We Are Better

Davu Seru on the state of the Twin Cities jazz scene—on its competing mythospheres and various hustles, its labor given and co-opted, and ways we, audiences and artists alike, might all do better.

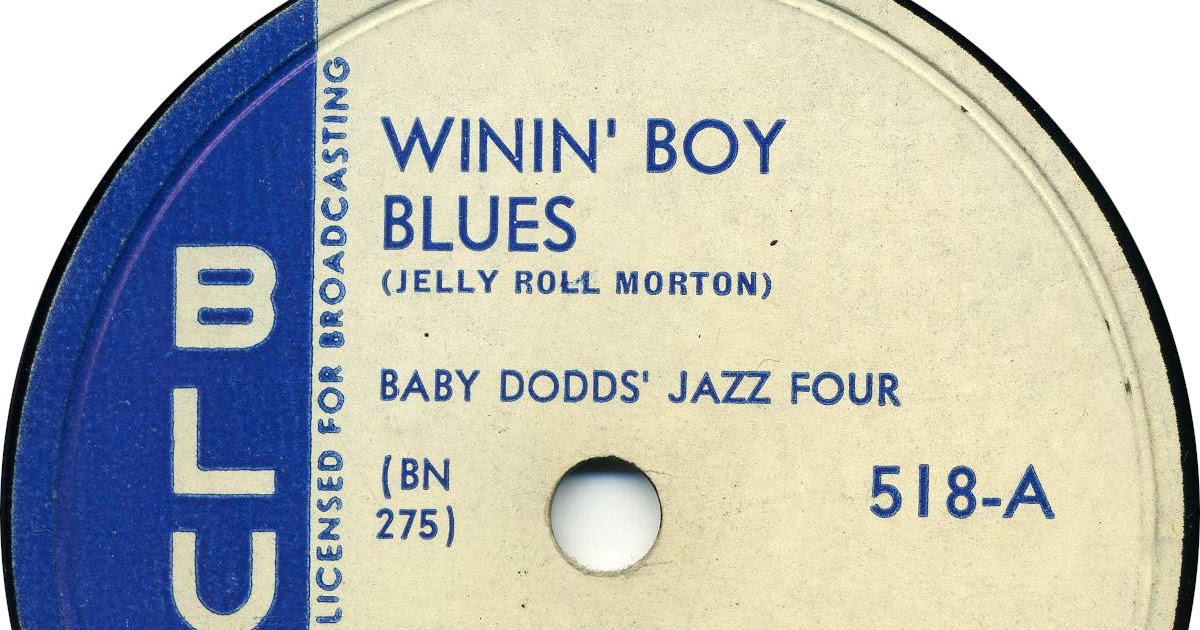

I’m the winin’ boy, don’t deny my name.

Jellyroll Morton, “Winin’ Boy Blues”

I was asked to write about jazz. I hope that, once I’ve first served up this palate cleanser, I am able to simply write about local concerts, recordings and musicians for their merits and in their broader cultural and historical contexts. But first things annoyingly first.

Jazz was labor stolen from the bosses. But, even still, the serpent’s mouth and tail and all that, since it has also always been co-opted by economic forces that it has had to respond to. Jazz remains both a paradox and a heroic burden.

I am very lucky to play with the best musicians that the Twin Cities offer—musicians who would do well in any scene that you’d drop them into across the globe. I am also fortunate to, on occasion, travel and play abroad with musicians of equal caliber. What we and our audience share is a group fantasy that requires faith in the Mystery, faith in the heart of jazz. Which will sound odd to you, if you’ve been sold on the materialist line that, in jazz reality, everything is already apparent. That taking part in this music and its rituals is just another thing to do in the realm of the real. In that case, you’d take the fact that all value is arbitrary as an occasion for despair.

Among the musicians I’ve spoken with, there is a general discontent, even among the Europeans who survive on government subsidies. We believe that musicians do not take enough responsibility for the music. We complain in private about how we are treated by venues and tastemakers, and by the musicians who don’t turn out to our gigs, but who ask for favors. We complain about having to compete for resources with musicians who arrived at jazz by accident, when a seasonal job down at H&R Block, or collecting baseball cards instead of records, would have proved just as purposeful.

We complain about how the Law of Jante seems to apply to local audience, musician, and booking agent alike. Some of us complain about the absent black audience. The all-stars, the outsider-friendly festivals, the #alllivesmatter approach to granting recognition, the policing of complaint.

