Zoe Cinel: Sharing and Healing

A conversation with the 2023/24 MCAD–Jerome Fellow on their practice of addressing chronic illness through holding and creating space for individual and community healing

MELANIE PANKAUYou describe yourself as an interdisciplinary artist. In your practice, you work across mediums, from mixed-media soft sculptures, audio storytelling, video installations to community conversations. I’m curious if you could talk about your relationship of working with these different mediums and what do you want them to communicate to the viewer?

Zoe CinelWe all learn in unique ways, and we navigate the world differently. Our experience of the same thing is rooted in our identity, values, positionality within society and history. Perhaps because I studied design as an undergraduate student, and that training emphasized the importance of communication and “user experience,” I approach materials from a conceptual standpoint: what medium can speak of a certain theme and evoke a feeling? As an example, for LESS IS ENOUGH (2023), a solo exhibition at Second Shift Studio, I created artworks with completely different media, tied together by common themes, recurring elements, and with components that built off of each other.

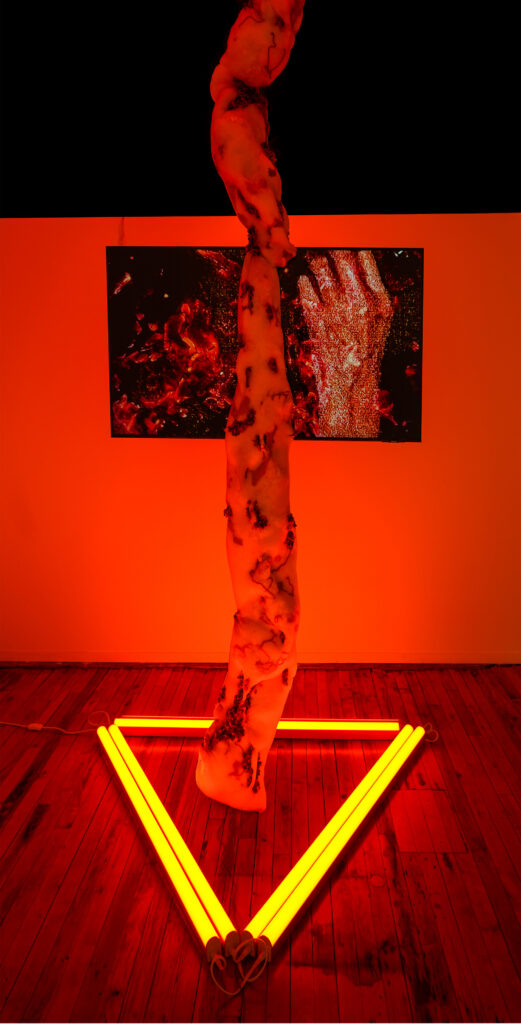

Self-portrait with flare (2023) was a multimedia installation composed of a monitor that was playing a short movie about autoimmunity and generational trauma, a soft sculpture sculpture made of tulle fabric, pillow stuffing, plastic, yarn, velvet, glitter glue, two mannequin arms, chain that split the monitor in two, and a series of shop lights casting a red light over the sculpture. The sculpture and red lights visualized the experience of having a flare of Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA), where joints–especially hands–become red, swollen, hot. In the video is an animated collage of my medical images, text about RA, and family pictures showing my grandmother’s hands deformed by RA.

Hands and softness are also present in Rest With Me (2023), a resting space made of three pillows and a mattress, created in collaboration with Gretchen Gasterland-Gustaffson. We used a repurposed donated hospital mattress, fabric and pillow stuffing, and cyanotype prints. This project was inspired by Carolyn Lazard’s interventions on the benches of the Walker Art Center for their solo show Long Take (2022). The main drive was to create a welcoming and soft place for the body and the mind: on the “arms” of the hugging pillows we hand-stitched patches made of cyanotype fabric with quotes from participants of another ongoing project, Conversations about care. The messages are sometimes comforting–”Care is in the details”–sometimes inspiring and challenging–”Urgency is false.”

Ideas of comfort and softness are present in the photo series “Natura Morta with” (2022–ongoing). Arrangements of moldy, dried flowers and my used medications sit on gray pillows. This work captures the intersection of beauty and decay as a quest for accepting to learn from a body that is ill and not perfect, yet entitled to comfort and visibility.

“I am still highly suspicious of the biometrical industrial complex. Over the past few years, I have found myself completely and inextricably tied to this world in a way that I didn’t want to be. I desire an alternative and I still believe that one day I won’t need this medication to live. Yet, currently, I’m fully dependent on Humira for my functionality. It is difficult to conceive of resistance to something that I need right now.” –Carolyn Lazard, How to be a Person in the Age of Autoimmunity, 2013.

MPIn your community engagement work, you have created spaces that are both celebratory and cathartic for marginalized bodies to share their experiences. You have expressed that you strive to produce social change. Could you share more about how you hold space for others and what changes have you seen or experiences through these events?

