance to music. More accurately, he was merging music (after thoroughly studying the score with the intelligence, intuition, and dedication of a trained musicologist) with movement to create, in essence, a physical manifestation of the sounds, rhythms, themes and variations, tones, patterns, and lyrics he found in those scores. Some critics were not happy. He was accused of “music illustration,” of creating blow-by-blow pictures—through gesture and movement—of what was occurring in the music. This was seemingly a bad thing, as his work offered neither modern dance’s abstracted emotion, independent of music, nor post-modern dance’s insouciant re-conceptualization of vernacular movement and celebration of anti-virtuosity.

Morris’s seamless integration of movement and music, often compared in virtuosity and genius to the ballet choreography created by George Balanchine, nonetheless illuminated music in a way never seen before. “Mark’s works are so profoundly musical, and incredibly satisfying to perform,” dancer Peggy Baker told The Globe and Mail in 2013. Baker performed with and for Morris in the White Oak Dance Project, which Morris created with Mikhail Baryshnikov in 1990. “You feel like you become part of the fabric of the music itself.” To watch one of the aforementioned works, always set to live music, was to be admitted into a realm in which the dancing body became music, symbol, character, and emotion, in kinetic ways that resonated within one’s own body, and with our most basic, archetypal humanity.

With Dido and Aeneas, inspired by Henry Purcell’s 17th-century opera and Nahum Tate’s libretto (in turn based on Virgil’s myth), Morris, an openly gay choreographer, cast himself in the role of Dido. As he told New Yorker dance critic (and author of a biography of Morris) Joan Acocella, during an interview at the 2009 International Festival of Arts & Ideas, he was devastated by the loss of friends due to AIDS, experiencing anxiety around his own sexuality, and wanted to create what he thought might be his last dance. He divided the main part into two roles—Dido and the Sorceress who helps to engineer the Queen’s demise. Morris made those parts on other dancers, then learned the work himself.

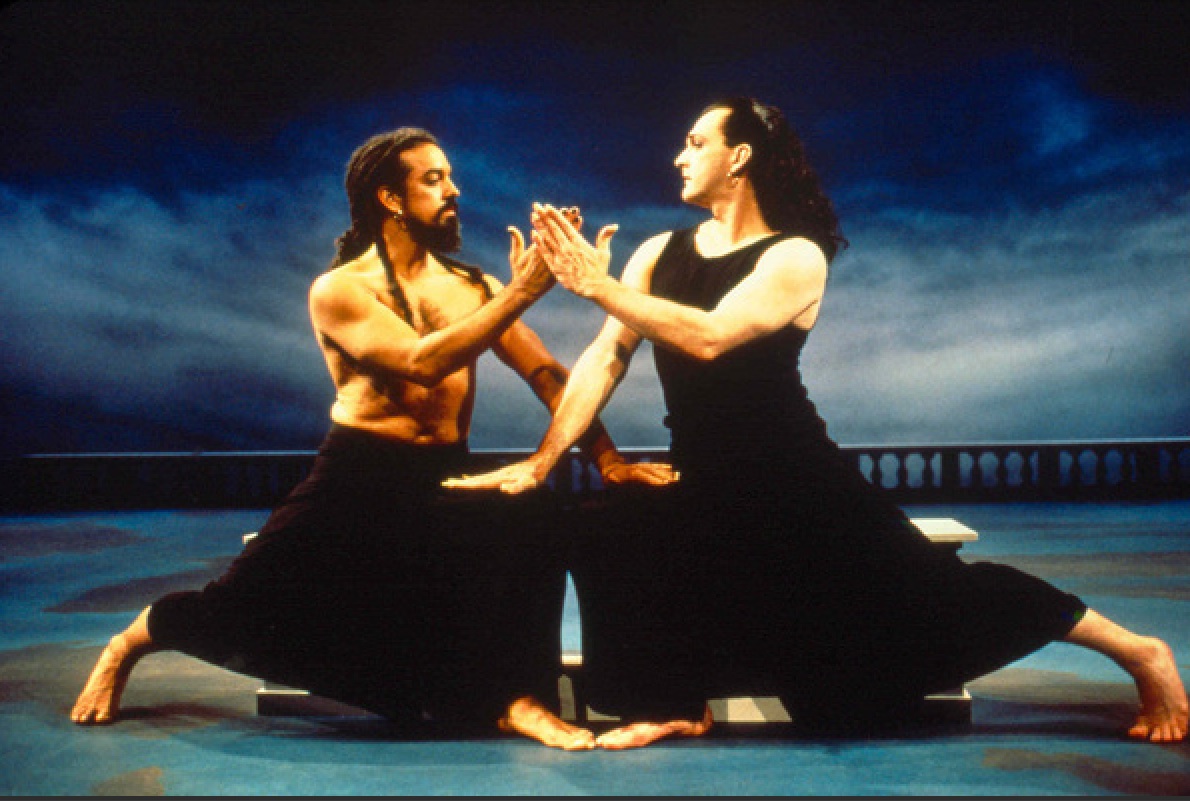

At the 1989 premiere and subsequent performances, Morris—a large man in both personality and physique, dressed in the same black billowing pants and tank tops as the other dancers, with the tips of his ears and lips painted red and fingernails long, with curly hair cascading down his back, and paired with a smaller male dancer (Guillermo Resto) as Aeneas—danced his way into legend. “As he said at the time,” Acocella wrote in 1993 of Morris’ decision to play the dual role, “he wanted to expand the expressiveness of male dancers; he wanted to give them what women had. But, artistically, the more important fact was that the gender switch—plus the combining of the heroine and villainess roles—shot the show into a mythic territory, beyond realism and beyond conventional morals.”

