Yes, We Do Have a History: “In Her Own Right” at MMAA

Susan Clayton reviews "In Her Own Right: Minnesota's First Generation of Women Artists" at the Minnesota Museum of American Art

In Her Own Right: Minnesota’s First Generation of Women Artists is a pleasing collaboration between the Minnesota Historical Society (MHS) – drawing on its fine art collection and exhibition know-how – and the Minnesota Museum of American Art (MMAA), possessor of an expansive gallery space that is used for temporary exhibitions.

At present, neither institution is quite whole: MHS is our official trove of Minnesota art objects and knowledge, but lacks a dedicated gallery – aside from James J. Hill’s beautiful but antique salon, tucked away in his mansion on Summit Avenue. The MMAA, with an extensive collection of its own, has no permanent place to install it and, therefore, no visible way of communicating its long history of service to the arts community in our state. It seems natural that these two bodies work together. We can hope this exhibition begins a long collaboration.

Promised was a show of 75 works from five artists, Frances Cranmer Greenman, Alice Hugy, Clara Mairs, Josephine Lutz Rollins and Ada Wolfe. All were born before 1900, enjoyed lengthy careers, and “contributed greatly to the history of art making in Minnesota.” True? Well, yes. In order, these women were a busy portrait artist and writer, a successful commercial artist and activist, a prolific painter and printmaker (and one of Minnesota’s early “bohemians,”) a University of Minnesota professor of painting, and a longtime public school art teacher. These women have their era in common as well as biographies that help tell the story of the twentieth-century rise of American women in the professions.

MHS Curator of Art Brian Szott, who organized the show, is not rewriting the canon here. It is well documented that women have been artists and arts administrators since there were Minnesota walls on which to hang pictures. Art was an approved pastime for women with means and, importantly, an acceptable career choice.

What Szott does do is bring together a good mix of work by each artist, combining the images with solid research presented well. Visitors are given an idea of each woman’s career life, with added bits about the impact of domestic situations, and some useful critique of style and technique. A not entirely out-of-place pair of panels on the American suffrage movement introduces the show.

This is a painting exhibition – with the exception of a group of etchings from Mairs – and is installed with some drama. Ada Wolfe, the artist we know least about, begins the tour. Her quiet outdoor scenes progress along three walls that enclose an inviting seating area stocked with browsing materials on women’s art history. All of the women in the show spent significant time in the East or in Paris, working with important teachers such as Robert Henri and Hans Hoffman. Before she became a teacher herself, Ada was a student of William Merritt Chase. Her preference for landscape and her loose, sketchy brushstroke show this influence.

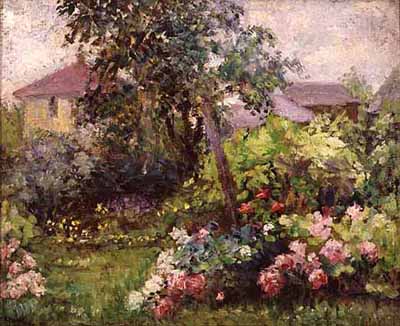

Adjacent to Wolfe is Alice Hugy, her closest sister stylistically. Hugy was a student and teacher at past incarnations of the MMAA. Although pen & ink ad art paid the bills for this artist, the exhibition showcases her painting, gardenscapes and floral close-ups, evidence of her passion for the outdoors. An early proponent of green space preservation, Hugy successfully led a fight to save St. Paul’s Cherokee Park.

Deeper into the galleries are Clara Mairs’ clear-eyed relationship studies – children at play, a lover approaching, a deathbed watch. Mairs’ depictions are still fresh, rendered with humor and charm, yet unsentimental regarding human behavior. Her figures tend to gather in the foreground, her compositions allude to the emphasis on pattern practiced during early work in decorative arts. By all accounts, Mairs was a truly free spirit, often traveling and, at home, painting animals on the walls.

There is a temptation, when approaching the last gallery, to go directly to the far wall, where Frances Greenman’s stunning canvases glow. But Jo Lutz Rollins’ work also deserves attention. Rollins, a wife, mother, professor, and painter, established the Stillwater Art Colony in the 1930s, and in the 1960s organized the West Lake Gallery, a cooperative comprised of women artists. Perhaps it is no surprise that her work seems rushed. Early messy, harsh landscapes in oil do mellow into softer work in watercolor, but it is a trio of whimsical portraits that stand out.

Greenman, however, is the portrait virtuoso. Based in Minneapolis but working also on both coasts, her celebrity clients included Mary Pickford and Lynne Fontanne. The actresses are not here, but Minnesota Gov. Karl Rolvaag and Minneapolis newspaper columnist Barbara Flanagan, given star treatment by Greenman, are. From full-length life-size images to small jewels, Greenman’s work is lush and expert.

Some of the 75 pieces – drawn from a variety of local collections – could probably have been edited out, but that’s nitpicking: what fun it must have been to have so much square footage to play in!

Why should the gallery-going public care about this show? The artists are not a handful of curiosities; many other artists–Wanda Gag, Elsa Jemne and more – could easily have been included. The artist’s stories are not ones of terrible adversity. Although they needed to actively and continually buck convention to do it, they simply did what artists are compelled to do. The women either knew or at least knew of each other (Greenman painted Mairs, Mairs painted Hugy) but they worked differently and independently. To the young artist, or the floundering one, these elders seem to say, “be true to yourself.”

The works themselves give us a record of places and persons from our history. They give evidence of the ways that national and international artistic trends played out locally. Many are wonderful paintings outside of their context (Mairs’ fascinating FaFa and Her Birds, Greenman’s loving study of her husband, John Greenman Reading.) But it’s the artists’ stories that are particularly chewy, and stories are what history and art offer us so well. Portrait painter Greenman knew it: “They say art is eternal. What’s so eternal about art as it is today? Styles are changing faster in art than in hats – I believe the highest thing a man knows – the thing he likes the best and always will – is himself. People!”