Zoom In: Michael Thomsen

Susannah Schouweiler talks with artist Michael Thomsen about the enduring lure of the circus and how his first job as a kid, sorting through junk drawers of the recently deceased, left its mark on his artwork.

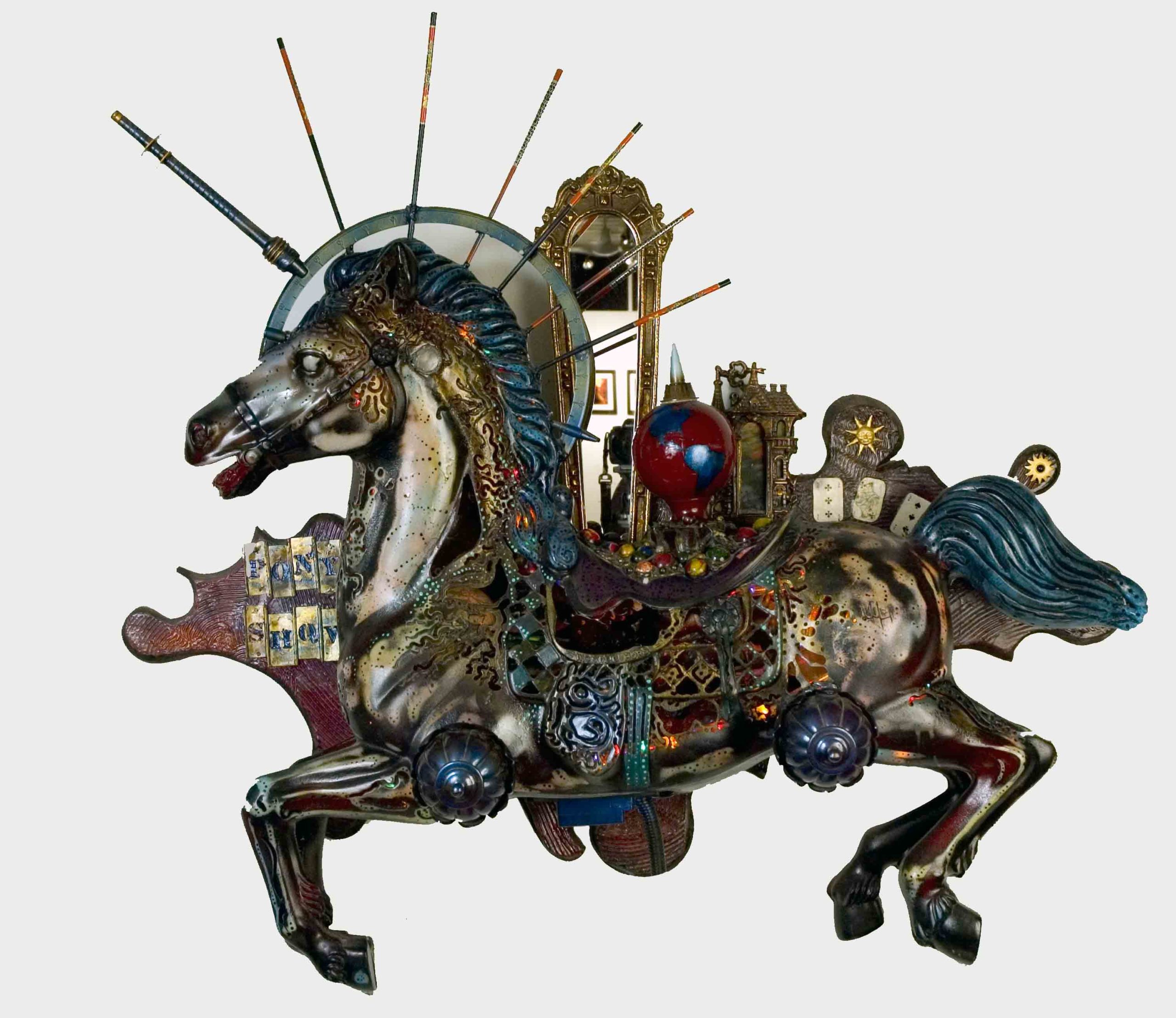

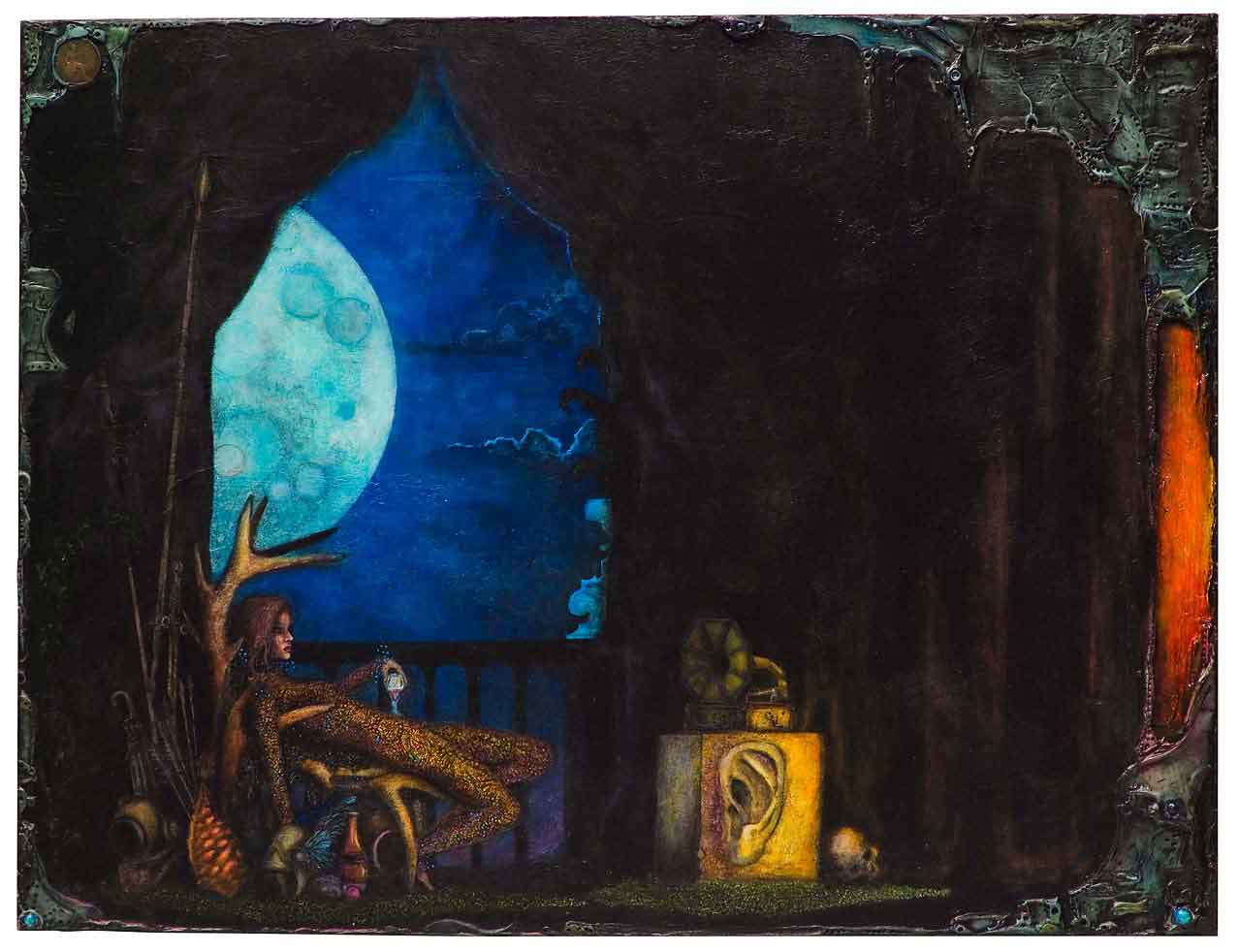

Michael Thomsen was born into a line of circus people and performers, and, in a way, hes continuing in the family business. Thomsens artwork carries unmistakable marks of the carnival: gothic gilt mirrors, lights, lurid pinks, blues, and yellows abound. Carousel horses leap from the wall; fortunetellers and ring toss games compete for your attention.