ZCWhen I was diagnosed, I was immersed in a completely ableist lifestyle and didn’t have a clue about self-care. That was highly influenced by the demands of the O1-B visa process, but also I am a Capricorn… When, later, I realized that spoons (Christine Miserandino, Spoon Theory, 2003) were scarce for me, as a chronically ill artist, I had to unlearn all of that, and I still am. Find a new community to identify with, and re-build that sense of self disrupted by autoimmunity.

I did this by holding spaces for others because I believe that sharing knowledge benefits us all and builds resilience. So projects like Conversations about care (2022–ongoing) originated as a response to the void of not having a space process my own trauma. In this series of participatory events, people gather to read books about care and share their perspectives. The design of the space is particularly important as I strive to make it accessible, adaptable, and comfortable for anyone who signs up: there is soft seating, hot tea, snacks that consider different food allergies and sensitivities, adjustable lighting, a scent-free environment, and handmade Heating Pads (2022–ongoing). Masking is encouraged although not required as some participants might need to lipread or have other health needs regarding masking. I try to approach accessibility as an adaptable practice, encouraging participants to discuss and agree on what actually feels comfortable and safe for the group at the beginning of each conversation. Past events were held at Second Shift Studio, New Arab American Theater Works, and the MCAD MFA building; upcoming ones will take place virtually on Zoom May 4th and in-person at Fresh Eye Gallery on June 25th (info and link to the registration form on my website).

I think holding space was an intuitive response to the void because of my activist background and attitude toward collaboration. Since 2018, I have learned about cross-cultural forms of hospitality and inclusion by working closely with amazing artists like Aki Shibata, Peng Wu, Preston Drum, and Shun Yong through CarryOn Homes, and by assisting mentors like Pramila Vasudevan in projects like the Parking Ramp Project (2018). More recently, my involvement with the disability justice community exhibition team affiliated with AmplifyMN: A Disability Justice Collective is teaching me greatly about accessibility. I am excited for our upcoming project: a group exhibition celebrating disability justice in Minnesota now, and opening at the Mill City Museum in July. I want to thank Mai Thor, Poppy Jean Sundquist, Gereon Fuller, Alison Bergblom Johnson, Chukwuma Udezeh, Jessica Cooley and AmplifyMN: A Disability Justice Collective for this opportunity to be in conversation with them all.

MPYour work spans from self-portraiture to larger communal experiences of navigating the healthcare system. How do these vulnerable, intimate, and challenging moments of caring for the body unfold your work?

ZCIn a broad sense it’s through visibility and invitation. Although illness is a universal human experience, we are socialized to keep it private. It’s an uncomfortable topic but this stigma is just a construct created by capitalism. It perpetuates isolation; it’s harmful.

It seems that opening up about my experience invites others (mostly) to respond with vulnerability. It’s in that space of connection that we can develop language and practices to care for ourselves and each other.

An example of how visibility plays into some of my projects is the multimedia installation Ode to My Medical Bills (2021), where five monitors play a series of video collages including also my x-rays, MRIs, and other inner body images. The monitors intersect two custom-built sheetrocked walls and are split by it: a monument to feeling overwhelmed and othered from my self as I went through my diagnosis. I like to work with this “archive” of images of my body as a way to reconcile with the scrutiny by the medical gaze, and humanize these internal, invisible parts of my body.

“When you have cancer you disappear, only to be replaced by something else: a patient. This is a strange being, on the one hand, entirely made of data: blood exams, images of body parts, lab values, diagnoses—the list goes on. But, on the other hand, this data is not simply you: it barely approximates the full complexity of selfhood.” –Alessandro Delfanti and Salvatore Iaconesi, Open Source Cancer. Brain Scans and the Rituality of Biodigital Data Sharing, 2016.

MPWhat does comfort and self-care look and feel like to you?

ZCSelf-care is a newish journey for me. One born from awareness, grief, and practice. My autoimmune diagnosis served as a wake-up call, urging me to explore the very concept of self-care. Healing required confronting the roots of my illness, learning to relate to it rather than react. This journey of self-discovery wasn’t about a predefined path, but rather one I began after recognizing the connections: autoimmunity linked to generational trauma, mental health struggles tied to the O1-B immigration process, and burnout fueled by the pressures of capitalism.

Also, self-care, I realized, extended beyond the individual. It became a social responsibility–a way to honor ancestral wisdom, care for the environment, and nurture the well-being of those around me, both near and far.

In my daily routine self-care manifests as: ginger tea after a meal, nettle tea before bed, walking instead of driving whenever possible, overtone singing when my nervous system is overwhelmed. It also helps me to invest in necessary utilitarian objects, like heating pads, with actual healing power by creating my own.

In 2022, during an RA flare, I started paying attention to the objects I carried with me for managing the unmanageable: a cohort of painkillers, anti-inflammatory lotions, pillows, braces, herbal remedies, and heating pads. As I was shopping for a new microwavable heating pad, I noticed the impersonal, standardized, mute, sad look of most of these objects. It reinforced the stigma in a way: illness is pale gray, blue, or green. Let’s keep it invisible so we can feel it’s contained. In response to my depressing and illuminating shopping session, I started creating my own Heating Pads from repurposed fabrics: old socks, hats, shirts, etc. Although I haven’t worn these clothes in a while, I have kept them in a drawer because they meant something to me: a sweet gift, a caring memory, a dear person who is geographically far away. Each heating pad is unique and has unusual shapes: a pair of shorts, a long wrap made of socks, a shirt that shrunk in the drier. They adapt to different bodies and various body parts. Their DIY look speaks to the messy-yet-creative process of giving and receiving care.

