A Marriage of Art and Scholarship

Hannah Dentinger looks into the career of internationally acclaimed artist and educator, Ann Ledy. After a distinguished career teaching for NYC's Parsons School of Design, Ledy has returned to her native St. Paul to take the helm at CVA.

MUCH OF ANN LEDY’S ARTWORK EXISTS IN BETWEEN—between drawing and collage, between sculpture and installation. Often, too, it hovers between dimensions. A series of steel plates embedded in a wall, 1995’s untitled 7 casts pointy shadows like the teeth of a saw. Arranging shadows on floors and walls is one of Ledy’s methods of drawing. Images are, of course, visible only because of the action of light absorbed or reflected. But rarely is light the actual medium of a work of art. So what is untitled 7? Is it a drawing, or is it a sculpture? Is it two dimensional—flat metal and flat shadows—or three-dimensional?

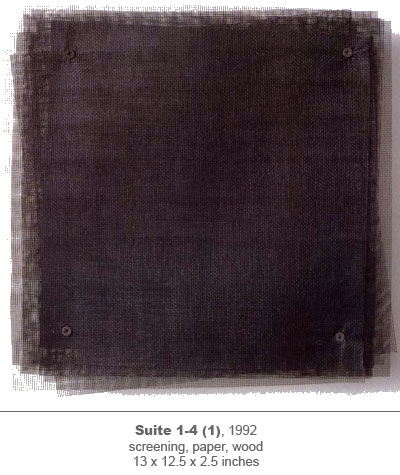

Such ambiguities set up a subtle tension in Ledy’s work. Suite 1-4 (1) (1992) is, at first glance, a dark square foot of graphite rubbings. Look again, and it materializes into layers of screening and paper secured with a screw in each corner. It courts two dimensionality, but textured layers buck any such simplification.

Ledy’s techniques marry the artist’s studio and the industrial workshop just as Suite 1-4 (1) merges the fragility of paper with the toughness of metal in an interaction reminiscent of the manufacture of books. Indeed, she cites as a turning point in her work her experiments with books, with fabricating and deconstructing them “in an effort to rebuild my vocabulary.” This gave rise to the pieces showcased here, which Ledy handpicked for mnartists.org both because they reproduce well online, and because they hang together as a body of work.

Since the early 1970s, Ann Ledy’s work has been shown almost constantly in group and solo shows throughout the United States and in Europe and Asia. This year, she is being featured in an exhibition at San Diego Museum of Art entitled Dimensions in Nature: New Acquisitions, 2006-2008. And 2009 brings another transatlantic foray as her work will be shown at the Museo de Arte Contemporaneo Esteban Vicente in Segovia, Spain.

Ledy has been collected by museums including the Walker Art Center, the Baltimore Museum of Art, MOMA and the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. Werner “Wynn” Kramarsky is a New York expert on Minimalist and Post-Minimalist art whose nationally-known collection of works on paper also boasts an extensive catalogue of her work.

Given her redoubtable credentials as a working artist, it may come as a surprise that Ledy has also thrived in the academic career she envisioned for herself as early as college. Ann Ledy grew up in Saint Paul, where her mother taught English and her father owned a small business. Her mother was a talented amateur musician who, Ledy recalls, also enjoyed the visual and performing arts and encouraged her daughter’s interest in them. She would bring Ledy to the Minneapolis Institute of Arts and the Walker Art Center for drawing and sculpture classes; she recalls that on family vacations art museums were always part of the itinerary.

“Drawing was my first love,” Ledy remembers. “I was given an oil painting set in junior high and taught myself how to use the paint.” Her interest in the visual arts deepened when she attended Alexander Ramsey High School in Roseville, a school known for its outstanding art department. There, in addition to drawing and painting, she also experimented with printmaking. Even today, Ledy names Merle Clerx, her high school art teacher, as a significant influence. She elaborates: “He not only taught me how to paint, but how to apply and discipline myself. He held my feet to the ground and showed me what it meant to study. He’s my role model as an educator.” A very serious student who, from the beginning, was committed to becoming an artist, Ledy went on to study at the University of Minnesota. Despite her interest in drawing and printmaking, she recalls, “I discovered that I wanted to work with a more immediate medium, consequently, I turned to painting.”