We musicians perform in a realm of competing mythospheres, competing cliques and fetishes. A handful of players have made the best use of this midsized pond by primarily marketing their talents in NYC and abroad. Settling for a different sort of prestige, the professional, white-collar class is happy to play to accompany you at mealtime. Then there’s the numerous repertory players who have settled for imitating their way into the tradition; the punk and hip hop generation free boppers that I am partly allied with whose hipster-come-lately naiveté annoys the old Loring Pasta Bar once-upon-a-timers; the vocal and jazz pop and fusion folks making do as entertainers; the Selby Jazz Fest celebrating a bygone place and time in ways that remain illegible to me; the big band jobbers fighting both ageism and mediocrity; the numerous players who recently landed here after graduating from music college who will get what they can before heading East; the black and white avant-garde that you have only half heard of whom the contemporary music and art curators could not care less about; the high school-aged players currently being spoiled with praise and the few octogenarians and older who came up with the wonderful Leigh Kamman.

If I’m missing someone, it’s because it is easy to do given all the generational, class and aesthetic divisions that expose the lie that jazz musicians are all “joined at the hip.” These are fissures that Great Day in Twin Cities jazz photos distort and conceal. And it’s a distortion that leaves the people who contribute the most to the art form on the outside, with the hustlers who have been anointed by the festivals, and by The Dakota and Vieux Carre clubs, on the in.

These are fissures that Great Day in Twin Cities jazz photos distort and conceal. And it’s a distortion that leaves the people who contribute the most to the art form on the outside, with the hustlers who have been anointed by the festivals, The Dakota, and Vieux Carre on the in.

In short, if, as writer and cultural critic Albert Murray says, jazz is the “adequate metaphor for the truth of the American experience,” then one should not be surprised that American jazz is so forcefully displaying its neo-conservative ass. That there is how we are all truly “joined at the hip.” For real.

We Twin Cities jazzers no doubt inherit a world and work ethic of German, Scandinavian, Jewish and, recently, Hispanic descent, who bring to black music their own ideas about the folk artist as cultural worker, but who also done melted into the pot just enough to be suspicious of art and artists.

We’ve replaced taking responsibility for this scene with bitter competition for gigs and recognition. It’s a bitterness that musicians feel justified in living out, citing the competitive underbelly of the tradition, forgetting that bitterness was necessary because, if you were black, resources were already so scarce that it was a matter of life and death. In our current context, that bitterness reads more like a compulsion of the unsatisfied ego of a musician who sacrificed the middle-class comfort that was his birthright for a career in jazz.

Rather than a sense of responsibility, there is too much bravado in the absence of exceptional musicianship. But such is the way of insecure brats and bullies, and my ‘hood upbringing reminds me where folks like that end up, when them with far less notice Mr. Lunchables and Sunny D. putting up a front.

But I did not set out to write this in order to put my authenticity on display. There is no outside; we are all complicit. For instance, if I get my way, my particular mythosphere survives on grants—a world that rewards bullshitters and excludes those who lack the training to market their work. Still, one thing we musicians often say about the Twin Cities is how great it is to live in a place with so much arts funding. Resources are not nearly as scarce as was the case with our black brethren of the cutting contest era. So, my only advice to the institutional powers that be is this: instead of spreading yourselves thin and distributing support as widely as possible, so that funders get the most diversified return on their investments, you should direct audiences to the most innovative work on the scene. And if you don’t know where it lives, ask the musicians. Such a shift would perhaps urge those that get by on mediocrity to step up. Surely, this would be impolite—presumptuous, even. But at least it would suggest that those of us who claim to be hip know what we are talking about when we talk artistic merit.

Most of my complaint here is reserved for Twin Cities jazz musicians. And, to you, I say that doing better than the sorry bunch of motherfuckers we currently are might include the following:

- Support other musicians by showing up and paying the cover charge

- Start and promote a performance series

- Use social media to support other musicians

- Book shows where black people live or frequent

- Be discerning, not petty

- Learn the difference between imitation and innovation, and expect to be compensated in kind

- Know that irony and cynicism are a type of defeat and advance nothing

- Start a label

- Wait your turn

- Respect your elders until their egos fail to match their playing—but, still, cut them some slack, because things have been bad for a while

- Complain openly and unapologetically about things that affect more than just you

- Doubt yourself and work to be better

Stop asking for permission! Act like you love this thing we do, and put in at least as much as you have taken out. We will all be better off for it.