A Shuffling Game

Miranda Trimmier's perceptive essay reflects on the work in two McKnight Photo Fellowship exhibitions, both up through July 24, and on the peculiar "shuffling game" required to piece together a meaningful viewing experience out of such shows.

I ALMOST LEFT MIDWAY GALLERY AFTER KARL RASCHKE‘S OBFUSCATION. It was the first piece I saw, and I’d gotten a little lost in it, immersed myself in a way that seemed unfair to the other photographers in the 2010-2011 McKnight fellowship show, and to the 2009-2010 fellows, whose work, mounted at Franklin Art Works, I was supposed to view next. All told, I’m sure I spent at least a half hour with the work, sprawled on the floor listening to Obfuscation Soundtrack (a audio mixture of interviews, crowd tracks, and play-by-plays from Raschke’s father’s career as a professional wrestler), and shuffling through the photos sitting loose in two boxes on a table at the middle of the gallery. Raschke left the two boxes — full of pictures of his father and family, but also of more random images, of brick walls, wild turkeys, and football fields — for viewers to sift and arrange as they please. I started making groupings of kids, in part because I couldn’t stop thinking about something Raschke’s sister had said about her father’s job, in an interview on the Soundtrack. Her childhood was pretty normal, she insisted, except sometimes she’d “come home to four midgets smoking cigars on the couch.” Soon, though, I began placing photos together for less narrative reasons: for a shared geometry between window panes, or a common shade of green. The shuffling of photos echoed in the gallery as I created another configuration, and another. I’d become blissfully lost, as one does with an interesting piece of art.

But I didn’t want to be lost. I’ve read Diane Mullin’s 2010 essay about fellowship exhibitions like the McKnight and sympathize with her concern about their lack of unifying themes, which, she points out, can be frustrating for the exhibiting artists, whose work is thrown next to pieces with which it might share very little, and for audiences, who have to make sense of a gallery full of disconnected pieces. I also read Mary Abbe’s review of the current McKnight photography shows, and it seems like a perfect illustration of Mullin’s point. Her full-page article in the Star Tribune devotes nearly half its words to a single artist, splitting the other half of the article, in laundry-list style, between the remaining seven artists; a couple of them get only a single passing sentence. If this imbalance feels unfair to the artists, it also seems to describe a fragmented, unsatisfying viewing experience.

And so, I almost gave up after Obfuscation; I’d spent too much time with it, I felt, to be able to switch gears and deal with the other three sets of work left in the gallery, let alone the four more waiting for me at Franklin Art Works. But on my path to the exit, I stopped, for some reason, in front of one of Amy Eckert‘s collage pieces, a shot of rippling water set next to a close-up image of a mattress distorted into the shape of a wave. She seemed to be playing a shuffling game rather similar to the one I’d just been playing with Raschke’s images — mixing objects and textures, looking for unexpected webs of affinities. According to her artist statement, she’s interested in the way these juxtapositions create “moments of connection and dislocation for the viewer.” Eckert might have pushed the game further, though, and made the combinations stranger by tinkering with scale or focus. And yet I appreciated her spirit of her experimentation — I’d spent ten minutes tracing a repeated red line through a batch of Raschke’s photos, after all — and her work inspired me to keep moving through Midway, with this playfulness in mind.

Across the gallery, Gina Dabrowski‘s photos offered an unexpected complement to Eckert’s collages. Though her work and Eckert’s look completely different and grow out of separate objectives, they share a formal interest in the play between man-made and natural objects. Dabrowski, in particular, has a nuanced take on what this relationship can be. She begins with an interest in the fate of garbage, which brings her to an abandoned dumping ground. Underbrush and trees have begun to grow up through the heaps of trash: old leather shoes and broken plastic and the rusted skeletons of machines. The images are unexpectedly powerful, and not simply because they’re gross or beautiful — they’re a bit of both — but because Dabrowski catches man-made materials looking surprisingly organic. Standing in front of her photos, that slippage made me feel as though I was watching these discarded objects reveal qualities that exceeded their relationships to humans, qualities made visible only by the passage of time.

