VISUAL ARTS: (10,000 Arts) The Man from Hamburg

How Frank Sander wound his way through several art mediaand into an obscure corner of China.

AS YOU WALK DOWN THE NARROW HALLWAY into Frank Sander’s sunlit studio in Lowertown you’re greeted by an entryway table piled with cables, cast-off camera bits, miscellaneous video equipment, and a couple of discarded microphone heads.

On the walls are personal treasures the German-born artist has picked up during his twenty-odd years of travel. He takes down a recent prize from a wall near the galley kitchen: a weathered, conical straw hat he bartered from a farmer on a recent trip to China’s Yunnan province. “Can you see the sweat stains along the strap here? Look at the fine weaving work; the swirls and patterning in the straw are just stunning. I love that this bears the evidence of his labor, the time he spent in the fields,” Sander enthuses. “I think it’s just beautiful, it’s so human.”

Sander studied carpentry and architecture, along with visual art, in Germany but he’s an itchy sort of artist, resistant to the fetters of just one discipline. Finding carpentry and architecture to be too precise and measured, he turned to sculpture and painting. He’s also noodled around with filmmaking and photography since childhood, experimenting early on with Super 8 cameras, and graduating over time to videography and digital photography.

In his twenties Sander wandered throughout Europe, living in Spain for a time, then Holland and Denmark. On a trip home to Hamburg for Christmas in 1979, his passenger train was caught by a week-long blizzard. “After a couple of days, I started to look around for ways to pass the time.” He recalls wryly, “I kept thinking, surely there’s young woman around here who needs some company.”

You can guess the rest: a fellow passenger was an attractive American. They hit it off and Sander followed her back home to Minnesota, where they were married. That relationship eventually fizzled, but his affair with the North Star State did not.

In fact, Minnesota’s thickly wooded landscapes, especially the wilds of the Boundary Waters, have indelibly marked his artwork. Sander may be best known for his critically hailed installation, Human Nature, which premiered at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts in 1999 and also showed at the Daum Museum of Contemporary Art outside Kansas City. In Sander’s landscape, fish enrobed in resin hang from the frame of an upturned fishing boat; and scores of found beaver skulls sit in government-issue file boxes in witness to the destruction of their habitat. The installation was a sort of sculptural reliquary for denizens of the upper Midwestern landscapes displaced by industrialization and sprawl.

Sander, however, now has mixed feelings about large-scale public art. “It takes so much time and money to put something like that together. No one really buys work that large so, in the case of Human Nature, it sat around on my property deteriorating for years just getting in the way. I’m more interested in actually making artwork than in shopping my artwork around.”

