The Columnest Goes to New York

Everyone says that New York has never been more and less central: the capital of the world, agglomerating liquid power, know-how, and UHNWIs (what’s that? Ultra High Net Worth Individuals, of course), expelling artists and beekeepers to the outer boroughs and beyond.

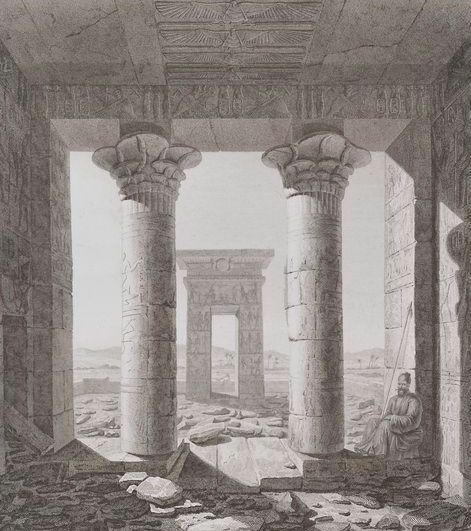

Went to New York a few weeks ago. Everyone says that New York has never been more and less central: the capital of the world, agglomerating liquid power, know-how, and UHNWIs (what’s that? Ultra High Net Worth Individuals, of course), expelling artists and beekeepers to the outer boroughs and beyond. Indeed, Brooklyn struck me mostly as a lot of Durham—or Uptown Minneapolis, or Portland, etc, etc—plus, yes, brownstones, street fashion, and fantastic museums. New York is still New York, where you fall in love seven times a day, get your ass handed to you about as often, and then stumble into the tenderest silence in the shade of the Temple of Dendur.

New York preaches the gospel of standing out from the crowd. I can see why so many New Yorkers have tattoos: you can’t be the buffest guy or the prettiest girl, you can’t have the shiniest hair or the most de mode haberdashery (because in New York there are people who make these things their jobs), but you can think up an original wing or word to emblazon on your shoulders or across the first joint of each finger. Dye your hair pink, for god’s sake! But not just any pink: cotton candy’s taken. I’m talking appearance because a flashy front is the quickest route to attention, but the same holds true in any arena. I recall a composer friend, resident in Brooklyn, running through genres in which other people could do as well as he, genres he accordingly dropped in favor of the one category in which he excelled everyone he knew. Shave yourself to a point. It makes sense!

That is, it makes sense in New York. Four days in the metropolis honed my game to the point where I vowed I’d never wear a less-than-magic blue (one tick off that teal and my eyes don’t glow) or write a line without fireworks, but the minute I got home to North Carolina, I chilled out. People, like plants, live relatively; put me in a rioting jungle and I will strain to reach that single crack of light, but set me on a rolling plain and I will spread this way and that, lackadaisically.

But is that really the question? Isn’t New York reality—everyone bunched together, the better to see where you stand? People go to New York to find out, and New Yorkers—by which I mean, as they mean, people who’ve lived there long enough to say they’ve survived—will fervently tell you their stories of clawing through to the real me: the lasting individual genius. Do you want to play the big game? New York asks you, and damn it’s persuasive about what that game consists of. The little island of Manhattan, bristling with buildings and bright all night, tunneled with subways, plastered with signs, every inch taken: this cityscape forms a spatial representation of the density of historical time. The skyscrapers are Shakespeare, Dickinson, Stein; or Picasso, Cezanne, Raphael; or Josephine Baker, Fred Astaire, Merce Cunningham. Walking those streets, you are an aspirant ant, and you can see exactly how far you have to go.

I’m making it sound terrifying and depressing, but as anyone who’s been there knows, it’s exciting! The streets are full of ants gazing upward, and the city hums with that hope and ambition: it is possibly the most optimistic place in America.

But let me interrupt myself for a moment: whence these adverbs, these exclamation marks, these enthusiastic eruptions? Obviously, I’ve been reading Frank O’Hara, preeminent poet of the New York moment. “I have in my hand only 35¢, it’s so meaningless to eat!” he exclaims in Music, a poem (like many of O’Hara’s) devoted to the temptations, sensations, and flurries of the immediate present, which nevertheless winds up with a wistful glance at the coming holiday season, in which there will be

no more fountains and no more rain,

and the stores stay open terribly late.

Note the adverb: O’Hara relies on these much-reviled parts of speech to suggest the ways the world’s colored by the perceiving mind. Now I am put in mind of the adverb “hopefully,” which we have all given up trying to use correctly—it means, or it used to mean, “full of hope,” as in “He grinned hopefully,” and it is misused in an expression such as “Hopefully, the door will open”—and this strikes me as somehow connected—because we are unable to keep our emotions, our hopes, from washing over the world we see.

That’s what New York does to me: theories and clauses springing, leapfrogging one over another. Half the time I can’t make sense of my notes when I get home.

At home just now, the tree people (mistakenly labeled “Tree Experts” on the side of their truck) have insulted rather than injured a massive and interfering ivy and butchered a maple, feeding half its canopy into their mobile chipper. There’s no sense saying anything to them. They’re just kids who’ve grown inured to their ugly task. But the poor tree! Yesterday it was full and proud, and today it’s a malformed, asymmetric straggler. Or is it a struggler? Pathetic fallacy! But O’Hara wouldn’t care as long as I ran with it:

here I am on the sidewalk

under the moonlike lamplight thinking how

precious moss is

so unique and greenly crushable if you can find it

Lightsey Darst is a writer, critic, and teacher based in Durham, NC.