A Convert to the Cult of Frida

Poet Lorena Duarte offers a personal and historic glimpse into the forces which turned Frida Kahlo, the artist, into Frida, the social and cultural icon she has become.

My first really weird Frida Kahlo moment was when I saw a Frida switch plate.

Mind you, I had known about Frida Kahlo for years and was impressed by her art, her daring images, and her combination of car-crash/look-at-me-dramatics with femme-fatale allure.

But it was in a small house in East L.A., when I was groping for the bathroom light, that I came to think: really, truly, what is it about this woman? What would possess someone, anyone, to install a Frida Kahlo switch plate in their bathroom? What is it about her that is so alluring? Is no one else a little creeped out by how ravenous people are for her?

Fast forward a few years, and here I am struggling to condense all my collected Frida knowledge and anecdotes into an hour-and-a-half lecture for the Walker, which is scheduled in conjunction with their current exhibition of her work. I admit it: over the years, I have become Frida-fied. I have caught the fever, the holy ghost of the Frida, and, agnostic though I may be, I must say: Amen!

So, what’s behind my conversion into a bona fide, unibrow-wearing member of the cult of Frida? What makes her so unique, so irresistible?

There are obvious reasons to find her fascinating, of course; she was openly sexual, not a little bizarre, and utterly unique. And let’s be honest: her work is shocking. In Broken Column (1944), she presents herself naked, broken and pierced with nails. Some paintings are filled with disjointed, jarring imagery, like that in What the Water Gave Me (1938): skyscrapers emerge from bursting volcanoes, while Kahlo’s own parents watch over a lesbian love scene taking place on a sponge-raft. Frida’s are symbol-laden images, full of heavy portent and incongruent iconography. My Nurse and I (1937) portrays Frida as a half-child/half-woman, suckling from a monumental masked figure. Similarly unsettling, Girl with Death Mask (1938) confronts you with the dissonance between the little girl’s innocent pink dress and her ferocious death mask.

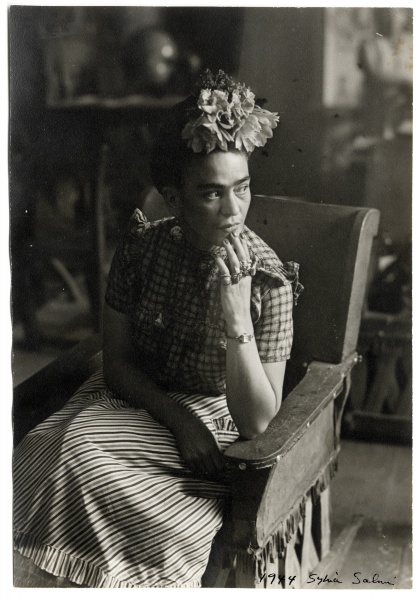

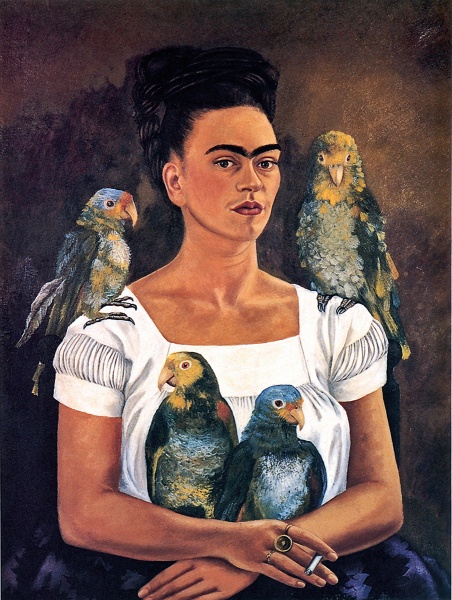

Beyond the sheer shock value of her work, there is no doubt that Frida is also a master seductress. Her self-portraits reveal a woman who is open and vulnerable, yet she remains self-possessed and hidden to the viewer. She allows us to see her cry, but the tears she portrays herself shedding have an almost wooden, artificial quality. They are the tears of a mask, not the natural tears of a weeping, flesh-and-blood woman.