Peter Busa, Victor Caglioti, and Katherine Nash were notable figures in the art department at the University of Minnesota in those days. Nash was the only woman teaching in the art department at the time. “She was tough and independent,” Ledy says, and she remembers Busa as “an inspiration and a force to contend with” while “Caglioti provided clarity and reason.”

The Twin Cities in the early 1970s had a vibrant arts scene. Eager to have her own studio, Ledy rented “a raw space in downtown Minneapolis above what was to become the New French Café,” not far from where Busa and his partner were renovating a loft. But early on, she felt the pull of the East Coast: “The center of the art universe was NYC, and I wanted to be there.”

Ledy credits Busa, Caglioti and Nash with giving her the “chops to go to New York in pursuit of my dream. I was determined to live the life of an artist in NYC,” but, significantly, she also wanted to teach drawing at a college. After graduating summa cum laude from the University of Minnesota, she began an M.F.A. at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, where she worked with talented faculty but was also inspired by the richness of New York City’s cultural offerings. “The most important component to my development as both an artist and educator,” she says, “was my exposure to the major galleries and museums of both art and design in NYC.”

_________________________________________________

“I was determined to live the life of an artist in NYC,” she says. But, significantly, she was equally driven to teach.

_________________________________________________

Soon after her graduation from Pratt, Ledy was hired by Parsons School of Design in New York to help administer the Higher Education Opportunity Program, a need-based program for disadvantaged applicants to private New York colleges. During the summer, she taught drawing. She went on to teach drawing and painting courses at both Pratt and Parsons and, in addition to showing her own work regularly, ran independent drawing and painting workshops out of her private studio that resulted in her organizing and teaching two site-specific drawing workshops in Greece and Turkey and in Paris.

Ledy was then appointed to run the Foundation program at Parsons, a mandatory studio program for first-year students in design that also involved liberal arts work in English and art history. The student body was wonderfully diverse. “We averaged five different languages and cultures in any given studio class and enrolled students from some forty countries,” Ledy remembers.

A renowned school, Parsons drew students from all over the world to New York, but it also maintained a presence in far-flung places with affiliate programs in Kanasawa, Japan; Altos De Chivon, Domincan Republic; and Paris, France. Ledy was tasked with restructuring these programs, as well as creating new ones in Seoul, Korea and Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. She was responsible for hiring and training new faculty in each of these locations, and calls the process “a cultural education” that had an impact on her artwork as well as on her academic career.

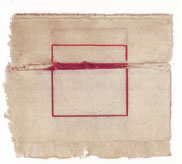

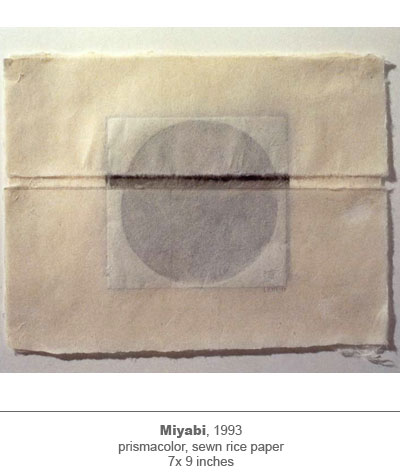

Japanese architecture, traditional gardens viewed in Kyoto and even Japanese court poetry were influences subsumed in Ledy’s style. For example, Yugen, translated as “mystery and depth,” is the title of a 1993 drawing: a simple square outlined precisely in red that contrasts with the rough edges of the folded rice paper on which it is executed. The barest pencil outline of a circle can be discerned within the square, and Miyabi (1993; translated as “courtliness, elegance”) picks up the motif: a smoke-colored circle fits inside a square white as grease paint and traced on creamy rice paper.