Thomsen grew up in Austin, Minnesota, in the shadow of the Hormel meatpacking plant, according to his artists statement. His family had been in the circus business for generations: relatives that emigrated from Europe to the U.S. at the turn of the century were members of the Danish Royal Circus; Michaels grandfather established a successful midway business around a circuit of county fairs in California. Thomsen fondly recalls childhood vacations to see his relatives on the west coast: I loved visiting the fairs and getting to see what happened behind the scenes. I think it made a huge impression on me.

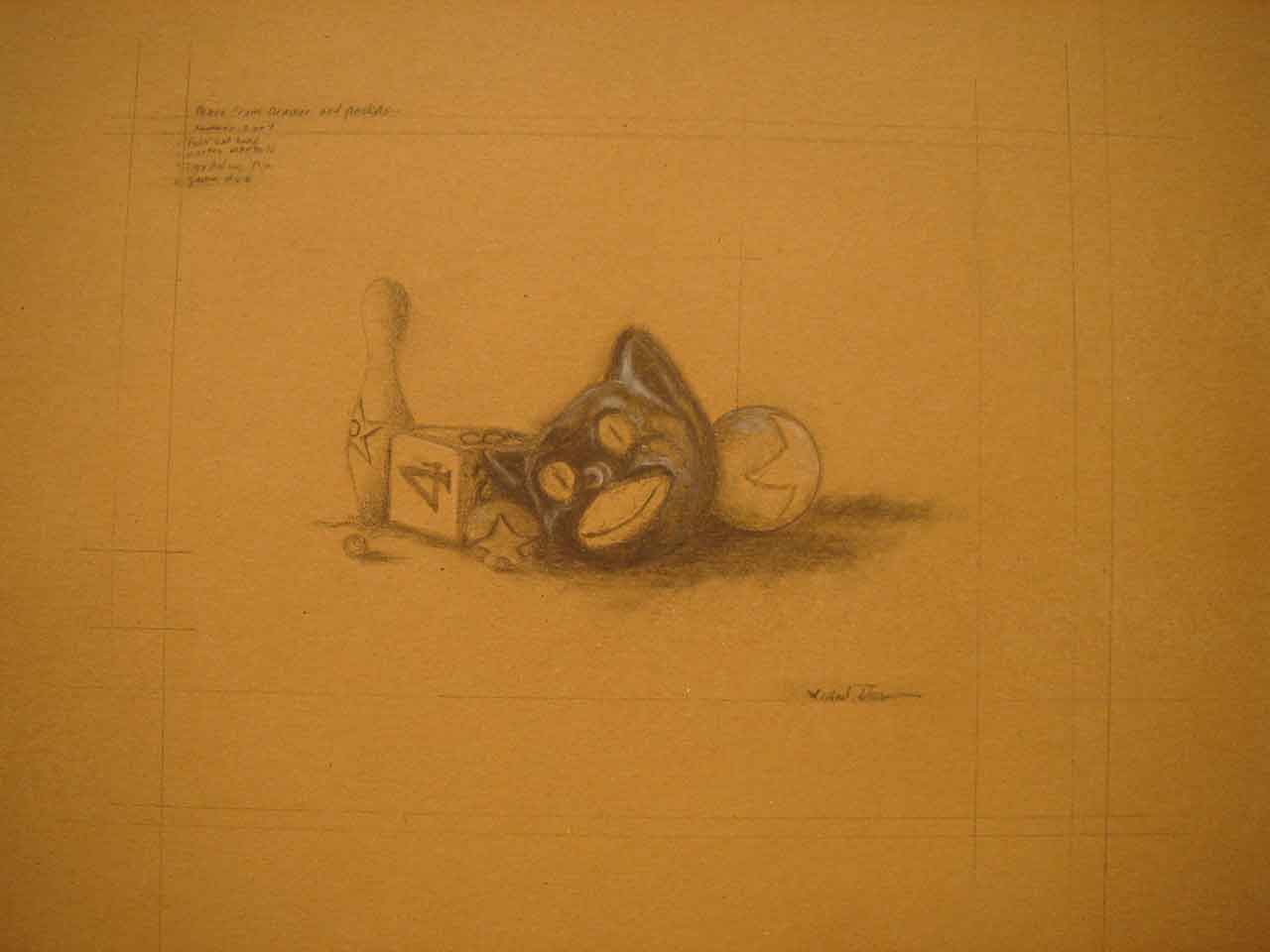

During the off-season, that same grandfather served as an itinerant auctioneer. Thomsen worked for himhis first job as a kidsorting through the junk drawers and closets of the recently deceased, taking an inventory of their belongings for the subsequent estate sales. I loved going through those old drawers, he says. You find the most amazing things in there. It is powerful to touch all those small, personal thingskeys, playing cards, watches, little odds and ends. People spent a lifetime collecting these things and they handled them every dayjust think about how you handle your keys. I sorted through them, and if something caught my eye, I would take it for my own. In fact, some of the things I pocketed back then still show up in my work.

As Thomsen explains it, adopting these small effects allowed him to connect with people, albeit remotely. I had a sort of dyslexia as a kid, so I always felt a little disconnected from other people. I just couldnt understand things the same way everyone else did. I think I lived in my own head most of the time.

For a kid who had trouble fitting in, who was more comfortable with images and objects than words, adopting these private relics of lives past was a powerful means to human intimacy. These were the things people carried on them, right in their pockets; these were things they used and touched every day. These things have life in them. Whats more, Thomsen remarks that, in rescuing these pieces, he felt like he was able to mitigate some of bleak finality of death. I like the idea of providing a little world for these things when their original owners are gone, he says. I still love that aspect of picking something up at a garage sale, or an estate sale, or a thrift store. I feel like by giving these things a home, death doesnt have to end it alltheres some continuity between their lives and mine.

