Vol 1, No 1: American Tourist: Aaron McLeod at the Duluth Art Institute

Suzanne Szucs views a set of images shot by an American soldier in Iraq: she finds them both useful and moving.

In 1955 Edward Steichen, then curator of photography at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, organized a landmark exhibition called “The Family of Man.” Hailed by some as groundbreaking, rebuked by others as simplistic, the exhibition, which consisted of over 500 photographs from 68 countries, was a post-war plea for world unity. The thesis was simple: we are all cut from the same cloth and want the same things – love, comfort, stability, happiness … What else should one hope for in the atomic age, than that we all try to get along?

Cut to 2006 and it seems as though we are further than ever from getting along. Fundamentalism of all sorts is on the rise and we have trouble communicating with our neighbors across the street, let alone at the other side of the world. Not only are we dismayed by this lack of cohesiveness, but also we despair at what to do about it. Our government seems to step blindly forward, or to the side, or backwards – it’s hard to tell. We are exhausted, exasperated and seemingly out of options.

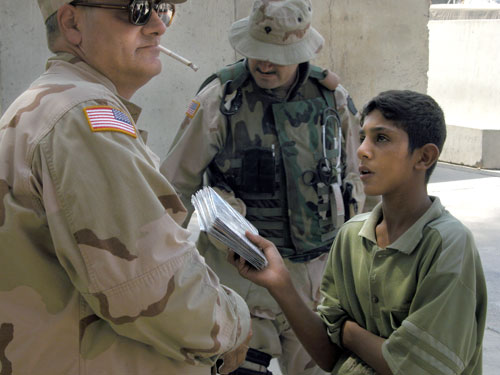

Enter Aaron McLeod with his exhibition at the Duluth Art Institute, “An American Tourist in Iraq.” A member of the National Guard in Duluth, McLeod served with the 477th Medical Unit in Southern Iraq during 2004. During that time he made himself available to serve with the “Hearts and Minds” program responsible for distributing humanitarian aid and school supplies donated by Minnesotans. Never seeing the kind of combat that we get glimpses of from the media, McLeod found his time there a surprising opportunity to stretch himself as a photographer. At the exhibition opening, his Commanding Officer told me that McLeod would volunteer for trips, being dropped off at a site, help out in any way that he could, in the meantime photographing, later to be picked up by his unit on their way back through.

It’s apparent that McLeod shot much more with his camera than he did with his rifle. That most of his subjects on display are portraits of the individuals he met during his assignments brings home this irony. It is a startling reminder both of the Family of Man thesis and what’s at stake: our moral obligation to communicate rather than destroy. Steichen thought that by showing the uniformity of global humanity we would learn the superficiality of our differences and choose to tolerate these differences rather than create conflict over them.

Likewise McLeod chose to “get to know his subjects,” finding a way to intimately communicate with these people through art. Even as he writes in his artist statement about the cultural differences he observed, his photographs of individuals break this down. They smile, laugh and open up for the camera. These people are able to look past the uniform, a definite symbol of power, and into his lens, openly. McLeod writes eloquently about the conflict, “Arriving in full armored vehicles with loaded weapons, we had to somehow appear benign and aggressive simultaneously… I sensed that we were more apprehensive of them than they were of us.”

The photographs that make up the third portion of “American Tourist” bring this complicated relationship to bear. The images in this section of the exhibition present less clear, more conflicted issues. Here we see images that emphasize the beauty of abstraction that McLeod is attracted to made out of the damage caused by the war. McLeod writes about a building that had been transformed into a barracks for soldiers: “Enemy mortars had destroyed the place so quickly that the occupants didn’t have time to gather their possessions before evacuating. They left behind clippings and posters on the walls. Fire melted the paint into a drippy montage of memories and ironic imagery.”

But who is the enemy and who the victim? Having just looked at a wall full of Iraqi portraits, I was surprised that the images McLeod had made were of wives, children and the inevitable soft-porn clippings belonging to American soldiers. Within the exhibition the disparate images face each other, neighbors looking across a great divide.

Likewise, an almost abstract image of a shattered HMMV passenger window left me confused – was it a U.S. soldier or a prisoner who stained it red with blood? McLeod’s image of Abu Ghraib, American flag in the background, is dark and ominous, although the structure of the composition is formal and orderly. We see no horrors here; only the darkness tells us that something is not right. “Big Brother” style stencils imposed by Saddam have been countered with hand drawn U.S. responses – is the answer to Saddam’s menace really “I am a pussy”?

It is in this section of the exhibition that I sense McLeod’s feelings of alienation. It is clear that it is the victimizer who is not represented here. The Iraqis, the soldiers – both groups are the victims of a war machine out of control and irrational. It is this underlying senselessness that makes these images complicated, and the entire exhibition powerful, despite there being no graphic images of violence—or maybe because of this.

McLeod also presented video he had shot during his trips. Standing next to some National Guard members who were recognizing themselves in the clip, I turned to get their impressions of the exhibit. McLeod’s CO, David Nyback, offered, “… it’s good to see some of the good stuff emphasized…I am proud of what he has done here.”*

To my eyes, it wasn’t that “good stuff” was being emphasized or even promoted by McLeod, because it is his statements that clue me in to the where and how of his portraits, not the photographs themselves. Frankly, they could be of any people, anywhere — and that’s the point. “An American Tourist in Iraq” gave me the opportunity to get beyond myself, to look objectively yet compassionately across the world at a group of people who are not so very unlike me.

*I must add a disclaimer that McLeod was one of my photo students at UMD and I am proud of him too.