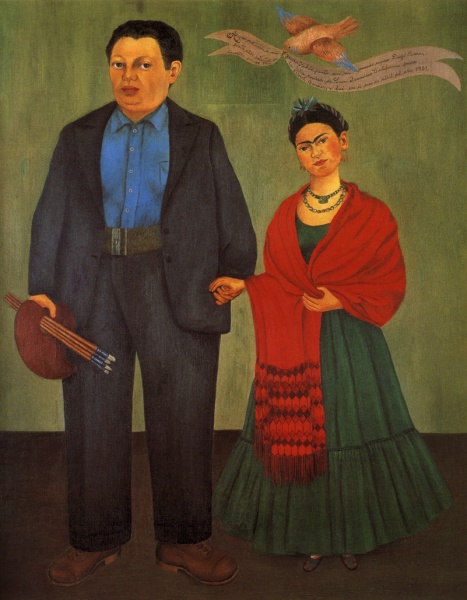

Then there is her cheeky humor. I know what you’re thinking: how can I claim the woman who painted Without Hope (1945) is funny? Cheeky? Here’s just one instance (among many) in her work, where her keen wit is evident: in the famous Frida and Diego (Wedding Portrait) (1931), she portrays herself as a tiny, demure Mexican housewife—the little woman (literally) next to the great maestro. But looking closely at the inscription in the top right hand of the painting, you find two great jokes. First, she has borrowed this type of inscription from the religious tradition of offering ex-votos, which usually serve as an invocation to the heavens. How ironically self-aware she is to paint her wedding portrait to Diego thus, as if she knew it would require some sort of heavenly intervention to stay married to the devilish Diego. Second, she dedicates this humble little painting to Albert Bender, one of the great art collectors of the West Coast, and in so doing, slyly establishes for the viewer (if they aren’t already aware) her elevated position in the art world. So cheeky, so Frida!

Of course, most people don’t see funny when they see Frida’s paintings. They see the drama and the suffering. And it’s true; she does expunge her pain onto the canvas. For women in particular, that was a powerful and liberating act. She is the first to have tackled with such brutal honesty all those private things that we were never supposed to talk about: sexuality, bisexuality, childbirth, miscarriage, the brutality of machismo. And for us Latin American women, she is even more astounding. Frida was born around the time of my grandmother. I cannot imagine my grandmother—or any woman of that strict post-colonial, Catholic generation—living as Frida did.

Still, while pain and suffering is evident on her canvases, so is the notion of endurance, of living through it, and of hope. Even in paintings like The Little Deer (1946), in which she is depicted shot through with arrows, there is in the distance a gorgeous, bright blue landscape, sky and ocean. Both the imagery of the little deer (for which she wrote a lively and sweet Mexican folk song called a corrido) and the presence of so much blue—in her personal lexicon of color, indicative of purity, tenderness, and love—offer important evidence of her optimism. And, if you look closely, in the seemingly dead trees that surround the deer-as-Frida, there is new growth peeping through.

The same hope and passion for life with which she painted also served to create Frida into a powerful icon. She clung fiercely to life; she reveled in it and consciously recreated herself into an icon. She understood and exploited the power of pomp, costume, and ceremony, and of bringing what is private into the public sphere. Walking into a room in her regalia of jewelry, flowers and rustling petticoats, Frida could stop orchestras (as Carlos Fuentes recounts).

That power, that magnetism was enhanced by the fact that she and Diego were at the hub of an incomparably intellectual, social, political, bohemian, and artistic community that stretched across the world. She was sufficiently intimate with Andre Breton and his friends to call them “the artistic bitches of Paris.” Frida was admired by Picasso, and slept with Leon Trotsky. Frida was innately aware of her place in that community, and what her legacy could be.

