Untitled 6 at Soo VAC: Nothing Promised That Is Not Performed

Untitled 6 at Soo Visual Arts Center, opening Friday, June 22, is the latest incarnation of the gallerys annual exhibition. Its 20 young artists were juried into the show by painters Andrea Carlson and Jaron Childs, who have shown at the gallery.

Other “Untitled” juried shows have had art-historian or curator judges. Those shows have also been less quirky, and to my mind less interesting, more riddled with easily traced influences. It’s possible that the curators and art historians saw art as strategic, artworks as evidences of strategies; this show puts a kind of well-knit physicality in place of such analytical threads . The current show seems less canny, less self-consciously “smart”—but far more satisfying, and certainly no less intelligent.

I can’t write about all 20 of the artists in the show, but the standouts – Joe Sinness, Mason Eubanks, Audrey Bernard, Sarah Thibault, Garrett Perry, Jonas Lindberg, and Katherine Redford—all present work that has good reasons to ask for your engagement. The pieces cover the ground between their intention and your location; they don’t assume virtues that they don’t perform.

Joe Sinness, whose drawing technique is very fine, parodies his own skill in Apocalyptic Dolly–in which Dolly Parton is a deity surrounded by birds and thunderbolts, worshipped by a cuddly and very real trembling bunny. He seems confident that his skill will induce us to follow him beyond the mere joke and into the strange realm in which this scenario is for real, and in this he would be right.

Mason Eubanks makes sculptural forms that refer to paintings but that squeeze out around that category. His pieces are fat asymmetrical rectangles that hang on the wall, but their pebbled surfaces are covered with tiny spirals of Sharpie ink. What from a distance looks like a Jetsons-cartoon painting knitted out of mohair is, on closer inspection, a world of little whirls. The scale surprise doesn’t fail to delight.

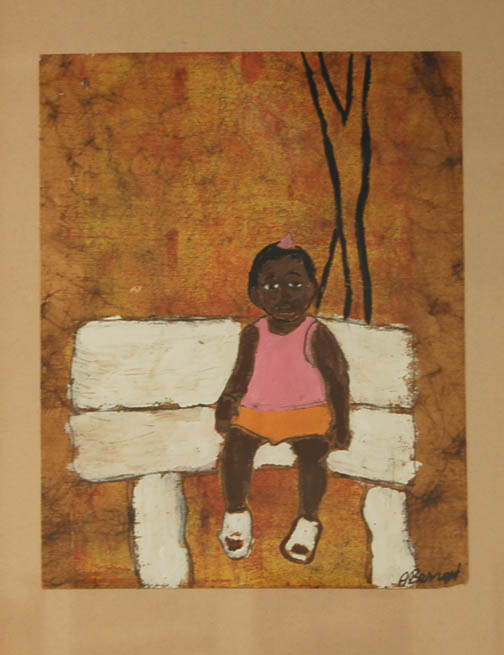

Audrey Bernard does straightforward portraits of people she seems to know—Miss Chimp, David, Davia, others—but imbues them with what painters can give. She sees on a different plane. I don’t know if it’s more truthful or less—but it is different, and it enables us to see differently too. Having this doubled vision suddenly makes the world three-dimensional—it’s like, having lived with one eye all your life, you suddenly are granted binocular vision. Things jump into high relief. They become themselves.

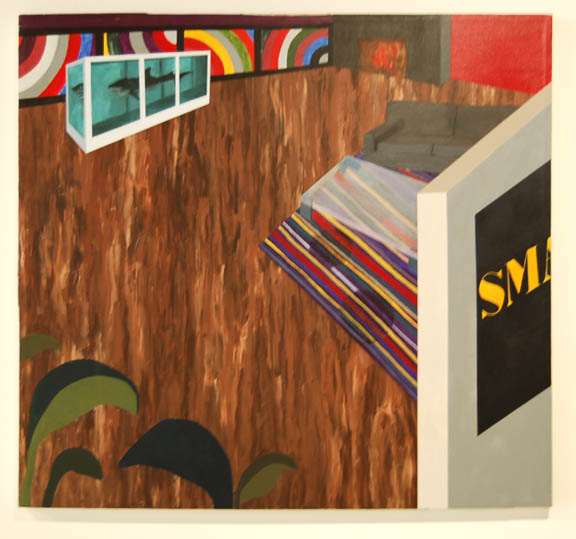

Sarah Thibault’s work here depicts “the homes of the collectors.” After a couple of decades in which collectors have been at least as influential in the artworld as artists or critics—think of Saatchi!—this bit of wit is more than pointed. And the cubistic treatment of these “homes”, so like David Hockney’s early work, and even reminiscent of Saul Steinberg’s cartoons, sharpens the joke, makes it formal, and spreads its commentary beyond the current moment. They’re also really handsome paintings.

Garrett Perry, like Audrey Bernard, is a painter who relies on the process of painting to make his imagery revelatory. His titles (Maypole Madness, Weren’t We Angels?) are a little too arch—they make it seem that he doesn’t quite understand the joyous gravity of his own work—but his hand will no doubt save him yet.

Jonas Lindberg is one of a minor wave of fiber artists on the current scene. His crocheted red sleeves and hoods for deer skulls and spines speak of the imbrication of line, of how a line describes something, how it weaves in and out to create a body. Fiber’s obsessional qualities—its repetition, the time it represents—are good in works that use the dead body of another being. That kind of dwelling-on, dwelling-with, tends to indicate that the use is in good faith.

Katherine Redford also uses traditional fiber techniques, but she uses metal in her obsessive weaving and stitching. Her objects, though small, have a kind of stately scale, an odd ability to make room for themselves by seeming to have already existed, before she dreamed them up. This quality of . . . what is it, a phenomenological mandate? is something that good sculpture tends to have. Such works are images of the preexisting, embodiments of a state of affairs that existed before they were made. Such a sculpture is made, apparently, to be a house for an entity that is already alive. It’s a bit uncanny, and mysterious.

There are many more fine works in this show. It opens with a reception on June 22, 7-10 pm.