Wine as Lens, Paint as Shield: Off-Leash Area’s Philip Guston

Lightsey Darst reviews the remarkable Off-Leash Area's "Philip Guston Standing on His Head / Standing Philip Guston on His Head" that ran at Our Garage, August 19-20 & 26-27.

“Philip Guston Standing on His Head” and “Standing Philip Guston on His Head” are two different propositions (as Off-Leash Area’s Paul Herwig and Jennifer Ilse may realize). The first implies the actual person, Philip Guston, American painter of abstract works and cartoony mauve-pink work scenes, enacted on stage in a headstand, with the emotional implications of this acknowledged and dramatized; it implies Musa, Guston’s wife, reading from her journal, pressing leaves, making sandwiches; it implies Guston’s life on stage, explained to us.

The second, “Standing Philip Guston on His Head,” suggests using Guston, a turned-about, head-standing, abstracted Guston, as an archetypal artist-figure. In this second proposition, Guston’s life is not the subject of the performance, but the material, setting, pretext; his work is not explained by the performance but used by it to create new work, his symbols not explicated and unraveled but turned to new use, borrowed, transformed, revived.

The first proposition, Philip Guston as Philip Guston, performance as biography, isn’t that interesting. We get the most insight about the real Guston from excerpts of Night Studio, Musa’s memoir, read by Jennifer Ilse; while Ilse reads well, and the quotes are poignant (of a disappointing painting, Guston felt that it “looked as though it could just be peeled right off” the canvas), this staged reading feels secondary, uncreative. And the drive of this narrative goes nowhere new: it’s a tour of tortured artist land, with the usual stops at childhood trauma, adult alienation, marital miscommunication, alcoholism, and chain-smoking.

Ilse and Herwig toss and turn as Musa and Philip in bed, Musa clinging to Philip, Philip using Musa for a pillow, Musa putting up with any contortion to be near him but Philip unable to sleep until he has his brushes in hand—it’s a moving scene from an unequal artistic marriage, but it’s undermined by the literal narrative that encircles it. Finally, this narrative seems to imply that Guston’s desire to retreat into his imagination is an artist’s version of suicide. Herwig and Ilse have turned their garage, where people ordinarily store cars and sometimes put themselves out of their misery by breathing carbon monoxide into a theater, a place of lively invention; surely they know better.

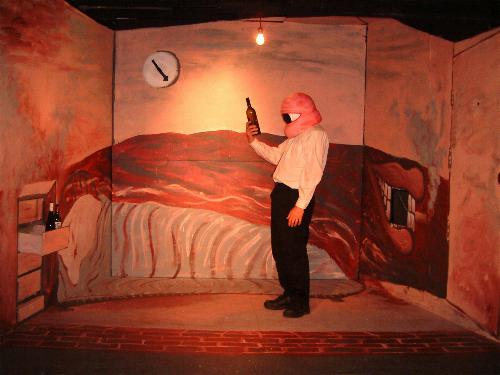

But go back to the fork in the road and take the second proposition. Here Guston’s imagery comes to new life: a cigarette is not a cancer stick but an object of compulsion, a sandwich is not something to be eaten but a sacred object, wine a lens, the brush not just a brush but part of the body or mind with which one touches and explores. Seen this way, the performance dives further and further into the imagination, not particularly Guston’s, but the artistic imagination expressed through the metaphor of Guston. Guston’s mind is Off-Leash Area’s playground. Ilse and Herwig turn Guston’s paintbrushes with circular splotches of color into shields with which Guston and his imagination enact ritual combat. While at first we see Guston eating a “real” but clearly fake sandwich (hyper-green lettuce, red tongue of tomato), by the end his imagination has handed him a giant totem of a fake sandwich. This fake real sandwich, fake fake sandwich/art sandwich is part of a doubling and deepening method through which Ilse and Herwig create a symbolic language. We wind up in a new place of perception, saying something that can only be said through this language. See “Philip Guston” this way and it doesn’t lose emotional impact; instead, it becomes more complex, less predetermined, more compelling.

Theory aside, what are you actually going to see if you go to Ilse and Herwig’s garage? Not much actual dancing: no leaps, turns, or combinations, anyway. The sleeping scene described earlier is more active and more densely choreographed than the rest of the performance. Yet I’d still call this dance because ballon, the dancerly illusion of weighted weightlessness, of a material object almost immune to gravity, manifests itself everywhere in “Philip Guston,” especially as we get further into Guston’s imagination. What’s dancing, however, is the marvelous set. Drawers pop out of the wall, black cartoon clock hands tick, the art sandwich, wine bottle, cigarette, and paintbrush march across the back of the box stage, all in perfect timing to quirky and entirely fitting music by the Lonesome Organist.

Ilse, in her second role as Guston’s imagination, bounces and wears white Mickey-Mouse gloves as she gestures in big-suit mascot-costume style. Meanwhile, Herwig plays the artist as an observer, a curious man whose curiosity burrows inward rather than zooming outward. I don’t know whether Herwig often crosses his eyes in real life (imagine the unnerved cashiers), but on stage he keeps up an obsessive near-sighted stare, his eyes moving back and forth but never quite seeing the object as object. In fact, not seeing the object as object seems to be what “Philip Guston” is about; the object, whether it’s Philip Guston’s life or a cigarette, isn’t what’s most interesting. Herwig and Ilse aren’t putting everyday gestures on stage to ennoble them, as some dance performances do. Instead, they’re putting the imagination on stage.

Thus the ballon: the inner world is inextricably tied to the outer, but also nearly free from its constraints. I can’t quite explain how it’s fascinating and meaningful to watch a lightbulb on a long cord spinning around and around Herwig as it’s slowly raised until it spins around his head and he follows it with his eyes—which is just why this performance is worth seeing: “Philip Guston” makes its own world.

You might expect an element of regret in a garage performance—a wish that the performers had more space, more resources. That’s not the case here. I can imagine Herwig and Ilse creating something for a different space (why not Northrup Auditorium?), or for no space at all (performance by the side of the road?), but this particular show doesn’t need more. For “Philip Guston,” Our Garage is a fully developed theater.