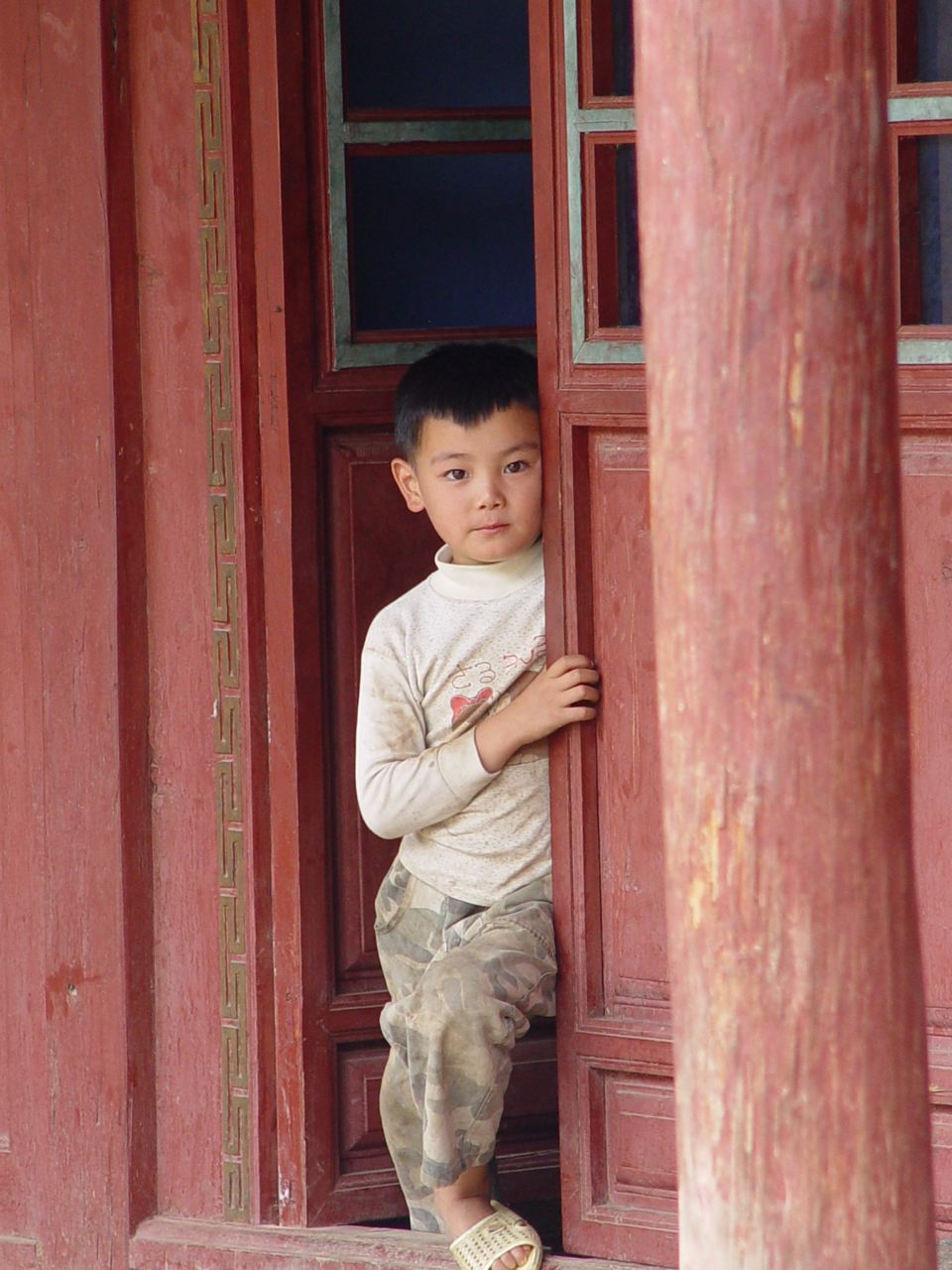

His current passion, videography and film, is a more streamlined endeavor which marries well with Sander’s wanderlust. His most recent project involves documenting the tribal minorities and austere beauty of the Yunnan Province, situated in the mountains near the Tibetan border. Typically for Sander, he arrived at this latest work through both luck and a Zen-like acquiescence to the vicissitudes of his curiosity. He stumbled upon these insular mountain enclaves last year while sightseeing with a friend in China, and he became intrigued by their singular cultural histories. Wanting to find out more, he struck up a friendship with a local university professor familiar with the area, who introduced him to some locals.

Sander found himself smitten with the people and communities he found there, poised between agrarian life and industrial modernity. After just a couple of trips, he was hooked. Now, armed with just a camera, he’s been returning to these villages every chance he gets. Sander’s footage from time spent in these villages is immediate, allowing the viewer compelling, over-the-shoulder access into these mountaintop villages. You feel as if you’re going with him into the homes of a boisterous young dancing troupe, or that you’re following alongside him as he wanders down narrow village streets on a brightly lit festival night.

With the ongoing collaboration of his Chinese partner, He Lujiang, Sander is now beating the bushes to raise money in support of an ambitious film project which would chronicle these tribes’ quickly disappearing customs. He argues, “We have the opportunity to preserve something of this way of life before it’s gone. Imagine how much we could have gained if we’d been able to do something similar to capture a record of Native American life before the days of reservations. This is the chance of a lifetime, but we need to move quickly. These are communities on the cusp of modern life, and every day they lose a bit more of their heritage to the conveniences of new technologies. If I can document their way of life, I’d like to post the whole film for free online. He Lujiang and I want their chronicle to be our small contribution to the world.”

The medium may vary, but Sander’s consistent theme is preservation. His is the proverbial (and literal) voice in the wilderness urging us not to forget what we once were and to be mindful of the natural wonders being sacrificed for the manufactured comforts of modernity.