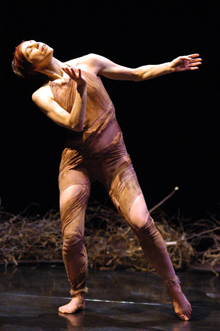

Wynn Fricke: Fierce and Honest Devotion

The choreographer and dancer Wynn Fricke has worked with both the Minnesota Dance Theater and Zenon Dance Company this fall. Lightsey Darst looks at these perfornances in tthe context of Frick's past work.

Upturned Jewel

in Minnesota Dance Theatre’s “Putting on the Ritz”

at the Ritz Theater

November 3-11, 2006

and Garden

in Zenon Dance Company’s 24th Fall Season

at the Southern Theater

November 16-26, 2006

Writing this is like flinging horseshoes at a stake in the dark. I know Wynn Fricke’s out there somewhere, moving on the strong legs of her bodily talent, carrying the tiny galaxy of her concerns folded up like origami on her back—but I don’t quite know where.

Let’s start with that bodily talent. 2005’s Upturned Jewel, revived at Minnesota Dance Theatre’s recent fall concert, is a wild breathless whirl of a dance, full of Fricke’s fast precision, her fascination with group shape and sequence, and her musical, physical invention. You get hunched figures pawing the ground with splayed fingers, a single dancer twitching and jumping across the stage, a mass of dancers swaying like a sea anemone; you get movement in trickling canon and fast-breathing, piston-action unison; you get intricate knots of bodies and then flickering, flying leaps. Watching Upturned Jewel, you know you’re seeing the work of a choreographer who knows the body’s million inflections, hears her music closely, and pushes the boundaries of timing and detail. (Watching MDT’s fall concert, I must add, you know you’re seeing something extraordinary: the fierce energy of MDT’s dancers, most still in or barely out of their teens, simultaneously harnessed and explosive. I can’t wait to see them again.)

But back to Fricke: beyond her bodily expertise, her individuality’s unmistakable yet hard to pinpoint. What is it that Fricke’s work does? Luckily, Zenon Dance Company’s fall concert features Fricke’s new piece Garden alongside work by Seán Curran, Johannes Wieland, and Cathy Young. The contrast at least helps define what Fricke doesn’t do.

Fricke doesn’t do senseless virtuosity à la Curran’s Coda. Virtuosity, yes: take a gasp-worthy lift-leap involving three people that comes jutting up at the audience like sudden architecture. Fricke’s relentless, working her dancers as if they were machines, but the relentlessness always feels in the service of something—think of dervishes whirling towards transcendence. She’s not interested in meaningless visual fireworks.

Fricke doesn’t, like Wieland, work in the meta-realm. Wieland’s spellbinding corrosion toys with the idea of whether the dancers are meant to be men and women. Of course they’re not meant to be men and women, they’re merely visual shapes, but then Wieland puts the female dancers in dresses and the men in pants and shirts and even poses them in a long fake-kiss, so that as you watch this finely detailed, ever-shifting shape-collection, you’re forced into confrontation with your own stupidly insistent meaning-making apparatus. . . Well, however delightful the tangle, Fricke would never do that to her audience. She’s sincere. She aims at union rather than self-consciousness.

Where Cathy Young wears her reading material on her sleeve in the content-heavy Magician’s Wife, Fricke’s not remotely topical. Even when she creates a dance about Frida Kahlo (The Two Fridas, last seen in 2005) or about soldiering (Lament, premiered in 2005), she stays in the marrow of her material. The flicker of detail—Magritte-inspired screens used to create old-fashioned magician effects—feeds Young’s imagination, but it’s not for Fricke.

The Magician’s Wife trails off into an anticlimactic quiet; it’s missing a third act. This never happens with Fricke’s work, and here I think we’re getting to the heart of her difference. Fricke’s work rarely seems finished—it just ends someplace—but it’s not anticlimactic, because Fricke doesn’t work with dramatic arcs. Garden has a sort of story: one angsty figure (Mary Ann Bradley) opens the piece, writhing alone in a maze of others; by the end she’s been gathered into the fold and is climbing, with plenty of assistance, the back wall of the Southern Theater. Fricke works at composition here, carefully building her steps, but the plot, such as it is, feels pasted on. Drama, as we usually understand it, isn’t her strength.

But drama as we usually understand it is a pretty artificial construct, with its epiphany in every pot. Back to Upturned Jewel: this pawing, prancing dance, backed by Toby Twining a capella oddness, evokes images of animals and early humans. The drama here is the continual discovery of the world: the discovery of fire, of one’s own body, of unison movement, of night and day. Fricke’s Lament gets to the heart of the idea of war; her Call and other works explore the origin of religion. Fricke doesn’t move with the times towards irony and self-consciousness; her sincere exploration of the communal and anonymous life of the body is far from cool. And this is probably why it’s hard to talk about her work: her best pieces (and neither the compromised Garden nor the happy Upturned Jewel are Fricke at her best) take us where we’re not used to going.

Fricke’s demanding dances strike me as a religious believer’s steps towards bliss and transformation. As far as I can tell, she hasn’t gotten there yet—thus the lack of endings in her work. But we can’t have everything. It’s rare even to get this close to such fierce and honest devotion.