When the Woods Come So Close

In the tradition of Robert Bly and, before him, Emerson and Thoreau, poet Tom Hennen offers up spare, luminous images drawn from the gnats and ants, frogs and toads, and all else he finds in "a narrow strip of woods."

ROBERT BLY CHANGED EVERYTHING FOR POETS IN MINNESOTA. He is our Whitman: He gave us confidence that our pines and prairies and plowed fields were a fit backdrop, even a fit subject, for poetry of the highest order. He encouraged us to speak plainly, to be clear and direct, to take risks. People talk a lot about “freedom.” Bly set us free.

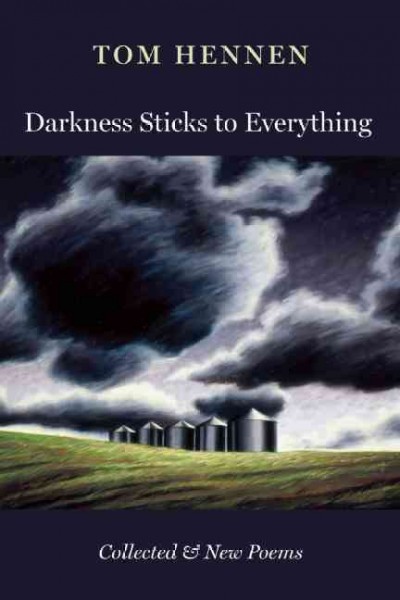

Tom Hennen’s new book from revered Copper Canyon Press, called Darkness Sticks to Everything: Collected and New Poems, is full of imagery born on a Minnesota farm and eternally alive in the human soul. To say the poems are indebted to Robert Bly is not to diminish the extraordinary achievement of this book. Hennen himself draws the connection: “Robert Bly: much help from the start, about 1963, and ever since,” he writes in his acknowledgments. Just glance at the table of contents: Titles such as “Smelling a Stone in the Middle of Winter” and “In Falling Snow at a Farm Auction” hint of the material Bly elevated to the level of great national literature in the groundbreaking Silence in the Snowy Fields (1962). Hennen turns close attention to gnats and ants, frogs and toads, thistles and aspen, and all he finds in “a narrow strip of woods.”

The modesty of these subjects, and this fidelity to the particular, are deeply American; long before Bly was born, Emerson and Thoreau made transcendence within nature a chief preoccupation of their writing.

Bly also championed, among many other things, a simplified diction — in part a turning away from academia, in part a movement toward authenticity. And you can see it in Hennen’s title: Darkness isn’t really sticky, like pine sap, but the idea is so appealing all the same, as is the sense that a child could have noticed and said these simple, deeply evocative words. There is innocence and freshness here, and immediacy.

We observe this throughout the book. These are the first few lines of “Smelling a Stone in the Middle of Winter.”

I can’t remember

What gravel and weeds are for.

This stone becomes important

And starts to act big.

I expect it to orbit the kitchen stove

Any minute now.

A stone does not “start to act big,” strictly speaking, and there are more complex ways and words to indicate size than “big.” But the unpretentious diction is winsome, as is the anthropomorphism. Is it out of fashion to regard stones as sentient? Yes, no doubt. For all we know, it’s also out of fashion in the literature of stones to regard people as sentient. Perhaps a cottonwood tree doesn’t “sing” because it is like a man, but rather a man sings because he is like a cottonwood tree. “Sing” is merely the human word for this phenomenon. To smell a stone: this engagement with our animal senses is the most important way we learn about the world, especially when we are children, when everything is new.

Also evident in these lines, and in many of Hennen’s poems, is the surrealism that entered American literature through Bly’s translations of Lorca and others. Under what conditions does a stone “orbit the kitchen stove”? André Breton said, “The man who can’t visualize a horse galloping on a tomato is an idiot.” In Hennen’s work, the imagination is intoxicatingly free.

***

One hallmark of a “new and collected” is a high degree of utility. Many of Hennen’s earlier collections are long out of print and unavailable, but here we have a generous selection from these rarities. Also, the vista across his books gives the reader an understanding of where Hennen began, where he traveled as a writer, and where he ended up. The earliest poems come from his 1974 chapbook, The Heron with No Business Sense, published almost forty years ago; that section in the new book begins with “Home Place.” The final poem in the book, called “Prairie Farmstead,” concludes with the words, “All is well”: between the first word and the last is a lifetime.

Once I saved a hummingbird that was trapped in a garage. I tried many things, but no stratagem worked, and finally the little bird was so exhausted that it slumped onto the garage windowsill, and I closed my hands around it and carried it outside. Then I opened them, and off it flew. Holding this book felt a little like that. It’s that vital. Emily Dickinson wanted to know, did her poems “breathe”? Does this book have wings?

__________________________________________________

Once I saved a hummingbird that was trapped in a garage. I tried many things, but no stratagem worked, and finally the little bird was so exhausted that it slumped onto the garage windowsill, and I closed my hands around it and carried it outside. Then I opened them, and off it flew. Holding this book felt a little like that. It’s that vital.