It was easy to follow this train of thought to Chuck Avery‘s work, hung on the wall adjacent to Dabrowski’s. He also explores the action of time on human objects, but he’s interested in the ways we try to preserve them, and the ways these acts of preservation connect to the stories we tell about ourselves. His images come from historical centers, particularly those focused on American culture. The photos are full of recognizable tropes of U.S. national identity: Native American tools and pieces of frontier artifacts, noble astronauts, and the articles of war. At his best, Avery layers the references in ways that at once tell their many stories and question them. In one image, a model oil rig stands in a display case, through which a viewer sees a collection of old gasoline pumps painted with the triumphant logos of long-defunct gas companies: a big red crown, a soaring eagle. On the front of the display case a viewer can see the faint reflections of other photos, and of a human hand. One can form stories about labor, or marketing, or popular culture, depending on how you choose to sift through the photo’s layers.

______________________________________________________

I no longer worried about mentally managing all the different fellowship projects; there was pleasure in the shuffling game. So, I hopped on my bike and steered it towards Franklin Art Works, with Raschke, Eckert, Dabrowski, and Avery’s images, all arranging and rearranging themselves in my mind.

______________________________________________________

IN THIS WAY, I INTUITED A PATH THROUGH MIDWAY. I no longer worried about mentally managing all the different fellowship projects; there was pleasure in the shuffling game I’d learned from Raschke. So, I hopped on my bike and steered it towards Franklin Art Works, with Raschke, Eckert, Dabrowski, and Avery’s images, all arranging and rearranging themselves in my mind.

The shuffle was becoming so natural, in fact, that by the time I got to Franklin and began perusing Carrie Thompson‘s photo book, GOMA, I didn’t even try to start at the beginning, just dove into the middle and flipped around from there. I’d been tracking the reoccurrence of rabbits and fur through the book before I realized that GOMA was, in fact, the name of a rabbit, the first photographic subject Thompson seized onto during a trip to Japan. And yet I didn’t feel as though I’d done the book a disservice by starting in the middle, though it does chart something of a story, including the progression of Thompson’s pregnancy. The arrangement of images is elliptical, friendly to skimming and wheeling back, and suggesting something intriguing about the way ideas develop — slowly, unconsciously, and, in the words of Amy Eckert, through “moments of connection and dislocation.”

Lex Thompson, too, develops his ideas in this loping, elliptical manner. Thompson mixes his own photos from a trip to Hawaii with clichéd images from movies and tourist campaigns. Some of his photos specifically reference these clichés, examining the way they interact with day-to-day Hawaii: the incongruity of a poster of a hula girl hung in a skating rink, or the sadness a tropical mosaic takes on in a dirty, abandoned building. Others fill in the clichés’ blind spots, the things that are hard to imagine alongside surfers and purple flowered leis. One especially compelling photo documents a strange rocky overhang. The top is tangled with trees, weeds, and mud, and its underside creates a dank cave-like opening. It’s a spooky, fecund space, and one that’s difficult to reconcile with our popular imagining of Hawaii.

Paul Shambroom‘s photos, set facing Lex Thompson’s, could easily have been at home at Midway, positioned between Gina Dabrowski’s and Chuck Avery’s. He documents the fate of decommissioned war artillery, and the old weapons he found lead a second life somewhere between preservation and the dump. They’ve been saved and displayed, but in isolated, small-town spots: near churches, next to parking lots, in empty fields. One gathers that Shambroom is interested both in the incongruity of artillery placed in the middle of everyday small-town building and objects, and in the way these things are more closely related than we usually acknowledge. He composes this church photo, for instance, by fixing its white steeple in near-perfect symmetry with the white tip of a decommissioned missile, which is also reflected in a puddle in the church parking lot.