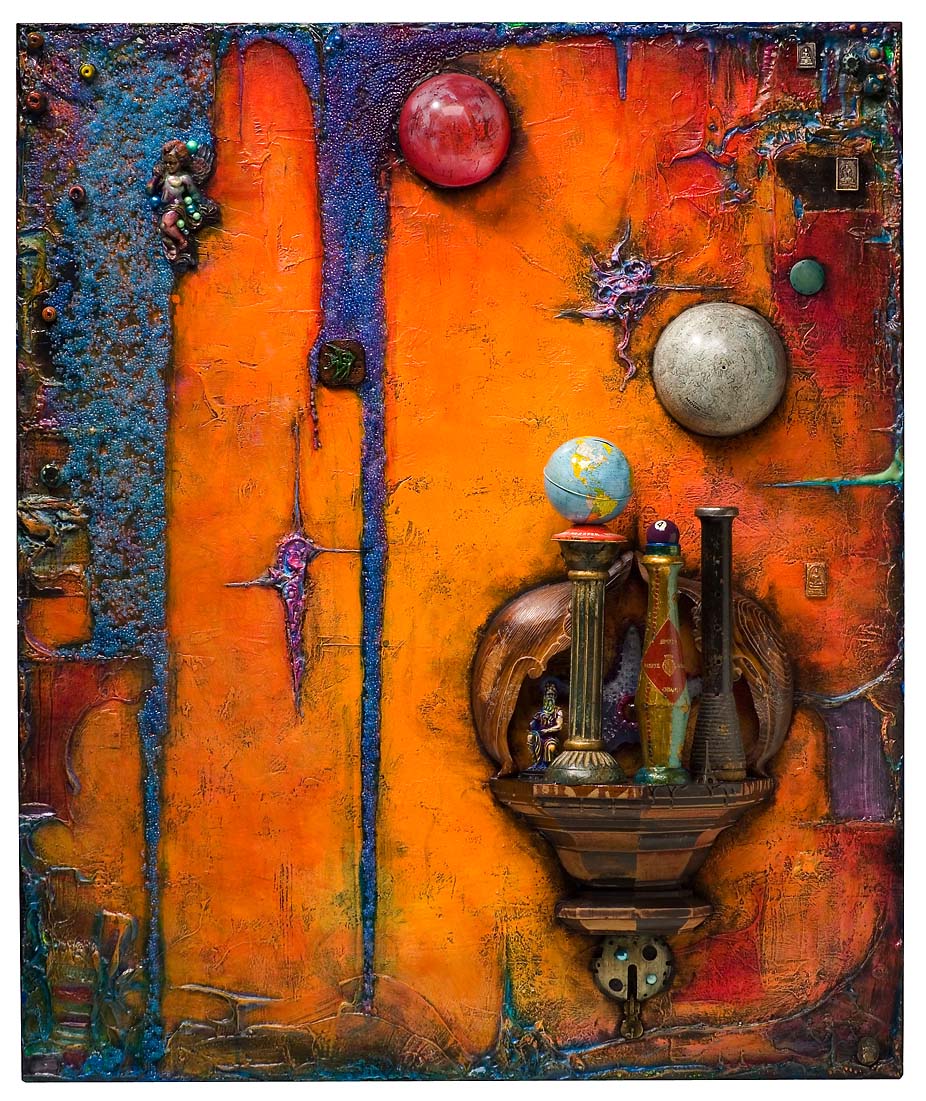

In a way, I think thats the motivation behind the pieces I make, Thomsen explains. I create little worlds where these objects I find can live. And finding the right objects, picking them up from thrift stores or estate sales, is a big part of the process of making the work. Im really careful about which things go wherethey have a relationship to one another. In each piece, these things have to live together, and each part has its own personality to take into account.

Thomsens creationslying somewhere between collage, sculpture, and paintingare intricate marvels of engineering, found objects, paint, and fabricated structures. Each piece is a self-contained microcosm, peopled by objects and laden with symbology whose meaning is dictated by dream logic, rather than the rules of the waking world. Thomsen agrees, Actually, the inspiration for a lot of these pieces comes directly out of my dreams. I usually dont even like to talk about it muchif I describe the individual elements of these pieces and what they mean to me, it feels like Im giving away something too personal. Im trying to create fully realized little worlds.

In Thomsens Wonderlands, you get to be Alice. Get close enough to touch it, spend some time looking under the horns jutting out of the middle, and feel around inside the nooks and crannies behind the carousel horse. Turn a nondescript crank on the side of Clock and the tinny melodies of a hidden music box emerge from within; peer closely into the crystal ball at the center of Roundabout and youll find a tiny painting tucked inside. The imagery of Thomsens work hails straight from the carnival lurking in the recesses