Words and Pictures at MCAD: McKnight Fellows

Chris Atkins visits the exhibition showcasing this year's McKnight Fellows in Visual Arts at the MCAD galleries. There's some intriguing thematic unities at play; go check it out. The show is up through August 12.

What is exceptional about this year’s MCAD/McKnight Fellows exhibition, compared to recent years, is the shared formal and thematic current running through all of the works. Whether all of the artists came to the fellowship with projects that explore commingled images and text, or whether they arrived at the same point clairvoyantly, I don’t know– but the Fellows have succeeded in bringing some new possibilities to text/art combinations..

Suckers. We all know there’s one born every minute. Chris Walla asks: do they die at the same rate? His Sucker, one of the stronger works in the show, has pride of place as you walk into the MCAD galleries through the main entrance. Each letter of the word is a 5-foot-tall block that has been faced with hand-wrapped paper flowers. Some may see it as an art-world indictment or a finger pointed at unsuspecting visitors. It’s actually closer in form and function to something we’d see at a funeral. The flower-foam-green letters, riddled with cheap paper carnations and propped on easels, are curious equivalents of the coffin-flanking lace-beribboned sympathy wreaths that usually read simply DAD, MOM, BROTHER. This one is actually quite funny, and it’s funny because it’s camp: camp lays the benediction of humor onto serious critical detachment, and it could apply to an implied funeral for art or to something closer to home..

Sucker also asks us an interesting question: do, or can, words ever die? We know the strategy of repeating and reappropriating slurs in order to dull their power to insult and demean. But that doesn’t mean the words go away completely, or that people will stop trying to bring them back.

While Jan Estep’s contributions to this year’s MCAD/McKnight show is diverse and multifarious, the most elaborate of her projects is a large-scale conceptual map she began a few years ago. Trail Map to Wittgenstein’s Hut is just that, a take-away trail guide that charts Estep’s trip to the woods of western Norway in search of the Austrian philosopher’s retreat.

Part pilgrimage and part performative record, Estep’s map is a personal cartography that provides you with directions to a specific location. Yet Estep’s project and accompanying essay are not a heroic adventurer’s log about arriving at the specific location in the wilderness. Instead of pointing you towards a presence, the map leads you to an absence. A grid of photos that accompany the map show how the hut is slowly disappearing into the landscape, overrun with fecund moss and saplings. Going back at the map you begin to realize that finding is less important than looking; meaning and closure, thankfully, are not your rewards.

The hut isn’t a protected landmark and as time goes by, it will slowly become lost in the natural surroundings—then it will disappear. Before it slips from view and from memory, Estep has captured how nicely both nature and building are discernible but inseparable. Keeping this idea of inseparability close by without stretching it too far, Estep has woven, but cleverly not illustrated, Wittgenstein’s texts into the project in such a way that the two, philosophy and art, are intertwined.

Hanging oil paintings on canvas with gilded frames alongside selections of her original poetry, Gladys Beltran has a passionate yet uncritical attachment to American History. By history I don’t mean to say that her work is a succession of specific events or personalities. She’s more concerned with the how of remembering. Beltran’s paintings are fisheye lens landscapes of Washington, DC, that show how America represents its national narratives by ensconcing them in monument-containers that are constructed with a clarity of order at edifying scales. From Washington with Love 6, Beltran’s poem to Columbus Circle goes:

The Sailor [Columbus] will not die/

The Sailor will live forever/

Forever in our memories/

Forever an inspiration.

The work is technically able and she has obviously taken her fellowship year to do some traveling, but it has to be said: I cannot imagine that Beltran has traveled any critical distance from her own work.She seems not to have asked herself any questions about American history or how it is written into the District of Columbia. At the very least, more attention paid to the present instead of the mythic past could enable critical questions that would enrich her art practice.

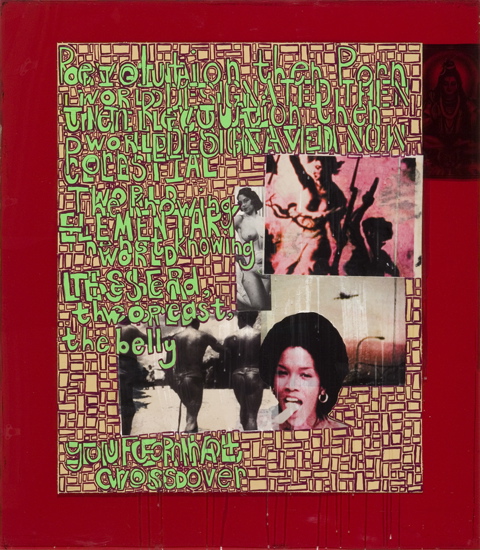

David Bartley’s work is a crowd of photos and hand-painted text. By crowded, I mean that there are many voices speaking at once, not that those voices are too many. His suite of works along the back wall of the gallery aren’t so much as series as they are an essay on this combinatorial practice.

On the one hand, the photos that he has cut from newspapers, art reproductions and popular magazines all speak in their respective visual languages. The images, collected, collaged, and pasted with wax, still carry some contextual baggage from their original sources but are more like visual phonemes for creating specific commentary rather than general discussions of media over-saturation. His text is also crowded, but what’s different is that the words (imagine day-glo graffitoed marginalia) aren’t so much read as heard. Like the overlapping voices of a crowd, Bartley’s words twist and turn in front of and within each other. Imagine not being able to listen to the voice of the person sitting closest to you over the din of shouts coming from all sides. It takes time to decipher, more time than I had during my visits.

Despite all the crowding, don’t expect to see anything unruly. Bartley’s work is very composed. The clipping-collage of images and quotes from sundry sources is an irresistible aesthetic. This way of working may sound familiar; I’ll leave the art-historical references to your imagination. But I will say that Bartley’s image and sound-byte sampling is getting better at asking us to appreciate the present context they create rather than drawing us back to the published sources from where they came.