Hanta Po: Lingering Spirits

George Slade reviews "Hanta Po--All You Out of My Way: Dick Bancroft--A Photographic Retrospective of the American Indian Movement," at Ancient Traders Gallery (1113 East Franklin Ave., Minneapolis) through July 9.

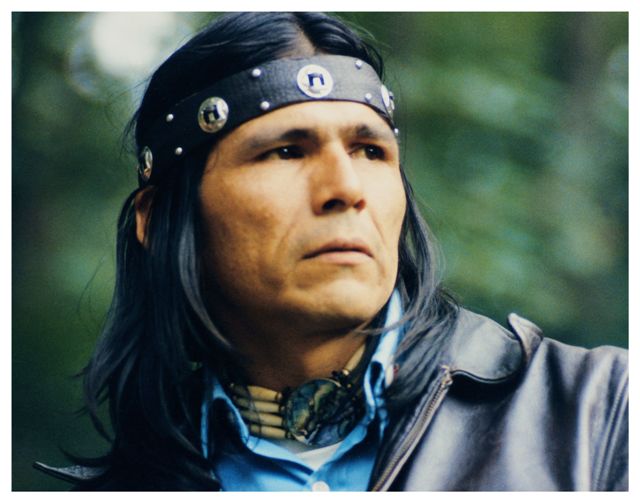

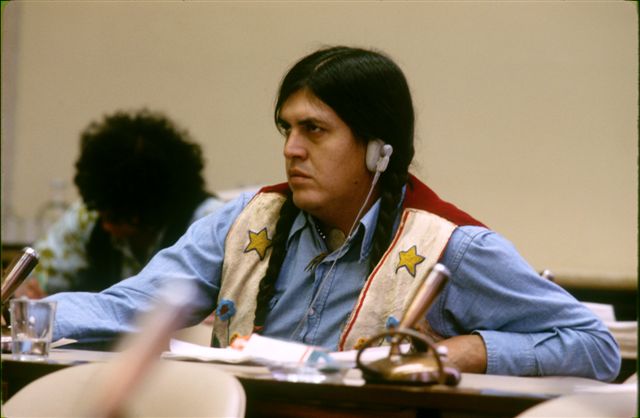

Dick Bancroft acknowledges that one reason he committed so much of his energy over the past 35 years to photographing Indians—from South and Central America as well as North America—was because of the strong personalities he encountered in their midst. The gusto, drive, wit, and charisma of leaders like Vernon and Clyde Bellecourt, William and Russell Means, Dennis Banks, and Leonard Peltier cemented Bancroft’s interest in serving history and telling the story of this fundamentally American encounter between dominant and indigenous cultures.

A major portion of Bancroft’s show at Ancient Traders consists of portraits: sometimes full bodies, sometimes heads seen close, so you can see skin texture, emotional expression, and souls as manifest in eyes. These eyes carry lots of weight—purpose, sadness, fury, and light. A poster in this show for a 1976 Paris exhibition of Warhol’s Indian portraits, with its estheticized, affectless face, nearly breaks the spell. (It’s Russell Means under all that Andy Warhol.) This poster, with its art-world coolness, is the qualitative antithesis of the broadsheets, logos, and banners from American Indian Movement and other Indian events in the Twin Cities and beyond that energize the gallery with the working, political spirit of the movement. The contrast between these two types of ancillary material underscores the life–versus-art discussion that comes up concerning photographic images: in this case, the conclusion compellingly favors the former.

