Wants to Be Your Dog: “Untitled” at Soo VAC

Collier White surveyed the mixed results of the Soo VAC "Untitled" show--their annual juried exhibition. There's much to praise and blame, a lot of visual interest, stuff that'll inspire talk. Show is up through August 28 at Soo VAC on Lyndale.

At the opening of the Soo Visual Arts Center’s fourth annual juried show, DJ Lori Barbero’s lifted her headphones to field a question from a patron. “What, Iggy by himself’s not good enough for you?” she replied and resumed dancing. Earlier in the day, squirrels were down from the trees in a in a heat-evacuated Loring Park, cooling their bellies on the grass and sighing, “I wanna be your dog.” The London Police were preparing to release information on the number of shots used in their recent installation piece, Underground, and in a Minneapolis gallery, there were a lot of embroidered shirts milling around, trying to decide on small samples of familiar and unfamiliar work.

There’s plenty of interesting work in Soo’s Untitled 4. In two giant, scroll-like paintings, Janet Lobberecht puts herself in a trance by writing cursive words over and over again – like a junior high student whiling away study hall with a crush on a concept. Then, she works the resulting patterns into paintings. Bringing a similarly repetitive mechanics into the sculptural realm, Kristina Estell’s installation piece, Ground Cover, is a stony little egg’s nest that would sit sweetly across a tiny picket fence from one of Yayoi Kusama’s phallic gardens. Ground Cover and the show’s other installation piece, Trever Nicholas’s prizewinning Bulboids, unfortunately suffer from the gallery’s unevenly colored floor and spatial challenges that make them look, disarrayed.

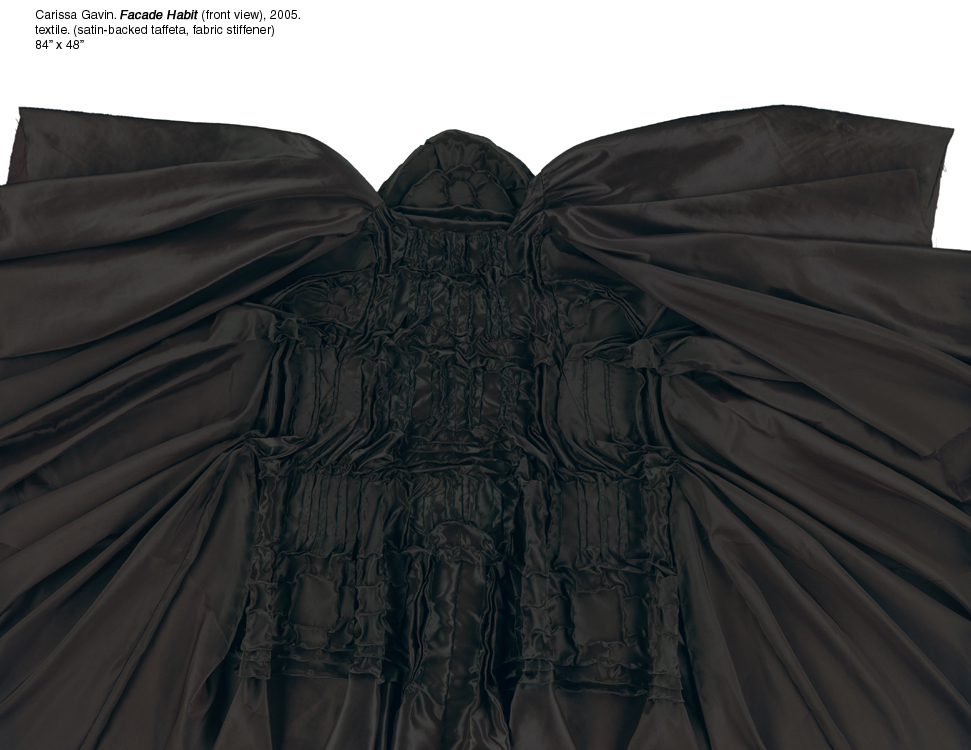

At the back wall of the gallery is a nun’s habit is fanned out in a glass case. It looks like an attacking angel, pinned to a board like a butterfly. In its glass case, Carissa Gavin’s Bad Habit, San Zaccaria is singular but taxonomic, and it strikes me as cleverly aggressive. Stitched into the garment, an architectural drawing of the San Zaccaria church gathers the fabric into tiny bones like bat wings. Later, I found that Bad habits, as Gavin calls her current work, involves installation pieces and performance art. Like much of the work included in Untitled 4, the single work on display is only an illustration. The small sample is a placeholder for one of 22 artists chosen by jurists Clarence Morgan and Michael Hoyt for Soo’s fourth annual juried show.

