Portraits, Practice, Pleasure, and Process

A transatlantic conversation with Ajamu, Leslie Barlow, and Sayge Carroll: on the sensuousness of material and its potential to transform the experience of identity

In conversation: Ajamu, Sayge Carroll, Leslie Barlow Transcribed by Ego Ahaiwe Sowinski

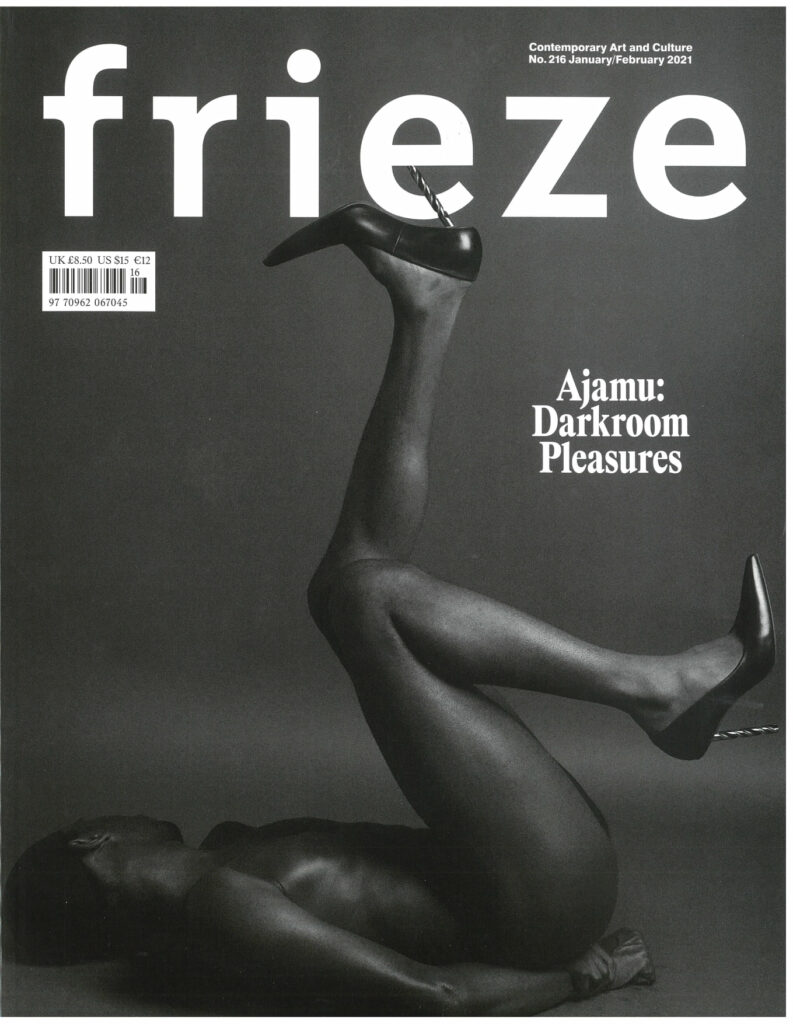

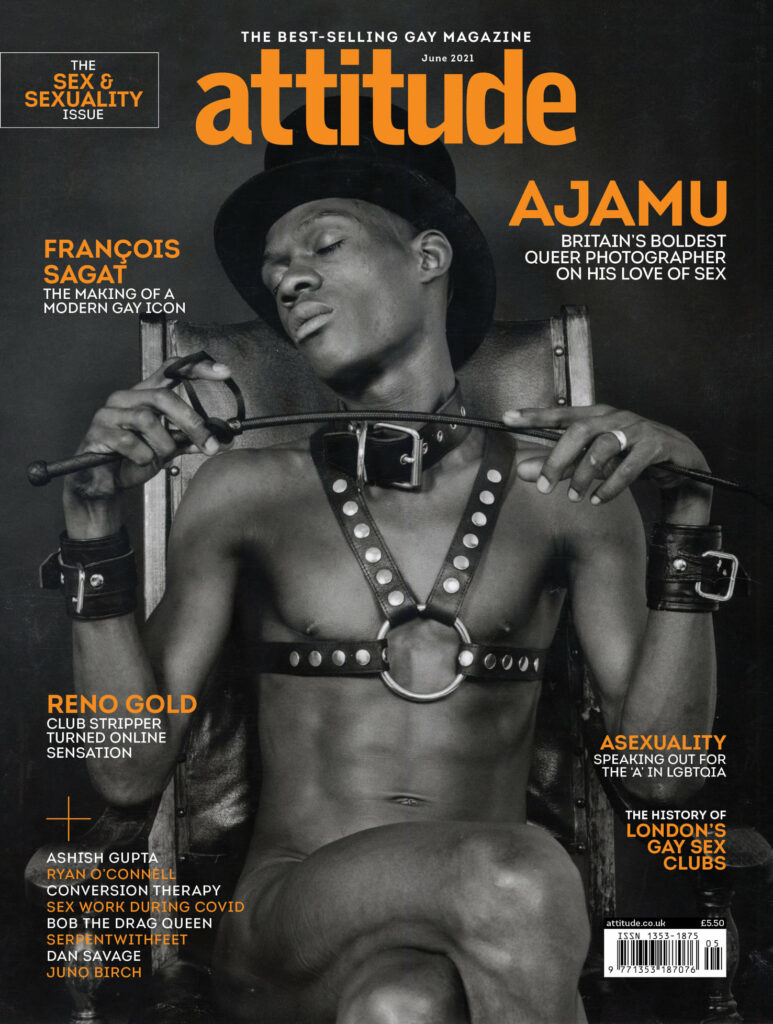

This interview is part of an ongoing transatlantic dialogue with artists and scholars from London and the Twin Cities. Ajamu is a British fine artist-scholar, curator, archivist, and activist who has been at the forefront of genderqueer photography since the early 1990s. His studio, which is also an accessible community space, is based in Brixton, London. Ajamu has been documenting ongoing, key figures in Black British queer life through portraiture. His theoretical provocations, politics, and the aesthetic qualities of his work unapologetically celebrate Black queer bodies, the erotic, sex, pleasure, and play. As an independent archivist, Ajamu has been involved with Black Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans, and Queer communities and wider social justice activism for over 30 years. Consequently, Ajamu has accumulated the largest photographic archive documenting Black LGBTQ+ life in Britain. Ajamu is currently developing an archival heritage project that aims to activate his personal collection and a unique pictorial of LGBTQ+ history in Britain from the late 1980s to present day.

Ajamu is currently one of six contemporary artists responding to the lost erotic drawings of Duncan Grant, the British Modernist who was a member of the Bloomsbury Group, in the exhibition Very Private?, which explores themes of sex, intimacy, gender, and identity. On display are 40 of the 442 drawings from within the Grant collection, which was gifted to Charleston, an old farmhouse in Sussex which was the former home of Grant, who had lived there with Vanessa Bell. The exhibition, which ends March 2023, is the first public exhibition of Duncan Grant’s erotic artworks.

