A Matter of Honor: Becoming a Tattoo Artist

Chris Olwell looked into what it takes to become a tattoo artist; he hung out with Dave Zappia and his apprentice Will Richards.

The first time Kait Craig met Dave Zappia she walked away scarred for life, but there’s no reason to be surprised that she came back for more.

“I just think it’s a really creative way to express your self,” Craig said. “It’s like an addiction, but it’s better than doing drugs.” This time she walked away with a new scar: another tattoo, this time the Scottish-Gaelic symbol for “faith eternal.”

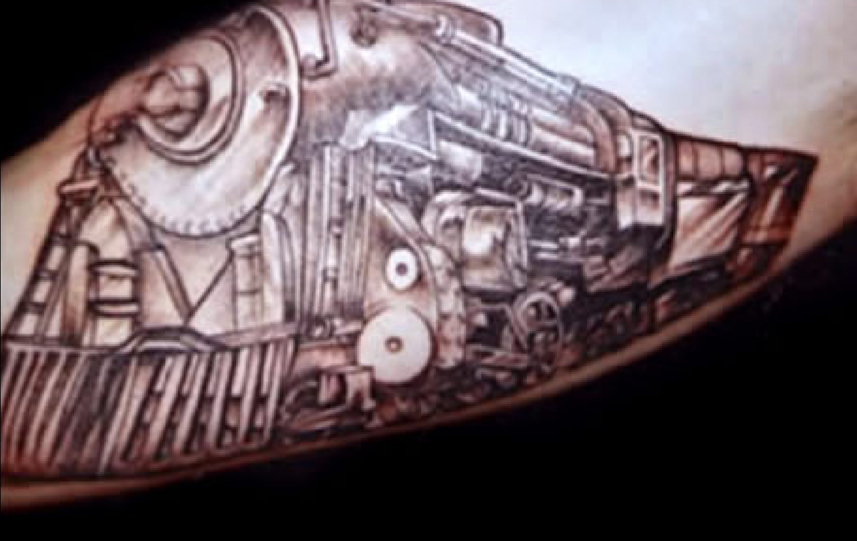

Zappia is the owner of Dominick’s Metal Shop, one of three tattoo shops in a two-block stretch of W. First Street in downtown Duluth. He is also a preferred tattoo artist for Breaking Benjamin, a heavy metal act of repute that invited Zappia to join them on a recent nationwide tour. It was an invitation he was thrilled to accept.

“It feels really good that people who are that recognized – people who could have any tattoo artist they wanted – and they chose me,” Zappia said. “I tattooed the whole crew, the whole band, in a day.”

The Apprentice

Zappia’s come a long way from where he started out, 10 years ago, after he finished his apprenticeship. In fact, he’s had several apprentices of his own. Will Richards is one of them.

Two years ago, Richards was going to technical school to become an auto mechanic. Tattooing, Richards said, “kinda picked me.”

He’d always considered himself to be artistic, but Richards never saw himself as a tattoo artist until he met Zappia a few years ago through his brother-in-law, another tattoo artist. Richards had painted some signs for Zappia. When the opportunity for an apprenticeship with Zappia arose, Richards dropped out of technical school and never looked back.

“He was already an aspiring artist that had been doing certain freelance work for me,” Zappia said.

An apprenticeship in the tattoo business is like going to college, except you get paid. “But you gotta pay some dues,” Zappia said. Richards spent the first six months of his apprenticeship practicing on paper. That’s right, drawing. “I was not even thinking of touching a machine.”

All of Zappia’s apprentices have started out that way. “It’s all on paper. No one’s doing fruits or vegetables,” Zappia said, referring to an alternative training method.

And like a college work-study program Zappia’s apprentices earn their keep producing t-shirts while they learn the basics of sterilization and customer service. Some shops charge money for an apprenticeship.

But, as independent contractors, the artists at Dominick’s aren’t getting paid if they’re not tattooing, so Zappia offers minimal compensation to apprentices before they begin working on skin. “The employees that I bring in are passionate about it,” Zappia said. “I’m not looking to ask them for money. I’m here to say ‘no, just dedicate yourself, live on minimal means . . .

and the money will come to you.’” Apprentices command lower hourly rates and generally work slower than their more experienced counterparts, so they need to be prepared to live on little while they’re training.

