Zen and the Art of Moviemaking

David O. Russells "existential comedy" is thoughtfulbut is it funny?

I [Heart] Huckabees

Directed by David O. Russell

20th Century Fox

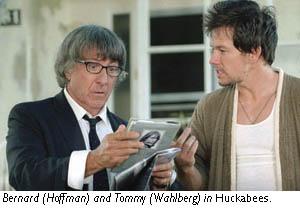

David O. Russell’s film I [Heart] Huckabees was billed as an “existential comedy” when it came out last year, and it received more than a few whacks from critics—seemingly because it dared to be such a thing. Roger Ebert dubbed it “inexplicable,” Slate’s David Edelstein thought it “fatally over-intellectualized;” others voiced their exasperation in even less polite terms. An ensemble piece, the plot follows an environmentalist, Albert (Jason Schwartzman), and a fireman, Tommy (Mark Wahlberg), who get bounced like ping-pong balls between the dueling ideologies of the nihilistic Caterine (Isabelle Huppert), and the open-hearted Bernard and Vivian (Dustin Hoffman and Lily Tomlin), who espouse the virtues of interconnectedness. Both philosophies have their charms, the film argues, but Caterine’s gets most of the laugh lines. “Once you realize the universe sucks, you’ve got nothing to lose,” Tommy proclaims, as he and Albert whack themselves in the face with rubber balls in an effort to get in touch with the futility of it all.

Without question, the film is overstuffed, a victim of its own brainy enthusiasm. In the same way some bright teenagers get when they first discover Sartre or a movie with subtitles or good pop music that doesn’t get played on the radio, Russell is eager to entrance you with his shiny new philosophizing. After a while you feel exasperated hearing about his big ideas even if you agree; even so, the film’s a sputtering mess that you can’t help but sympathize with. Actually, it’s impressive that the film hangs together at all in its attempts to take on so much. Brad (Jude Law) and Dawn (Naomi Watts), husband and wife, are suffering from existential crises of their own, which Russell seems to trace back to their employment for Huckabees—a Wal-Mart-like chain-store behemoth. The director takes a few shots at the both the oppressive enormity of the company and the expectation of unthinking loyalty demanded of Huckabees’s employees: in a telling scene, the higher-ups are aghast when Dawn dares to replace the “H” in the company’s name with an “F,” horrified that any member of the team would speak ill of their employer.

This line seems more an easy joke than insight, though, and it’s hard to pin down exactly what Russell wants Huckabees to stand for. Here’s where an enlightening DVD commentary track would come in handy. Unfortunately, even with the director’s remarks, it’s hard to pin down Russell’s specific intentions. His general bitterness toward corporations—particularly what he sees as their disingenuous “green politics”—comes through clearly. And smattered among his standard-issue chatter about how fantastic so-and-so was to work with are more than a few political riffs—he comments on the charms of Adlai Stevenson, and argues that America’s failure to enact Jimmy Carter’s energy policies led to the “existential dagger” (his words) of 9/11. While it may be interesting to hear his views on such things, what exactly this has to do with the making of Huckabees isn’t entirely clear. In fact, the comments sometimes seem better suited to his previous movie, 1999’s Three Kings, a brilliant tragicomic take on the end of the first Gulf War.

Russell’s on much firmer ground when he talks about spirituality and emotions, particularly when it comes to using them to guide his actors. He reveals that one of Wahlberg’s favorite actors is John Garfield, and, sure enough, Russell’s gone to pains to cultivate a square-shouldered and impassioned acting job out of him. A longtime attendee of a Manhattan zendo, Russell clearly spent time thinking about where his characters’ neuroses stem from: middle-class upbringings, the egoism he finds in most religions, the “tyranny of your habitual mind,” an so on. With Huckabees, he explains early on, he wanted to attack those concerns by coming up with characters who reflect his favorite kind of people: those “who follow an idea or cause beyond convention.”

As guideposts towards a personal philosophy, such thinking is admirable. As fodder for comedy, it’s all but deadly. Thankfully, Tomlin and Hoffman find ways to bring a screwball element to their investigations, and their interjections are richly comic: they barge into other characters’ brains the way thugs with guns burst into bedrooms in ’30s noirs. But some of the actors, Law in particular, appear to be at sea about how intensely they should be reacting to all of this epistemological guff. Watts, who seems perpetually thrust into roles where she’s forced to transform from pretty to ugly, does much the same thing here—shifting from perky Huckabees sales gal to a despairing “Amish bag lady.” Forget Russell’s business about going beyond convention—she just stuck with what she knows. Anybody who’s willing to meet the madcap philosophizing in I [Heart] Huckabees halfway will find something to love in the film. But any movie about—and made by—people stuck in their own heads is going to be more fun to think about than to actually watch.

To read more DVD reviews, visit Ruminator’s web site www.ruminator.com