In May 2022, Ajamu met with artists Sayge Carroll and Leslie Barlow at his studio whilst they were visiting London to discuss art practice, pleasure, and process. He also took their portraits.1 The conversation was facilitated by Twin Cities-based friend and collaborator artist and archivist Ego Ahaiwe Sowinski as part of an ongoing strategy to connect networks of artistic practice and create space for dialogue in the UK and the Twin Cities.

AjamuWe are here in Ajamu’s studio in Brixton, London. What is your name? And what do you do?

Sayge CarrollMy name is Sayge Carroll, and I mainly I work in clay, but I am a multimedia artist. Clay is my home, but I use a lot of other things. You want me to expand on that, don’t you?

[Laughter.]

AYes, just expand on why clay is your home.

SCI did photography for about 20 years, and I really loved working in the darkroom. When it went digital, I just wasn’t able to embrace it in the same way. I also had my son and I only wanted to take pictures of him; I didn’t want to take pictures for anybody else. I used clay in high school, but I came back to it because I had a daycare. My Tuesday evenings were for me, and that’s when I did clay. There was something about clay. With photography, the darkroom was where I loved to be. With everybody getting a camera, it just didn’t feel as expansive as I wanted it to be. So, when I started working with clay, it was just something that I understood innately. I was able to make it do whatever I wanted it to do. It was like I went from framing the pictures to creating the world. I can’t go wrong with clay. I also work with sound, so in recent years, I have incorporated making instruments and making large sculptural pieces. [Sayge shows Ajamu a photograph of one of her Sacred Wombs on her phone.] If you can see, I’m building inside the kiln. I’ve made about three pots that are about 53 inches or so by three or four feet wide. So you can climb inside of them! I also make tableware, lamps, and utilitarian things as well. Clay is so versatile. You can just do everything that you want with it, and there is fire involved, and I love that.