Money is a touchy subject for some of the artists at Dominick’s. One did not want people thinking that tattooing was lucrative. “There are some things you don’t tell people outside the industry.” He said this not to protect his livelihood, but to protect people from hacks. “If someone thinks they can make money doing this they’ll get a machine off the internet and start scratching kids in their basement. It’s more complicated than that.”

Which brings us to another trait common to all apprentices: “They all fuck up,” Zappia said. “You gotta crawl before you walk.” Richards, for instance, once got the dates wrong on a memorial tattoo. It was not his fault, he tattooed the dates he was given, but the wrong date is still the wrong date.

These things happen, and, despite the permanence of a tattoo, they’re not impossible to correct. It just requires a little extra creativity on the part of the artist. “I had to come up with a way to change it,” Richards said. “It wasn’t that bad.”

Now half-finished with a four-year apprenticeship, Richards has seen his confidence rise as he’s gained experience. His limitations are disappearing. Notoriously difficult body parts, such as hands, feet, necks, and stomachs, are no longer beyond his capabilities. He feels ready to take on more intricate designs, like Celtic knots, but Zappia likes to take things one day at a time.

“We want to focus on what happens today and now for him to progress before we talk about what happens later,” Zappia said.

Zappia tries to cultivate an appreciation for the art form in his apprentices, and for him that starts with the people who wear his art. “I really try to treat each tattoo as an individual act,” he said. “I always try to incorporate something about each person’s personality into a tattoo.”

Richards agreed. “Doing tattoos you get to interact with people. You meet so many different people. It’s a rewarding art form,” he said. “You get to have a piece that is going to be on somebody for the rest of their life so . . . it’s kind of an honorable thing.”

Honorable? It’s probably not the first word that comes to mind when you think about a tattoo artist, but the industry has come a long way in the past few years. Whereas tattoos were once the mark of sailors and convicts almost exclusively, “we’re piercing doctors and dentists now,” Zappia said. “Ten years ago it was nothing like it is today.” If not quite honorable, tattooing has at least reached respectability.

With respectability comes responsibility, and Zappia takes his responsibility to the community very seriously. That means checking IDs and requiring parental consent from teens. It means refusing to do gang tattoos. It means turning away intoxicated customers.

“I really feel that’s what we’re here for. Not only are we here for our own benefits and our own personal gains, but we’re also here, as a team and as crew, to support the community,” Zappia said. “Okay, when you’re 16, no, we’re not going to tattoo you even though we legally can because we don’t think that’s actually benefitting you as an adolescent or your parents in regards to raising you.”

After all, tattoos are a family business for Dave Zappia. He learned his craft from his father, Dave Sr., an artist for over thirty years. Now a father of three, Dave Jr. plans to keep it in the family; Dominick’s Metal and Gear takes its name from his oldest son.

Rico’s Sun

“Rico,” as Mike Talarico prefers to be called, came into Dominick’s for some fresh ink on a recent evening. He wanted “something that looked kinda sunny, but kinda creepy at the same time.” Talarico decided on a tribal sun he found in one of the books in the lobby, and also got an old tattoo touched up.

“I’m heading down to Corpus Christi in a month,” Talarico explained as he sat down in Richards’ chair, “so I’d like to get a little sun on it before I go.”

Richards and Talarico made small talk for most of the hour or so it took to put the sun on his left biceps. Topics of conversation included the Rush song playing on the stereo and Reggie, the eight-foot-long albino Burmese python that lives above the entrance to the shop. The tattoo caused Talarico no visible discomfort.

“I like it. It wakes my ass up,” he said. “There have been times, though, like my chest . . .” Talarico pulled down his black tank top to reveal a large tattoo spread across his upper chest. He tapped his sternum. “This had my eyes watering.”

Richards applied the tattoo without incident. As he bandaged the biceps he explained how to properly protect the new tattoo from the sun. There’s nothing more dangerous than the sun for a new tattoo, he said, especially in the first couple weeks.