MPWhen talking about your work, you mentioned that “Illness doesn’t happen in a vacuum.” Can you tell us more about how this statement informs your practice or a particular project.

zcThis is a large topic that I could summarize by saying that we live in a capitalistic society built upon exploiting bodies and natural resources. Perpetual extraction is simply not sustainable. So when the sources of our sustenance, water, air, and relationships, are themselves poisoned, it’s not a surprise that our bodies become ill and react to a global state of emergency.

In the microcosm of my artistic practice, the installation Self-portrait with flare (2023) explores this idea of interconnectedness by looking back at the potential roots of my illness as it traveled through DNA, environment, and time. When in 2020 I was first diagnosed with RA, I wondered where this came from–why now? Illness became evident and diagnosable around the time that I went through a traumatic visa rejection and the spread of COVID-19 became a pandemic. Definitely a charged time that took a toll on a body that was already most likely charged with carrying around traces of generational trauma.

Self-portrait with flare contains a video that brings together family pictures showing my grandmother’s hands and x-rays of my hand bones taken in 2020. I remember my grandmother’s hands caressing my face as a kid. It was a familiar and uncomfortable feeling: her fingers were frozen into a claw, bones sticking out of each joint, hard like marbles. She was able to grab, but her fingers were never straight. Linda, that was her name, was a teenager during the Second World War when she lost a brother to the nazis: her family lived on the Gothic Line, a military border that lasted throughout the entirety of the war. She married a partisan, an anti-nazi hero, and ended up raising two children as a widow when he died of cancer at a young age. She could make beautiful bags that she sold for modest prices to fancy tourist shops in Florence, Italy.

I often think about her life and I wonder if this illness that has traveled through generations has something to do with the trauma of growing up in a war zone. If, as Susan Sontag states, “illness is a metaphor,” RA is one of battlefields, chaos, and overlapping narratives. I think of all the pain she endured while her hands crunched into their form and of my privileged, but taxing, access to chemicals that keep mine straight. So to me, illness made me look closer at family history and society. I truly cherish the learning and unlearning that illness has brought to me, including the understanding that there is no binary division: we are all ill and well at times. The knowledge gained around living with illness is precious and should be publicly shared for collective healing.

“Chronic illness involves a recognition of the worlds of pain and suffering, possibly even of death, which are normally only seen as distant possibilities or the plight of others (..) the development of a chronic illness like rheumatoid arthritis is most usefully regarded as a ‘critical situation’, a form of biographical disruption.” –Michael Bury, Chronic Illness As Biographical Disruption. Sociology of Health & Illness, 1982.

MPWhat artists, writers, thinkers are inspiring you right now? And why?

ZCAlternative paths for healing outside of the realm of western medicine are a main area of research for me right now. When western science tells you your illness isn’t curable and can provide only chemicals for management, I was like, “let’s find care elsewhere, thanks!” Although I am privileged and grateful to have access to that kind of medicine, illness doesn’t just affect the body but my whole sense of self.

So I have been looking into more cultures of healing and care. I am listening to Indigenous Medicine Stories: Anishinaabe mshkiki nwii-dbaaddaan, hosted by Dr. Darrel Manitowabthat. This podcast educates about Indigenous healing and the use of storytelling as medicine, which deeply resonates with me. I have also been reading about the history of witches, herbalists, midwives, healers, and their social role in pre-medical society. As a visual artist, it’s been a revolution to learn about the impact of visual representation and folk narratives in our general perception of illness, disability, and the body today. I recommend reading Amana Leduc’s Disfigured: On Fairy Tales, Disability, and Making Space, and Witches, Midwives, and Nurses: A History of Women Healers by Barbara Ehrenreich.

Other artists and authors who work within the frame of disability justice, crip advocacy, and activism whom I look up to are Alice Wong, Carolyn Lazard, Lauryn Youden, Salvatore Iaconesi, Oriana Persico, and Johanna Hedva, just to mention a few.

MPWhat has winning the MCAD–Jerome fellowship meant to you?

ZCIt has felt very special as I remember helping some of the past fellows install their work when I was a Graduate Assistant with the MCAD Gallery. My years at MCAD were formative and full of discoveries, it’s a bit like a homecoming to exhibit here again… and I like the challenge of the non-traditional architecture of this gallery, with its open spaces, unusual corners, and such. Having access to resources–like printing shops, wood shops, digital equipment–that support my interdisciplinary practice is invaluable. And last but not least, this year’s cohort is wonderful: Leeya, Prerna, and Ziba… there is an interesting overlap of themes and lived experiences, a resonance that transpires from very distinct practices and visual approaches. And a great energy when we meet as a cohort. I feel this experience is feeding me as an artist beyond the productive aspect of the work.

MPIf you could describe your work in one word, what would it be?

ZCDense.