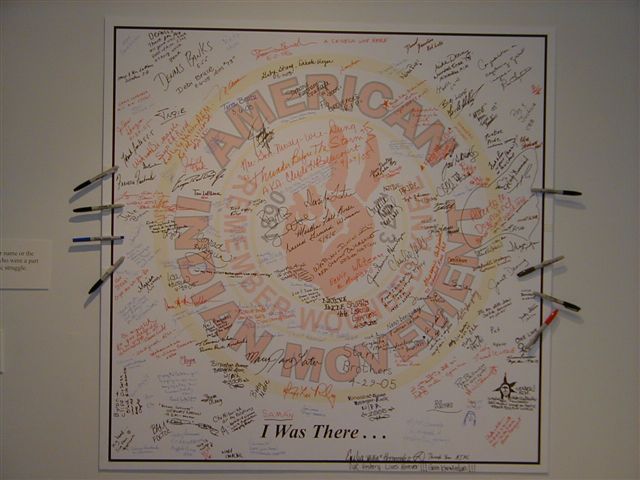

Every piece in this gallery—Bancroft’s images, the posters, loaned artifacts in cased displays—has a story behind it. Many visitors to the gallery bring their own stories, and gallery director Shirlee Stone has noted the tremendous desire of visitors to contribute to the largely unarchived body of first-person experience hinted at in these materials; a sign-in wall has been created, and will be added to when it runs out of room. This exhibition is a catalyst; it creates a focal point for a community’s collective memory. I hope that it prompts an enterprising organization to commit to serving as a central repository for this material, representing an organization (A.I.M.) that found its footing here in Minnesota.

One thing this exhibit is not intended to do is make money for Bancroft. His goal in photography, and life as a whole, has always been to serve the Indian community; he typically doesn’t print his work, preferring to communicate with slide presentations that carry the additional impact of his own narrative voice. A disclaimer in the show explains his thoughtful rationale about prints, and why he won’t sell them. The exhibition opening, with an ample, free banquet and an impressive line-up of speakers, underscored the social focus of the photographs; Bancroft, who is to date and may prove to be the only non-Indian ever to show work in Ancient Traders Gallery, was amply acknowledged but very much on the sidelines during this crowded, spirited event. He makes no claims to greatness as an artist, admitting only that he was lucky to be making photographs at a time when few other people were.

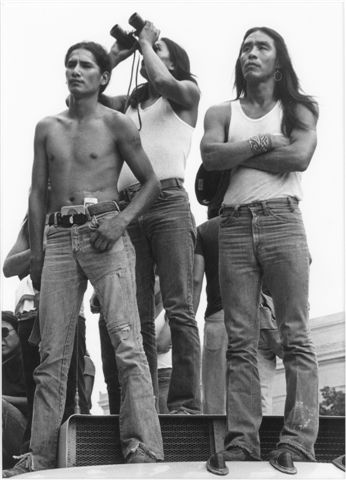

My own Bancroft-inspired story, characteristically, has to do with images. Many of the faces he’s recorded are familiar to me; they are clearer and truer in my personal experience than the romanticized, anachronistic figures populating the works of Edward Sheriff Curtis and other propagators of “noble savage” and “vanishing race” myths, the dominant images of native people within mainstream photographic history. I grew up with one of his images as a prominent element in my life; in their lake house my parents have long hung Bancroft’s 1981 poster announcing an exhibition of work from the 1978 Longest Walk cross-country march. (A copy of the poster is in the current exhibit.) The photograph (“Warriors”), used again as a poster image for the current show, features three stalwart, fierce young men standing atop a truck cab. It stuck in my mind as a modern, anti-mythic image of Indians, yes, but also as a symbol of masculinity, autonomy, and purpose.

I never saw that 1981 show, which took place in New York City, but at Ancient Traders there are over half-a-dozen photographs from the march, to flesh out the history and the spirit behind that trio. Reencountering this familiar image, I realize that I was as taken by this photograph as Bancroft was by the leaders he photographed. The figure on the left—scowling, torso-scarred, with a tooled leather belt, thumb hooked just so in his tattered jeans, and cigarettes (Kools, no less) tucked between the scar and the belt—I could scarcely imagine his life, but I admired him and his long-haired, defiantly arms-folded colleague (his brother, it seems). The third figure, a step back and gazing upward with binoculars, might have been me, an observer behind the front line. Or maybe that’s Dick Bancroft’s double, a powerful seer standing within the group.

As my commitment to photography grew through the 1980s I wondered about “Bannon,” credited in small type along the image. (I’ve realized since that using this nom de foto was self-protection during a time when involvement in “dissident” causes might attract unwanted attention from authorities.) This exhibit brings us all up to date on this provocative, empassioned, and too rarely exhibited body of work. Though Bancroft’s photographic touch is light, almost invisible, his images carry enormous social and historic weight. Their public presence is one of lingering spirits, a kind of conscience on paper that both recalls past actions and goads future ones. This is primary source material from an incompletely told history, shot through with deference to and admiration for the principal players.

“Hanta Po – All of You Out of My Way: Dick Bancroft – A Photographic Retrospective of the American Indian Movement,” at Ancient Traders Gallery, 1113 East Franklin Avenue, Minneapolis. Hours Wednesday through Saturday, Noon through 6 p.m.

Until July 9, 2005