ASo my question is, do you think that there’s a correlation between the darkroom and working with clay?

SCYes, I do think there is. When in the darkroom, you get to control what people see. Just the whole process of building the photograph—the focus and where you can make people’s eyes go. For me, it was an easy transition to start doing clay because I was creating exactly what I wanted people to look at. I don’t really know how to articulate the transfer and why it felt so good, but it did feel like before I was documenting the world, and now it’s like I’m making the world. It felt like I had so much more control over everything once I started using clay. With photography, it started with me just taking photographs. Then I started to make the environments, and then set up those environments—not so much like it was a still life, but rather whole rooms and environments. Now with the clay, I get to play. I’m making the environment, I’m adding sound, I’m adding texture. I am adding all of those things as well. But my work is something that you need to experience. I guess it’s an interaction between the viewer and the pieces that I make. When I’m working with clay, it’s a collaboration with me and with the clay. You have to pay attention to what clay can do and what clay wants to do. You can’t just impose your will. So it’s just kind of wonderful.

[Interruption: Sayge’s phone is buzzing: it’s Ego calling from Minneapolis to check in.]

AI have a question around clay and the darkroom again. What is the role of sensuousness in your process? This is my main question.

SCOh! Clay is…is… [Deep sigh and exhale.] Clay is completely a sensuous process. It is all about feel and texture and smoothness. You can play with it in so many different ways. There are certain things that I don’t teach at high school. For example, I don’t teach pulling handles, just because it’s way too, you know, suggestive of other actions.

AGo on. This is what I want to hear.

SCOkay, so it is way too suggestive of, you know, stroking or getting someone off. In one of the classes that I teach, everybody is watching The Great Pottery Throw Down. It’s like The Great British Baking show, but with clay. So the students were discussing a thing on the show about pulling the clay, and the sensuality. I always remain professional, but it’s hard to do just because of how sensual it ends up being.

AYes. That’s my question mainly around process, because we don’t always talk about sensuousness that comes with our process and the sexual. For me, there is a link with the darkroom: it is very much sensuous to me, because you touch and you smell, and the materials also touch you, so I am sure with clay it’s similar again, the touch and smell. That’s the part I am interested in.

SCYes, because when you are first learning to throw, you must keep it really wet. You must make sure that it’s able to glide and that there’s no tackiness to your hands. So, you know, I’m always talking about how wet it needs to be, and how you have to think about if you’re creating heat and think about whether it’s going too fast; if you don’t have enough water in there, it doesn’t glide, and all these things are just innuendos, left and right. I mean, I think that’s probably why I love it so much. This fall I’m going to be working on a performance piece where I get to just have a full-body experience on stage with a bunch of clay with Ego [Ahaiwe Sowinski]. My main concern is that it’s not going to be like mud wrestling for us. There’s gonna be some play like that, I’m sure, but you know. I want to be able to completely experiment and immerse ourselves in it. It is a two-day durational piece, so we get to kind of see how that plays out, along with the soundscape using the instruments that I make from clay.

AWhat is it about the going back into this large piece? Is there something about going back into the dark? I have an idea that maybe it could be a darkroom that you go back into through clay.

SCWell, the large pieces that I’ve made are wombs. One was about the loss of my first born. You would assume that your womb’s the safest place for your baby before birth, you know? For him to have died in my womb was devastating and infuriating. And so, yeah, I’ve done a lot of womb pieces. There’s something about being inside that cavernous kind of space. It’s cool, it has a certain sound to it, and it has a certain kind of feel to it. So, I kind of want to do this with wet clay. That’s the next step. I think it is just about getting inside of it, getting around it, feeling it, and impressing my feet on it. Kind of all of that!

AWhere does time come into it?

SCOh! Okay, so there will be two pieces that will be flanked on either side of the stage—it will be theater in the round.2 I am making two larger pieces that will be greenware, and greenware is clay before it’s been fired. One will be sitting in water, slowly disintegrating down—and may topple, who knows? Depending on how it disintegrates and how it takes the water in. And the other will have water dripping on it so it will slowly disintegrate away. The vessels are present as a tool for marking time. It will be a pretty slow process, but it’s really significant that just a drop of water can bring this whole thing down. It’s going to be more of an exploration of sense and feeling. Ego was the first person I did a performance piece3 with before, and I was talking with my friend, Pramila Vasudevan,4 who’s helping me to navigate performing because I don’t do that a lot. And I was talking about the playful side of it, that I want to get in there, and she suggested I probably should have somebody with me to do that. And Ego was like, “Yes, I totally want to do that.” I’m really excited about it. We are collaborating with artist and writer Keegan Xavi.