__________________________________________________

Like the poems of Mary Oliver, Hennen’s are seldom urban or even suburban. Like Ted Kooser’s, they are spare and filled with luminous images. Here is the poem, “Picking a World,” in full:

One world

Includes airplanes and power plants,

All the machinery that surrounds us.

The metallic odor that has entered words.

The other world waits

In the cold rain

That soaks the hours one by one

All through the night

When the woods come so close

You can hear them breathing like wet dogs.

It could not be clearer which world Hennen prefers. From Crawling out the Window (1997), the first of his books that consistently features prose poems, and language that is more relaxed, freer, here is a poem in full:

After Falling into the Slough in Early Spring

Back in the water, my clothes wet again. The loafing log I’m putting out for the ducks to rest on floats patiently near me. I stand there for a long time, so the teal start to swim close, a marsh wren tries to land on me, and the cricket frogs start up their calls that sound like pebbles hitting together. I scoop up one of the tiny frogs floating by on an old leaf and hold him just tight enough. His dark eyes have no fear in them. His body is no more than an inch long and brown as tobacco. I know I’ll never see him again once I let him go so I hold on a bit longer. If nature has a soul, this tiny frog could be the shape it takes. And if that soul makes a noise, it might sound like small stones being hit together.

It’s no wonder cultural conservatives scornfully claim that people like Tom Hennen are making a religion out of “environmentalism.” There is a sense here, shared by Thoreau, that the natural world is quite literally heavenly. Hennen says, “The thread that nature uses to connect all things together is joy.” And of strict rationality, he says, “Even answers that are right often make what they explain uninteresting.” In “Looking for Differences,” he asserts that “each thing on earth has its own soul, its own life, that each tree, each clod is filled with the mud of its own star.”

When my father was old, after a lifetime as a lawyer and judge and father of six, he suffered from a malady that kept him from walking without help. Once I was guiding him across a gravel parking lot, and he stopped suddenly. “There’s a beetle down there,” he explained. “I don’t want to step on him.” My father would have read these poems with sympathy and admiration.

***

It’s easy to be a little cynical about a guy who always knows the phase of the moon. We like our electronic devices, and we usually bring them everywhere we go. But there is no cell-phone reception in these pages. A certain ferocity is required to write poems this quiet, where your eyelashes freeze together because it actually is 30 below zero. The natural world is romantic, sure, and also brutal. The lives of zoo bears are much longer than those of the same species in the wild, and even Thoreau only lasted two years at Walden Pond, and then he worked at the family pencil factory.

The current preoccupation with “monetization,” though, is at minimum irrelevant in the company of these poems. Their loyalties are clear.

A fine introduction by Jim Harrison precedes the poems, and an afterward by Thomas R. Smith (including biographical information and wonderful insights into the work) concludes the book. Between these prose bookends is a body of work that keeps faith with the natural world and even becomes a part of it. Hennen says, “For the first time I understand/ I’m an animal too.”

Three Poems by Tom Hennen:

“Night near the Lake”

Rain began quietly with the dark.

Cold water

Soaks the fur of wild things.

A smell of wet lumber is everywhere.

The night sways slightly

Tied to the dock.

–From The Hole in the Landscape is Real, 1976

“Gnats”

The autumn smell of earthworms has attracted an off-course migrating woodcock who explodes like a feathery firecracker into the aspen thicket when I come too close. After all these nights of frost, most of the insects have given up for the year and have buried themselves in the duff. But here are tiny flies yet, small squadrons that dive and climb through the high reed grass. I don’t know how these dark-eyed gnats have survived the cold beginning of fall. Perhaps autumn has a back door left open to a summer afternoon in the world next to ours. –

–From Crawling Out the Window, 1997

“Plains Spadefoot Toad”

Toads are smarter than frogs. Like all of us who are not good-looking they have to rely on their wits. A woman around the beginning of the last century who was in love with frogs wrote a wonderful book on frogs and toads. In it she says if you place a frog and a toad on a table they will both hop. The toad will stop just at the table’s edge, but the frog with its smooth skin and pretty eyes will leap with all its beauty out into nothingness. I tried it out on my kitchen table and it is true. That may explain why toads live twice as long as frogs. Frogs are better at romance though. A pair of spring peepers were once observed whispering sweet nothings for thirty-four hours. Not by me. The toad and I have not moved.

–From Darkness Sticks to Everything, 2013

__________________________________________________

Related links and information:

Read the New York Times review of Darkness Sticks to Everything. Find out more about poet Tom Hennan and the new collection on the Copper Canyon Press website.

__________________________________________________

About the author: Connie Wanek is the author, most recently, of On Speaking Terms (Copper Canyon Press, 2010), which was a 2011 nominee for the Minnesota Book Award for Poetry. Her work has appeared in Poetry, Atlantic Monthly, Virginia Quarterly Review, Narrative, Poetry East, and many other publications and anthologies. She has been awarded several prizes, including the Jane Kenyon Poetry Prize and the Willow Poetry Prize, and she was named the 2009 George Morrison Artist of the Year. Poet Laureate Ted Kooser named her a 2006 Witter Bynner Fellow of the Library of Congress. Her poem, “Polygamy,” was the grand prize winner in the last iteration of mnartists.org’s What Light competition.