Musings on “World-Premiere, Full-Length” Ballet in Twin Cities Art and Culture

Dance critic Camille LeFevre weighs in on what makes for truly extraordinary big-ticket ballet, and specifically, on the latest world premiere at Northrop, "Moulin Rouge" by the Royal Winnipeg Ballet.

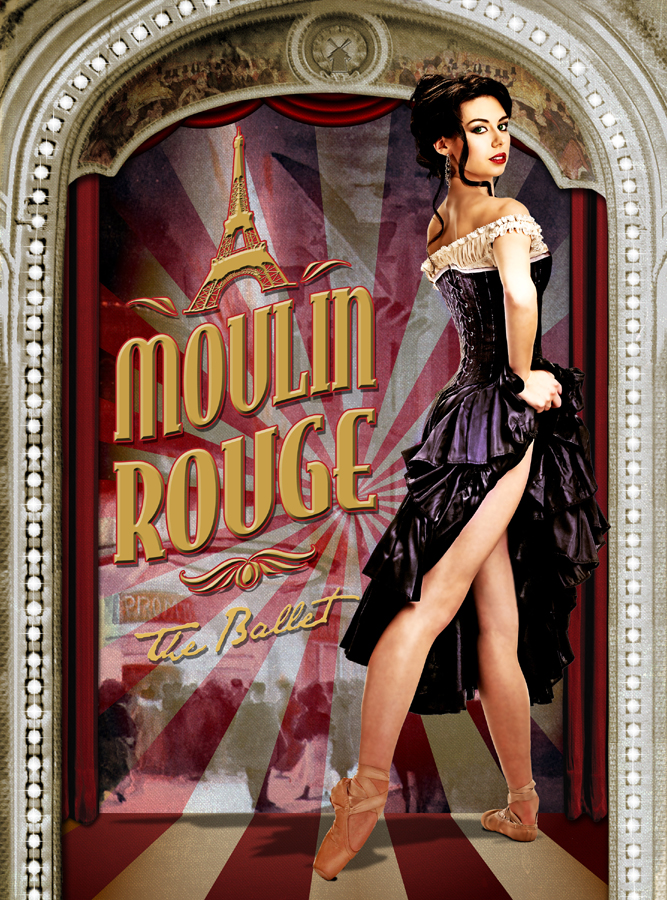

WORLD PREMIERES OF DANCE WORKS HAPPEN ALL THE TIME in the Twin Cities. In October alone, Ragamala Dance premiered Dhvee; Ballet of the Dolls, Pas de Quatre; Stuart Pimsler Dance & Theater, Tales from the Book of Longing; and James Sewell Ballet, The Bad Plus Us. None of these world premieres, however, were of original, full-length, story ballets. That rarity, and the hype that attends such an event, belonged to Moulin Rouge: The Ballet, performed by the Royal Winnipeg Ballet (RWB).

Clocking in at two hours and 10 minutes, with two acts and an intermission, the large-scale production had its world premiere at Northrop on October 17. Based on a traditional, classical romance about a doomed couple (Nathalie a dancer, Matthew a painter) and set in and around an elaborate set that conjured the environs of the famed Paris cabaret, Moulin Rouge offered up a fairly enjoyable evening of entertainment if you could look past the clichés. But a few aspects of the performance — a tendency toward a bland similarity among the main male characters, all of whom danced alike; the odd choice of an extremely thin, pale, pink girl to be the star of the colorful, lusty, bawdy Moulin Rouge — kept the ballet from being extraordinary.

Aside from a nearly full auditorium of 4,000 audience members, who concluded their experience with a standing ovation — and there’s no disputing those numbers nor that many of those brave souls may have been newbies to dance — is it truly enough for a production like this to be merely enjoyable and entertaining? It’s a particularly relevant question when you consider that, as was suggested in media previews of the performance, RWB is looking to forge a relationship with Northrop. Apparently, after last year’s performance of Mauricio Wainrot’s Carmina Burana (a lackluster affair, as many of the dancers appeared to be marking the choreography, rather than dancing it), Northrop director Ben Johnson and the RWB began negotiations about premiering Moulin Rouge here. Who courted whom exactly, isn’t clear; but if RWB is hoping to perform at Northrop on a regular basis, is this what we might expect? And more to the point, don’t we deserve better?

RWB is popular in Canada, especially for its populist versions of iconic stories like Peter Pan, Cinderella, and Dracula. (And, yes, they also perform a version of The Nutcracker.) Jorden Morris, a former RWB principal dancer, may be a “Canadian superstar choreographer,” as Johnson enthused in the Moulin Rouge program: Morris’s claim to fame is Peter Pan, reportedly RWB’s biggest box-office success. But, really, Twin Cities audiences are not that provincial. After all, Mikhail Baryshnikov and Mark Morris premiered their White Oak Dance Project at Northrop; Bill T. Jones premiered a version of Still/Here. Now, those are superstar choreographers: Jones creates tough, challenging work; Mark Morris is the eternal golden boy of entertaining and masterful choreographic invention.