ASo, can you tell me your name and what you do?

Leslie BarlowMy name is Leslie Barlow. I do a lot of things; I wear a lot of hats. My art practice is mostly painting, but I also have a social practice as well. I am an educator and a Studio Program Director for emerging artists.5

ASo, in painting, what kind of ideas do work with?

LBIdeas? I mostly work in portraiture. I am exploring topics of race, identity, and relationships—how we come to know ourselves and how we come to know others, how we’re in relationship with one another. Along with that, I am also really interested in what painting can do, as far as an archive, as far as a place to visually represent ourselves, but also a place to hold power. The people that I represent or share stories of, or share representations of, are people that maybe historically haven’t gotten to take up a lot of space in painting.

AWhat kind of materials do you paint with?

LBI am an oil painter—that’s kind of the basis which you might recognize first, but then I also collage a bunch of different things together in my painting, so there’s textiles sometimes, quilting. Photography is a part of the work, not just the photos I take of people, but sometimes I will weave in photo transfer, collage it in, and I use drawing materials, pastels, and things like that.

ASo then, what does oil do for your work and materials like pastels? Or the idea itself?

LBWhat does it do for the work? I guess I love oil, you know? Sayge, I love how you were talking about clay, because oil to me is also very—the material—well, its history, right? People have been painting for a long time. And I just like thinking of pigments, and the dirt and everything that the paint is made of.

ACarry on, carry on, you’ve mentioned my favorite word there—”dirt.”

LBI manipulate it. It comes in these tubes, it’s this material, but when you look at my painting, I’ve completely transformed it into something different, right? And I really like that. I like that everything from my imagination gets put through this raw material, and becomes this super layered illustration of all these beautiful things. I feel very connected to people through time with painting, because people have been doing this with color, with pigments, for thousands and thousands of years. Right? I love that. As someone that was brought up in Western education, and thinking about Western art, seeing portraits of saints and royalty and people with money, a lot of white people, being able to paint people in my neighborhood, my family members, people in the community—because I mostly paint Black and Brown folks—that, for me, feels very empowering. It feels like a twisting of those narratives that were ingrained in me as a child.

ASo then, the same question, the role of sensuousness in the work, in process? Because I was really excited by the word “dirt.”

LBYeah!

[All laugh.]

SCThe raw material!

LBThe raw material!

[All laugh.]

ABasically, I am curious about the process. You’ve talked about process in terms of ideas, but I am interested in the process itself—not always about the ideas in process, but just the physicality.

collectivelyThe physicality!

AYes, the physicality. What is that doing in terms of the work or the ideas? It’s that thing. I’m just curious about the process.

SCIt’s a different way of thinking about it.

LBYeah, I’m going to try to answer. I don’t know how but I’m gonna try to get there. I love it. I don’t often get asked about that, you know, as a painter. It’s always about the concept, people asking you about your concept or the ideas. I don’t often get asked about the materiality of paint.

AExactly. I have a view on that that I might share later.

LBSame. I love talking about the materiality of paint because that’s why I chose it. I love its slipperiness.

ATell me more.

[Laughter.]

LBI love how I can play with the weight of it, when I am manipulating it on a surface, and I like really rigid surfaces so I can push the paint into it. Whereas canvas, the texture for me isn’t always as exciting.

AWhat does that pushing do?

LBThe rigidity of the wood panel?

AYes, what does it do? I have a thought here, but I am asking you, what does it do?

LBWell, it pushes back. There’s a relationship I have with it. There’s a fight that kind of happens. Sometimes it’s a dance, it’s not always a fight, but there’s definitely a push and pull. With the paint, there’s a lot of backwards and forward motions, and what’s beautiful about oil paint is it doesn’t dry right away. I can layer it very thin or thick, right? So that’s what I was talking about, the weight of it. I like to work in a lot of thin layers, and then I’ll get to the thickness of it. But with the thin layers with oil paint, you can take rags, your fingers, different things, you can wipe it away and reapply and there’s just a dance that happens with the material, you know what I am saying? And I don’t ever have a premeditated idea, I’m not going in knowing exactly all the moves that are gonna be made. So it’s very visceral and it’s very embodied.