Further, Gavin’s work – she explains in a lengthy and jargony Artist’s Statement – is a part of an ongoing Masters of Architecture thesis that has something to do with the actual history of sexual practice in the Italian convent church of San Zaccaria, something to do with transgression and a lot to do with Foucault’s ideas about genealogies. Thus, the work is ultimately subordinated to the role of illustration: it suggests Gavin’s body of work which in turn supports Gavin’s thesis, and my immediate experience of it, as a site of visual pleasure and awe is (ahem) not privileged by Gavin’s theory. Even the sexuality here is rarefied – tied up in an exclusivity that investigates pleasure only after it investigates oppression. While Gavin’s work might decry the sexual oppression of her chosen subject, she in this case duplicates the replacement of immediacy with ritual. The cloak is not for you, nor about you, and certainly not available for a tumble.

Much of the work on display is, like Lobberecht’s and Gavin’s, large and imposing. I know Christopher Shields, and I had come in part to see his work. Like Ben Olson’s paintings on the opposite wall, it depicts large human figures, and like Olson’s, it stands in contrast to a dominant trend of postmodern recursivity. Shields’s two six-foot photocollages depict nudes wrapped in bedsheets and soaking in bathtubs. By the standards of this show, Shields’s pieces are a little bit straightforward – we know immediately that we’re looking at erotic horror. The inclusion of body hair and gooseflesh reject the plasticity of pornography, yet Shields’s collages catalog and disarticulate his sitters in a serial (killer’s) investigation of intimacy With just two of these collages, it’s hard to tell what is going on. To overcome the brevity of his presentation (one of those on display here is a collage of two other collages, with genitalia partially removed to satisfy the sponsor), Shields handed out pamphlets with images of the rest of the work in this series, and here the humor of his work takes shape.

On the opposite wall, Ben Olson’s paintings first strike one as an amalgam of his influences. The gilding immediately evokes women’s dormitory favorite Klimt, the clenched hands suggest Schiele, but Olson’s big-brush acrylics have a painterly confidence that’s striking. In three oversized portraits, he depicts lovers in a moment of anger and dismay. His fisted hands hold a shattered glass stem, hers claw at her cheeks like a silent film star.

While Olson expresses the immediacy of the present through his use of fast-drying acrylic paint, Euclide’s now ubiquitous paintings employ a kind of graphic exactitude overlaid with numbers derived from events and formulas. His landscapes include randomness, such as the number of times a door opened or closed during his work, or the address of an element on the periodic table. And with their now-familiar mixture of perspective and flatness, Euclide’s medium-sized paintings are becoming as alienated as the scenes he conveys. His limited palettes, which a year ago struck me as the muted tones of urban sprawl, have quickly been adopted for the bathrooms of this year’s warehouse lofts.

The samplings in these juried shows – just a few linear feet for each artist – turn the event into a recital. While last year’s Draw seemed to explode with ideas, this show has neither the breadth of that smorgasbord nor its spastic impulsivity. I recall that Draw, which opened shortly after the crushing election results, exploded with possibilities that seemed to defy the perpetual inanity guaranteed by the dismal political outcome. With this show, the nausea truly seems to have set in.

Artists who showed well there show less vibrantly here. Megan Vossler, whose watercolor and pencil sketches follow the emotional and social content of impressionist Mary Cassatt, shows some of the same pieces that were in that show. Yet outside of the context of the Draw exhibit, the unfinished quality of her work is a little puzzling. Vossler’s sense of her subjects is intuitive and quietly engaging, but what her work gains in immediacy it loses in permanence.It’s likewise with Andrea Carlson: Her boldly colorful but intricate mixed-media paintings struck me as one of the newest directions represented in the show. Their anthropomorphic characters are like the graffiti glyphs of a new urban Indian. Yet Carlson seems not yet to have settled on a medium that will match her intriguing content. Thus the works seem a little tentative and, in places unfinished.

In the end, the show seems to be summed up by Jesse Hemminger’s motorized mobile, To and Fro. Cast plaster fingers on slow moving pistons elevate and lower their piece of a ceramic tabletop. The clever machine churns endlessly while the tips of the fingers slowly erode.