of our childhood wishes and fears. Menace lives cheek by jowl with the sublime, harlequins and fortunetellers, cherubs and horned beasties, mirrors and gearsthey all bark for your attention. The imagery and structures of each piece are mind-bogglingly complex, but resonate with an inchoate sense of order all the same.

To me, the little worlds in these pieces have the same balance of light and dark that the outside world has, Thomsen explains. Everythings therethe good and bad, ugly and beautiful. Im just showing you how I see it. It may not be easy for others to figure out the meaningjust like the real world doesnt always make sense to me. In these pieces, I have the ability to arrange things in a way that reflects how I see things, by the rules that make sense to me.

About the artist: Michael Thomsen was born in the shadow of the Hormel meatpacking plant in Austin, Minnesota, to a family that included auctioneers, painters, circus performers, a clock and violinmaker, and a former member of the Lawerence Welk ensemble. With a slightly demented toy makers fondness for odd mechanics and disturbing juxtapositions, he uses found objects scavenged from thrift stores, alleys, rummage sales, and junk drawers to create a multilayered dream reality.

If you visited the November exhibition, Festival of Appropriation, at the Soap Factory you likely saw a number of Thomsen’s pieces on display. His work is currently showing as part of a group exhibition presented at the prestigious Art Basel in Miami Beach, Florida December 6-7. Inquiries about specific pieces may be directed to Flanders Contemporary Art Gallery or Rogue Buddha Gallery.

Susannah Schouweiler is editor of mnartists.org.