ARight, fantastic. Last Friday, myself and Sheena Calvert did a talk around Ingrid Pollard’s6 work at the conference and we spoke about the Sensuousness of Process.7 So, my argument is that lots of Black and Brown queer work is only read through the lens of its content, i.e., representation, i.e., identity.

collectivelyYES! YES! YES!

ASo actually, what is missing from a lot of conversations about Black and Brown artists is process and making.

LBYes. Absolutely. Absolutely.

SCYes. I love that.

ASo, what is then missing—it’s very interesting that we don’t get to talk about what is not done to Black bodies, and then what does the process do to our own Black and Brown bodies?

LBWell, it’s rest, its healing, it’s everything. You lose time. I’m so aware of my body in space outside of the studio. But when I’m painting, I’m fully present. I’m losing time, it’s very natural. I feel very connected to the work.

AYes. That’s what I wanted to try and get to. It’s that our bodies are central to the process.

LBI love that. Yes, absolutely.

SCOh, completely.

AYes, it’s embodied, yes, it’s sensuous, it’s pleasurable, all that kind of stuff, that we don’t always talk about as creatives. It’s often just about discussing the thought behind it or the concept.

LBWe were talking about this the other day. In grad school, they told us that if we didn’t have a thought or concept, it wasn’t even meaningful.

SCYes, exactly. The whole thing for me with clay is I could lose myself or lose time in the darkroom. And when I had to stop using photography in that way and stop losing time that way—on a computer, I couldn’t do it. Clay is very tactile. It’s like having my hands busy. And knowing there’s this set of variables that I’m working with, I can stop thinking about it and I can just be doing it or living it. With clay, it’s even more control, it’s more embodied, and half the time when I start making things, I don’t even have an idea of what I’m going to make. It’s more like, “What is going to happen today?” And you are kind of told as you go—by the clay—and it’s the best way to spend my time. It is the most healing. It enables me to get up and go back outside and deal with the screwed-up world.

LBYeah, ditto.

ASo, going back to representation and identity—I’m thinking aloud here now—do you think that in the moment that you’re in your process, do you think it’s possible that what gets lost is your identity?

SCWell, you don’t have to think about it.

LBI had a conversation with what I call my participants—not subjects, the people that I work with, making these paintings—a similar conversation that’s in alignment with this, about the pandemic. I asked them, as I was taking their photographs, if they had thought about their identity recently. Have you thought about it lately? Since you haven’t left your house, and you aren’t in the gaze and everything else that you normally navigate outside your home space, your safe space. Most responded, after pausing to think, “No! I’m just me, right?” I’m not having to navigate these other kinds of constructs or things like that. I would say similarly, when I’m painting—I mean, it’s spiritual, there’s something else there. I’m not necessarily thinking. When I say that I’m thinking about identity and being intentional about the people that I choose to paint, I’m not checking boxes. People don’t have to look a certain way or be a certain way. It’s more about—I love this community. I love these people and there’s a sense of kinship and belonging I feel, and that’s really what leads me to making those paintings, you know. And so, for me, when I’m in the studio and I’m having the connection with the work, it is not so much all the heavy identity with a capital “I.”

AI like that you spoke about oil, let’s go back to oil. Again, I’m thinking aloud—could oil be a metaphor for how you work with identity?

LBSure. Yes.

AOkay, could clay also be a metaphor for how you work with those ideas? It is malleable; it does all kinds of shapeshifting.

SCI think it could be a direct metaphor for my life. With clay, you can make it fit whatever you need it to fit. Growing up with my mom and her white side, or my dad’s Black side of the family, and me always having to shapeshift, trying to fit into whatever their expectations of me were. I think that as a metaphor it works. However, when I am working with clay, nobody can tell me I’m doing it wrong. Whereas when I’m walking through the world, I hear that I’m doing it wrong a lot.

LBThere is literally much more power. I was going to say that when you’re the maker, when you’re the artist, you have much more control. The material also has its own voice, but you have much more control than outside of the making space.

SCMy thesis was literally making worlds, it was making other worlds and just kind of filling them out with what I wanted, what I needed. That’s actually why I started making. We were poor, and there were things I wanted, so I learned to make some of those things. I got better at making them than things that were offered that I could buy, and I preferred the process. The process gave me time where I didn’t have to be concerned about my identity, I didn’t have to be concerned about any of those other things. I could just be.