For Moulin Rouge, Jorden Morris delivered spectacle, to be sure. The scrims and curtains were painted with Parisian street scenes, the elaborate sets were fabricated to resemble stone staircases and towers, the lighting was cinematic — the shadow of the windmill (moulin) turning in some scenes was a particularly nice touch, and the windmill paddles, outlined in blue neon lights, glammed up the sets. One tango scene ended with a full-blown Broadway blowout of black foreground and red lights. The women’s costumes were frilly, frothy, and, for the most part, vibrantly colored. The Canadian group, Quartetto Gelato (accordion, cello, violin, oboe), performed live as street musicians — a lovely, authentic touch. The taped music, on the other hand, was a sometimes-odd blend of Debussy, Strauss, Offenbach, and French accordion tunes. (Strangely, neither the music nor the musicians were credited in the program.)

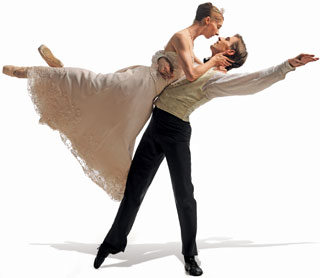

The ballet’s story includes romance, a love triangle, possession, violence, and death, with emotions, in this production, communicated largely through broad gestures and pantomime. Morris’s choreography consists of classical ballet, mixed with some can-can and tango — safe and rather ordinary choices, but performed by the dancers with technical acuity. While the tango generates kinetic heat in some of the scenes, the style’s use in this ballet, and for this narrative, is perplexing. Some actual passion — and not just the pantomimed sort — between characters would have deepened the dramatic possibilities of the ballet. Now, about those characters.

______________________________________________________

Lawson emerges from her special tower as the cabaret’s new can-can girl, costumed not in a vivid confection of robust sexuality, but in a diaphanous pale-pink gown and, god help us, wearing a tiara. It’s the ballerina-as-helpless-princess trope once again.

______________________________________________________

The ballet has three male principals: The iconic painter, Toulouse-Lautrec (Yosuke Mino); the novice painter, Matthew (Gael Lambiotte), who falls in love with Nathalie (Vanessa Lawson); and the nefarious owner of the Moulin Rouge, Zidler (Jamie Vargas), who becomes Matthew’s romantic rival. The problem is that the choreography and characterizations for these three are nearly indistinguishable from one another. (I could tell them apart, primarily, by their costumes.) Now, this uniformity could be a deliberate move, on Morris’s part — a mirroring device. As romantic rivals, Matthew and Zidler push each other, leap across each other’s space, and pull and twirl the girl with the same intensity and choreographic measure. Similarly, the movements of Toulouse-Lautrec and Matthew — both painters — are often performed in unison, as reflections of each other.

An exception: When Toulouse-Lautrec takes Matthew to the tailor, a bevy of tall, pointy assistants, bearing tape measures and swatches of cloth, magically dress the younger painter in new garb. (The mice making Cinderella’s ball gown in the Disney movie, anyone?) But aside from this paternal, relational gesture, the painters are rendered on stage in largely the same way. The mirroring continues when the two face off, Western style, with paintbrushes instead of six-shooters, and twirl the model atop her pedestal (recalling the familiar image of a ballerina revolving atop a music box), getting into position for an easel duel in which, again, their movements are closely aligned.

Yes, parts of Moulin Rouge have a distinctly “where-have-I-seen-that-before?” kind of resonance. American in Paris came to mind as the teeny, toothpick-limbed Lawson took the stage, recalling a diminutive version of the ingénue Leslie Caron to Lambiotte’s sturdy, soaring Gene Kelly. The romantic pas de deux between the leads is full of high lifts, pulling away and gathering together, and delicate loveliness — a romantic ballet cliché. And, lest we forget that Moulin Rouge is a ballet, the biggest cliché of all is dragged out: Lawson emerges from her special tower as the cabaret’s new can-can girl, costumed not in a vivid confection of robust sexuality, but in a diaphanous pale-pink gown that emphasizes her floaty, ethereal movements across the stage. And, God help us, she’s wearing a tiara. It’s the ballerina-as-helpless-princess trope once again.

To her credit, Lawson’s strings of pirouettes and fouettes elicited rounds of applause. The audience also spontaneously clapped at the first strains of the famous can-can music, while the dancers, their height and legs lengthened by performing en pointe, repeated the signature phrase of steps and kicks that ended with shaking the ruffles on their bums. Entertaining? Certainly. Enlightening or extraordinary? No.

To be fair, Johnson’s first season as Northrop’s dance curator has already proven to provide something for everyone. For the hardcore dance aficionado — the people who like their choreography rigorous, inventive, provocative, and their movement both kinetically and intellectually tantalizing — Random Dance was the ticket. For folk-dance followers — and they are legion — Virsky set them afire with an unforgettable evening of choreographic pyrotechnics.

And, in Moulin Rouge, ballet fans received a dazzling spectacle; the work, as previously mentioned, received a standing ovation. This was, after all, a world premiere that, for the most part, was as easy on the eye as it was to digest. But, really, I do believe we deserve better. A world premiere by Christopher Wheeldon and his company Morphosis, or anything performed by American Ballet Theatre or New York City Ballet (which used to perform regularly at Northrop) — then, we’d be talking superstar choreographers and entertaining, evocative, enlightening, truly extraordinary ballet.

______________________________________________________

About the author: Camille LeFevre is a Twin Cities arts journalist, dance critic and college professor. Thanks to John Munger for the intermission chat!