Ultimately, Ledy became Chair of the Foundation Department at Parsons, but in 2004, she made the decision to return to her native Saint Paul to join the College of Visual Arts (CVA) as the Executive Vice President and Dean of Academic Affairs. “It goes without saying,” Ledy says, “that the Twin Cities is an extraordinary art center.” But Ledy also describes her move itself as “an extraordinary opportunity. My academic career has consisted of building, reshaping, and expanding programs to support students’ academic growth and development through the visual arts. In this way, my experience matched the needs of CVA.”

Among her proudest accomplishments at CVA thus far is her success in creating what she terms “a well-defined four-year experience.” Students prepare to enter their field of choice with an internship program, liberal arts courses (including math and science), and off-campus study opportunities in Paris and New York. Not only that, but CVA hosts both regionally and nationally curated exhibitions in its galleries, alternating these with student, alumni and faculty exhibitions.

Just recently, Ledy became the President and Chief Academic Officer of CVA. This is a college where just over 50 teachers serve an intimate student population of 200. All seven of CVA’s full-time professors and each of the 45 adjunct members of the faculty are working artists.

_________________________________________________

Steel and aluminum, nails and screws are as much a part of Ledy’s toolkit as paper, fabric, vellum, graphite and ink.

_________________________________________________

Ledy, of course, understands only too well the challenges of growing and producing as an artist while being fully committed to a demanding academic position. She acknowledges that her hardest task, still, is to balance her administrative duties with her own artistic pursuits. In fact, this Thanksgiving, she told me, she headed to Florida for an intensive week of work in a friend’s metal shop.

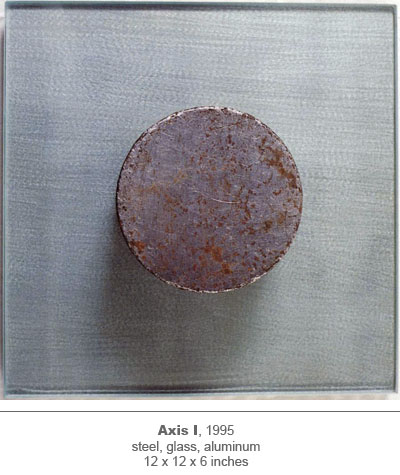

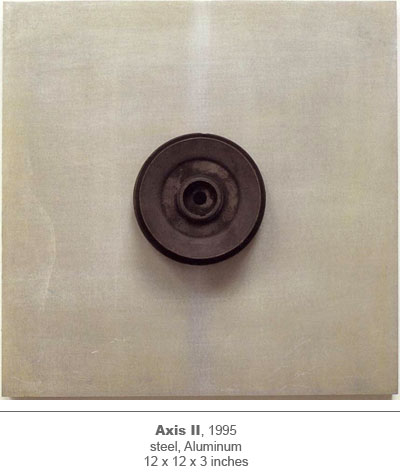

Steel and aluminum, nails and screws are as much a part of Ledy’s toolkit as paper, fabric, vellum, graphite and ink. Although she specialized in painting for her undergraduate and graduate work, she has a long history of working with industrial processes and materials. Her father started a business engraving nameplates in the basement of the Ledy family home in 1958. Gradually his work expanded to include plastics machining for electronic equipment manufacturers, screen-printing, graphic overlays, panels and decals. GML Specialties grew further to provide corporate clients like Target and Best Buy with signs and displays. Ledy worked at GML in various capacities throughout high school and college. “Growing up around machinery gave me the confidence to work with industrial materials and equipment,” she reflects, “thus influencing my artwork.”