Morris stopped performing the role(s) in 2000, but the company continued to stage Dido and Aeneas, with a woman from the company dancing the parts. “Gone is the Asian-theatre mystery of the opera, the idea that the Queen could be a man, an icon, a principle,” Acocella wrote. “She is now a pretty girl from Oregon, and that changes the show radically, restores it to realism. It is impossible not to regret this, but in doing it Morris saved ‘Dido.’ The way to lose a dance—and thousands of dances have been lost thereby—is to stop performing it. The way to preserve it is to recast it and recoach it and put it back onstage.”

The current tour of Dido and Aeneas, performed by the Mark Morris Dance Company at Northrop recently, has Morris conducting the live orchestra and singers, while Laurel Lynch dances the principal roles. Twenty-seven years after its premiere, now that AIDS has receded in our cultural consciousness due to education and advances in medical treatment, gay marriage is legal, transgender actors and activists and artists are cultural ambassadors for tolerance, and the first woman is running for U.S. President, what does this piece bring to an audience? Inarguably, the work is gorgeous, iconic, timeless, legendary. But is it possible to see more in the work than Morris’s legacy?

Inarguably, the work is gorgeous, iconic, timeless, legendary. But is it possible to see more in this reiteration of Dido and Aeneas, 27 years on, than Mark Morris’s legacy?

With Lynch in the dual roles of Dido and the Sorceress, it’s not difficult to give the work a feminist reading. There’s the obvious virgin and whore (respectively) scenario, as well as the story of a powerful woman destroyed by a man, aided (if unwittingly) by the petty vindictiveness of another woman and Aeneas’s destiny (wittingly, although as ordained by the gods) as a powerful leader. In Morris’s Dido and Aeneas, however, things are a bit more complicated than that.

It’s hard not to love Dido, whose formal, restrained movements are twisted into a flattened, frieze-like two-dimensionality that is mirrored in turn by her subjects (the work’s chorus) and Aeneas. Her gestures proclaim the contained power and passion of a woman who created a city out of ruins. (The flattened angles of Morris’s choreography also evoke Nijinsky’s faun and the then-iconoclastic movement Nijinsky created for the 1913 Rite of Spring.) Dido’s hands protect her heart. She kicks her foot to stave off Aeneas’s advances. She’s bigger than her suitor, and similarly fierce, with a defined musculature that exudes decisiveness. But Dido is no match for love, apparently, as she gives in to Aeneas.

Nor is the Queen a match for the Sorceress, who slithers, shudders, rails, and flings herself about with conspiratorial mirth, pounding the floor with unleashed, erotic fury. Like a figure out of Bruegel, or rather Bosch, the Sorceress is wholly three-dimensional, loose-limbed, and so butch as to be campy at times, as if she were a man in drag playing a woman. Lynch manages this phenomenal transformation through movement, gesture, and characterization. Dido’s long curly hair, pinned up off her face, literally comes down, and the Queen’s long silvery fingernails flash with metallic menace when Lynch becomes the Sorceress.

The Sorceress is deliciously evil, and her chorus follows suit. There’s a sassy sailor dance, with Irish step dance inflections; fingers splay into the poetically gestural hands of a classical Indian dancer; circles evoke the ritual folk dances of European cultures: Morris studied and performed all of these dance styles. All the while, Morris’s choreography gives visual meaning to the music: dancers’ arms rise and fall like dominos to rising and cascading notes, the singers’ wavering trills are echoed in wriggling shoulders, and hips swing as strings sing. Not only the music but the words matter—even if you’re not a music scholar or can’t read the program in the dark.

Aeneas leaves. Duty and demonism win. And even Dido urges him to go. Picturing a woman undone—and Lynch portrays her simply lying across Dido’s bench, her seat of power usurped by her own passions and those of others—bears a sense of tragedy that’s timeless across cultures, with a contemporary relevance in the politics of a 21st century still, bewilderingly, embattled in myriad ways around the rights of women to control their own bodies, lead companies and countries, and experience full equality to men.

“Remember me but forget my fate,” a soloist sings as a yearning Dido, before her death, bends and lengthens her arms beseechingly toward the chorus. She embodies both Dido’s mythic demise and what could be interpreted as Morris’s or any artist’s plea to be remembered. In the largest sense, perhaps it’s the most basic human impulse. Remembrance, in life as in death, is all anyone could ask for.

Related links and information: Mark Morris Dance Group performed Dido and Aeneas with a live orchestra at Northrop on March 30, 2016. Find background on the company and this work, including a number of videos detailing its history in performance, via the Mark Morris Dance Group’s website.