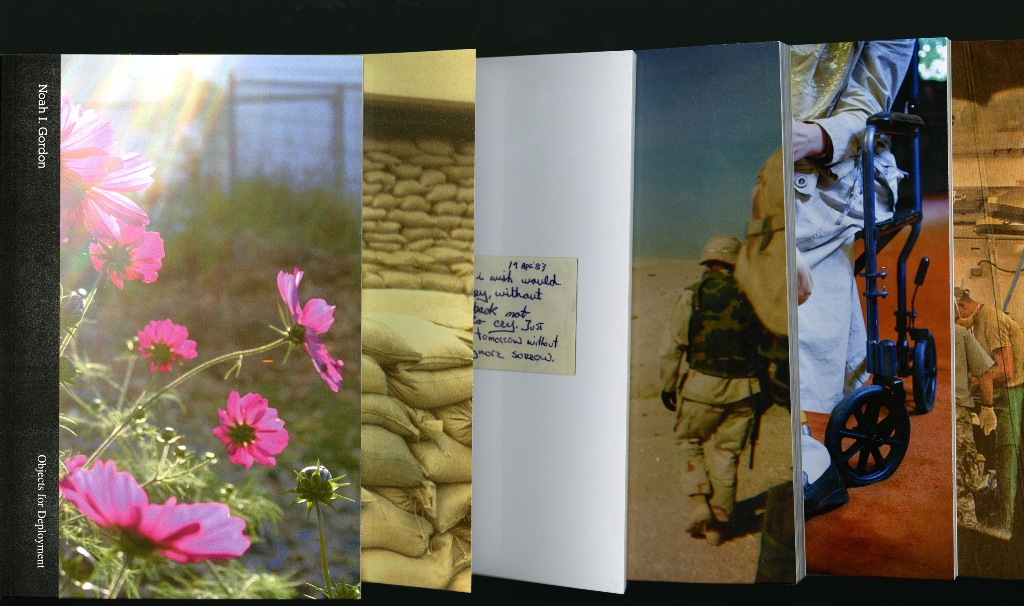

Though that point is a little heavy-handed, Shambroom’s images also sit well beside Monica Haller’s, who spent her McKnight fellowship year in ambitious collaboration with Vietnam and Iraq war veterans. Haller developed a software program that allowed the vets, whom she’d been interviewing and working with, to plug their own photos and text into a basic book template. The results elaborate upon, in more human terms, Shambroom’s question about the relationship between war and everyday life. One book in the exhibition documents an Iraqi civilian’s fight with the U.S. government to get a decent set of prosthetic legs after her home was accidentally bombed by U.S. troops. Another explains the role photography comes to play in a Vietnam vet’s struggle to make sense of his combat time; a third follows a young Iraq war who’s also trying to make sense of his wartime experience, but coming up with a more ambivalent set of answers. He doesn’t really know what to do with himself now that he’s home, he reports:

I keep on the move.

I have been back for over 6 years and I can’t wait to get back on the road. I keep looking for something comfortable[…].

I want to know who I am.

I want you to know what I have done.

I want you to know what it has done to me.

I want you to know what it has done to us.

I have to confess that my shuffling game broke down here. I no longer had interest in following red lines, finding shared artistic strategies, or stitching together moments of connection and dislocation. I just wanted to sit with these books and give them my full concentration, without the intrusion of other photos and artists’ ideas.

No, I wanted to come back and start over completely, to give Haller’s project the benefit of a fresh set of eyes.

And so, Mullin’s concern about such exhibitions came cycling back, and with renewed power. Yet I can still see the special opportunity afforded by the fragmented fellowship show structure. There is always a conceptual through-line to be found, and even at its most tenuous and arbitrary, it can supplement an artist’s work in surprising and satisfying ways.

An astute viewer, though, will know this game’s limits, know when it’s time to stop shuffling and give a body of work a different kind of attention.

______________________________________________________

Related events and exhibition details:

Exhibitions for the 2009-2010 and 2010-2011 McKnight Artist Fellows for Photography at Franklin Art Works and Midway Contemporary Art respectively. Franklin Art Works is exhibiting recent work from 2009-2010 fellows Monica Haller, Paul Shambroom, Lex Thompson and Carrie Thompson; Midway Contemporary Art is exhibiting recent work from 2010-2011 fellows Chuck Avery, Amy Eckert, Gina Dabrowski and Karl Raschke. Both shows are on view through July 24. Find links and additional information about the artists and exhibitions in the calendar listing for the McKnight Photography Fellows’ shows on mnartists.org.

There is an artist talk with McKnight fellows Carrie Thompson, Monica Haller, Karl Raschke, and Amy Eckert at the Walker Art Center (Cinema), Thursday, July 7 at 7 pm. Admission is FREE.

______________________________________________________

About the author: Miranda Trimmier spends a lot of time reading, writing, and making things.