That self-awareness, however, has drawn to Frida accusations of narcissism and intimations that she has no interest in others. But if you understand her politics, you will see that whatever political ideologies she may have espoused, Frida’s own words, paintings, and the way she lived all demonstrate an abiding personal conviction for peace and justice. She always felt a moral pull towards equality and speaking out for the disenfranchised. She wrote: “To feel in my own pain / the pain of all those who / suffer and inspire me / in the need / to live in order to struggle / for them.” She wrote further: “I would like to deserve something, along with my painting, from the people to whom I belong and the ideas that give me strength. I would like my work to contribute to people’s struggle for peace and liberty.”

Perhaps her most consistent political stance is the fierceness with which she embraces her Mexican identity and, at the same time, rejects European, American, and Colonial aesthetics and norms. Seen in this light, nearly every act in her life, from getting dressed in her Tehuana finery to sleeping with women, could be seen as highly political, private acts of defiance. Her criticisms of the USA are witty and cut to the bone. For example, in My Dress Hangs There (1933) she paints the two trophies of American obsession, sports and plumbing. She portrays them as the trite concerns of an infantile country consumed by its own capitalist greed, in sharp contrast to the ancient, earthy (as in real and tangible, covered in dirt) concerns of Mexico.

All of this—her persona, her politics, her humor, her fierce passion for life, her shock-value—inspires, seduces and entices us to look at her, to consume her. However, in the cult of Frida, perhaps the most overlooked source of her lasting attraction lies simply in her artistic ability, in her talent as a painter. So much of the fascination around Frida is biographical: Who she was sleeping with? Was her mustache really that dark? How many operations did she have? Why did she put up with Diego? Her paintings get put on coffee mugs and people forget to really see them—which is a damn tragedy, because, as a painter, she is extraordinary.

Her work is remarkable, unique—then and now—innovative, and intentional. I have heard people say: Yes, Frida painted shocking things but she could not paint. That is a sad misunderstanding of her intentions. She chose to follow her roots and paint in the style of Mexican folk traditions, but she took those traditional forms and invented a whole new worldview with which to understand them, one that clashed modern realities with long-standing sensibilities. She appropriated traditional ex-voto offerings and turned them into secular commentaries on society. (See Henry Ford Hospital, 1932; or A Few Small Nips, 1935.) She took both indigenous and Catholic iconographic images and blended them in disturbing, brilliant combinations (Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird, 1940; The Two Fridas, 1939; The Love Embrace of the Universe, the Earth (Mexico), Me, Diego, and Mr. Xolotl, 1949).

In the end, the cult of Frida includes so many—from Latinos and feminists to members of the GLBT community and Minnetonka housewives. It is astounding.

I stand before her paintings and wonder what Frida would think. Would she laugh? Would she revel in her iconic status? Would she be disgusted by all the American-style consumerism surrounding her and her paintings? As with anything to do with Frida, there is no easy answer.

In the end, as a writer, and as someone who has come to know a great deal about her, all I can boil it down to is this: Her appeal is unquestionable, and for all the madness and scandal that might surround them, it is her paintings that distill the essence of this woman, of her attraction.

I stand before her paintings and hear Frida say: Appreciate the beauty around you. Look at the horrors of the world and be grateful for what you have. Look inside yourselves, as I have done. What do you see when you look in the mirror? Be brave, be funny, laugh, and, above all, dare. Dare to love, despite the agonies it brings. Dare to walk, even when you are broken. Dare to survive.

So to end the story, guess who I dressed up as for Halloween this year? That’s right; I was Ms. Frida Kahlo, unabashedly wearing my unibrow with pride. Take my advice: pass on the switch plate reproductions of her art, and go see this exhibition. Truly, Frida’s work suffers greatly from reproduction. In person, these pieces are otherwordly. And when you see her work, say Amen—to the blasphemous, life-ravenous and amazing Frida.

About the author: Lorena Duarte is a poet and writer living in the Twin Cities. She has a degree in Hispanic Studies from Harvard University and she is teaching several classes on Frida Kahlo for the Walker Art Center in conjunction with their current exhibit.

What: Frida Kahlo

Where: The Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, MN

When: Exhibition runs in Minnesota through January 20, 2008; this spring, the show will continue from the Walker, to tour in Philadelphia and San Francisco.

Tickets: Visit the Walker website for admission details and information about related events.