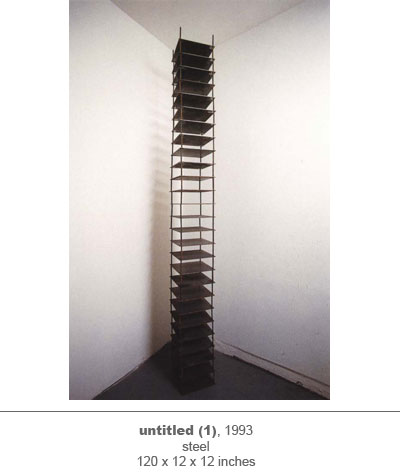

This early exposure to design principles must also have helped to equip Ledy for her career at Parsons and CVA, where industrial, product, and graphic design are taught alongside drawing, painting and sculpture. Ledy’s own sense of design is also colored by her interest in modernist architecture. Her ability to work on a small scale for pieces like the diminutive Yugen and Miyabi is, again, balanced by her eye for larger formats, as in an untitled piece from 1995 (untitled (1)) that resembles a ladder abutting on the ceiling of the installation space.

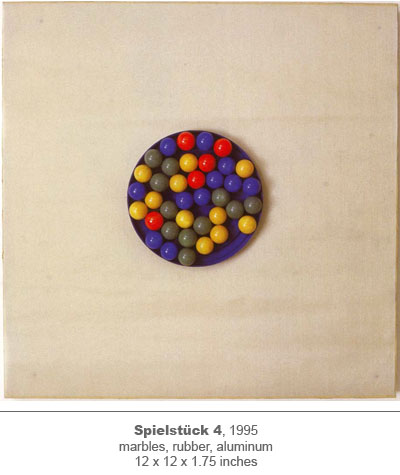

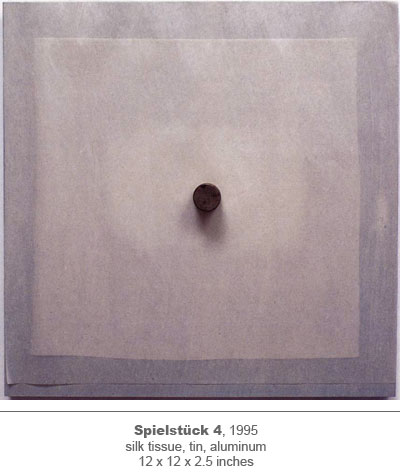

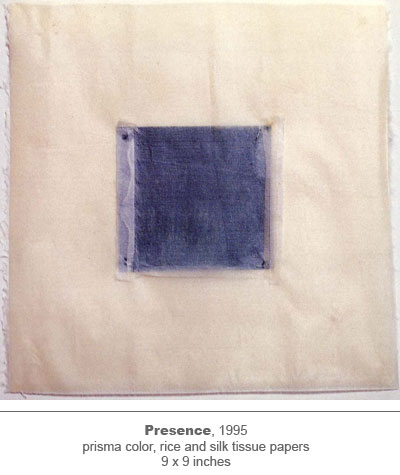

Ledy’s work is controlled, serene, subtle. She favors what she calls “atonal” colors—buff, tan, charcoal, the rusty brown of walnut ink and the oily brown of steel—for what she has called her “exquisite objects” rather than drawings or paintings. Bright primary colors are occasional accents, although Ledy’s early work was figurative and her “color palette…almost baroque.” An exception is Spielstück 4 (1995) which consists of colorful marbles arranged within a rubber circle in the middle of a sheet of aluminum. It strikes a playful note—indeed, the word “Spielstück” is based on the German for “play.” The term refers to a piece of music, perhaps harking back to Ledy’s mother’s study of classical music as well as invoking a memory of her father’s German ancestry.

Perhaps it is her mother’s love of the performing arts that Ledy channels when she describes the surprising convergence of skills germane both to academic administration and to artistic endeavor: “As an academic leader,” she muses, “I liken myself to a choreographer. It is my job to pull together the various components of the college, and then bring them to life. The job of a studio artist is not too dissimilar.”

_________________________________________________

About the author: Hannah Dentinger writes on art and literature. She is also a scholar of medieval Welsh literature.