Unnatural Nature: Tangle at Thomas Barry

Mason Riddle thinks about David Lefkowitz's show "Tangle" at Thomas Barry Fine Arts. It's intriguing, and it's up through April 14.

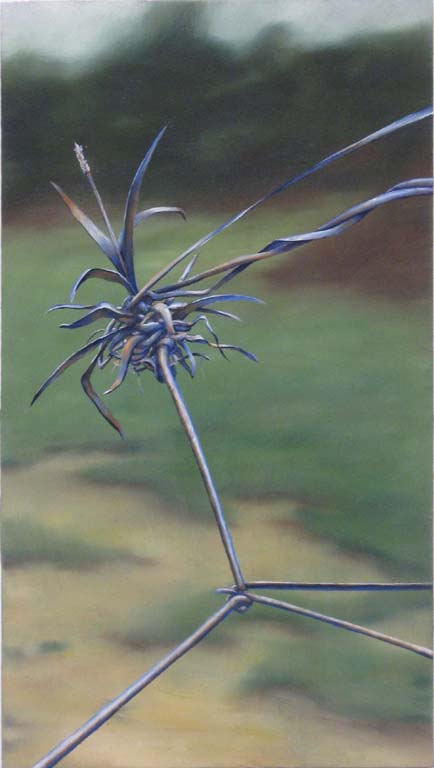

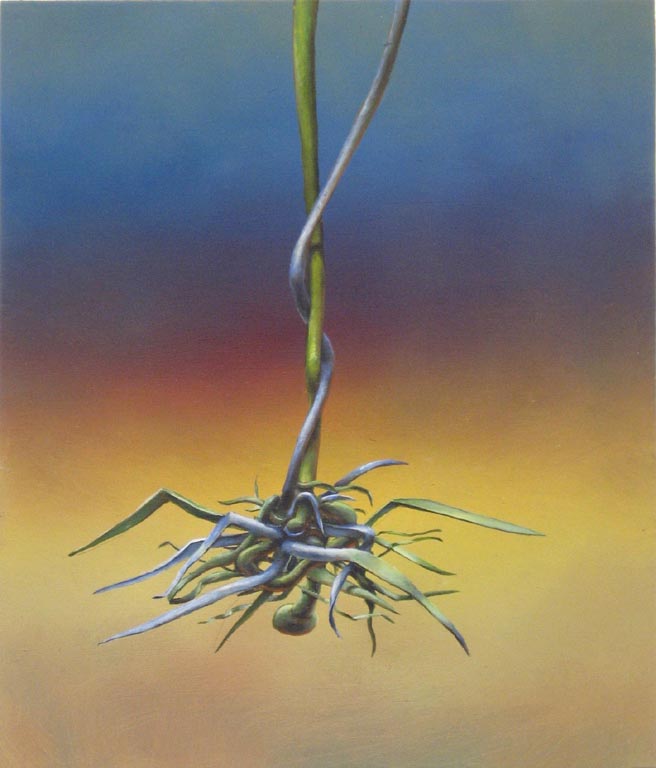

On a recent cloudy day, David Lefkowitz’s paintings looked positively brilliant. Brilliant like small, jewel-toned Florentine panel paintings of saints shimmering in a dark cathedral. But these were not paintings of the holy. The devotional subject of each is the unnatural commingling of electrical conductors and plants, which are dueling it out, big-time, in an indeterminate realm. Modest in scale, unframed and luminous with meticulous high-gloss surfaces, the paintings are executed in an uber-realist style that anthropomorphizes both contenders. In one painting a small plant is taking an electrical connector right through its marigold-like head. In another, a bright green stalk with branches is slowly being wrapped in multicolored wires and, in several others, plants and cords are simply strangling each other.

Art historically, the odd pairing of plant and cord conflates the traditional genres of botanical print and still life into a single, unorthodox hybrid. However, the exhibition’s title, Tangle, indicates that more is at stake than the detailed study of plants and objects. These are not pretty plants, but weeds and grasses that spike up in August along the driveway or the garage foundation. The cords could be found in any home or office.

A metaphorical reading of Tangle might see the aggressive entanglement of plant and cord to be a portrait of desperate mismatched lovers or, perhaps, two irreconcilable tribes at war. A more pedestrian reading is that these works address the ages-old conflict between humankind and the natural world, but with Lefkowitz’s expected subversive hook. Unlike the sublime nineteeth-century paintings of the Hudson River School or the chilly works of Caspar David Friedrich where man is portrayed small, weak, and in awe of nature’s power and vastness, Lefkowitz takes the conflict in a different direction. In Tangle, man is no longer overwhelmed by nature. Rather, it is man or his byproduct – the detritus of human technology – that is adversarial to nature. By Lefkowitz’s scorecard, technology is winning.

Lefkowitz has long explored the topic of human intervention upon nature. Tangle builds on an earlier series of work called Flora:Introduced Species, which also put a microscope to the oil-and-water relationship between technology and nature. But in Tangle Lefkowitz takes the expanding conflict one step further. Not content with his repurposed type of genre painting or the ongoing human-versus-nature wrestling match, Lefkowitz twists his critical knife one turn further. Unlike the previous Flora works, in the Tangle series the paintings’ backgrounds are no longer simply neutral backdrops for the conflict. Here, some the backgrounds have been painted to suggest an endless sea or a timeless, eternal space glowing with light and atmosphere. Heaven? Others depict a grainy out-of-focus background, as if the works were not paintings at all, but common photographic snapshots, legitimizing the conflict as real. Also, by painting weeds, plants known for their rampant growth, instead of more exotic flora, Lefkowitz constructs a parallel narrative to the out-of-control growth of technology. If, initially the paintings seduce through the veneer of beauty and an offhand sense of humor, the dark side quickly subverts this appeal. The paintings suggest, “I may be beautiful and full of artifice, but this conflict is real.” It is no longer so easy to see where nature stops and human engineering begins.

It has been suggested that although beautiful and technically facile, Lefkowitz’s paintings are one-dimensional. This is an inaccurate reading of his work, unless a painting series of any single topic is one-dimensional, whether it is exploring self-identity or the Stations of the Cross. At the core of almost all of Lefkowitz’s work is a large, usually difficult topic, which he addresses through impressive technique, irony, and often beauty to complicate the reading of that issue. For example, his earlier works that included images of trees, painted wood grain, and lumbering were not about wood or forests but about clear-cutting, the environment, and international trade. It is the same with Tangle. We are asked to look at our own rampant population growth as human beings, taking the form of weeds, and the parallel and seemingly unstoppable growth of technology, something else of our own creation.