TU Dance: Accessible Virtuosity

Lightsey Darst describes the surpassingly skillful new company TU Dance in their performance at the the Southern Theater. It's on through June 26.

Beautiful bodies flying in time to music—this is what everyone expects of dance, what the woman on the street will tell you dance is. But the woman on the street does not know how much she will like dance if she views the definition offered in TU Dance’s opening concert. Zippy, lovely, funny, exuberant, and mostly unchallenging, TU Dance (the creation of Uri Sands and Toni Pierce-Sands) is a winner, a popularizer.

If you go to dance concerts looking for avant-garde breakthroughs and artistic risks, if you’ve seen more performances than you can count, if you’re happiest when slightly dislocated, if you quote Derrida at dinner, you may be disappointed by what TU Dance so happily offers. A quarter of an hour goes by without the precious frisson of novelty, conceptual frameworks are minimal or shaky (one piece about high-heeled shoes, another a dreamy salute to stereotypical Southern weather, tea, manners, and hats), and no assumptions are questioned or uncovered.

Before you turn up your nose, though, recognize that every arts community needs frontrunners, groups or individuals who make accessible works that entice new audiences. Without these, the art world can become self-enclosed, niche artists playing to niche artists. Frontrunners make the community more visible and attract money and media support. Remember, too, that since the departure of Danny Buraczewski’s Jazzdance, the local dance community needs a company to fill this role. “Entrance II,” with its effervescent club dancing, society-mint colored shirts and black pants, and techno soundtrack, may remind you of an iPod commercial, but why is that a bad thing? iPod commercials make displays of virtuoso dancing hip. iPod commercials make more people want to dance and see dance, and so will this new company.

Aware of the potential importance of their company, Toni Pierce-Sands and Uri Sands have a two-pronged mission (which they presented in a recent Rake Magazine article by Camille LeFevre). First, the moral purpose: they want to bring together dancers of different backgrounds and, by so doing, integrate audiences as well. Two companies provide inspiration: Alonzo King’s Lines Ballet (San Francisco), and Complexions, Inc (New York). Both try to collect diverse dancers; both attempt to reach cross-cultural audiences.

It’s a laudable ambition. Black dancers rarely appear on Minnesota stages, and judging by TU Dance’s excellent performers, lack of connection, not lack of talent, is to blame. TU Dance also creates pieces about race in America. In “Shapes and Gaits,” two dancers in black-and-white striped costumes, one in black gloves, one in white, curl around each other without being able to touch, while in “Lady,” the mixed cast cavorts happily to the African-inflected music of Ladysmith Black Mambazo.

These uncontroversial, transparent takes on race sometimes feel easy or heavy-handed; I wish TU Dance would trouble the water more, or concentrate on those gray areas already apparent in their opening performance. In “Shapes and Gaits,” for example, three men (two white, one black) alternate playing the odd man out. While one man struggles as if in bondage, the other two pose, sometimes like football referees, sometimes like models. It’s a peculiar mix of sexuality, race, and identity, one choreographer Uri Sands isn’t fully exploring yet. “Tones of Adney,” (named for one of the first integrated lakes in Minnesota) with its flesh-tone costumes, awkward partnering, and oddly peaceful end—two dancers settle from their struggle and watch another dancer upstage, spread out like a water-strider, coming jerkily to life—keeps race as a troubling subtext just under the surface. I wonder, too, whether Sands and Pierce-Sands will take on other racial issues and seek to integrate other dance cultures—Hmong, Hispanic, Native—into their company. I can’t blame TU Dance for not reaching farther yet, though. The points they’re making—that race in America is divisive, and that segregation hurts everyone—may seem obvious, but they still need to be made.

The second part of the TU Dance mission is to maintain excellence in dance. For Sands and Pierce-Sands, this means being perfectly rehearsed and keeping to the physical standards of modern ballet, no matter what the steps. Again, TU Dance seems to look to Lines Ballet and Complexions. The lost ideal of ballet haunts the style of all three: even when dancers flex their feet or pigeon in their legs, their poses, like ballet poses, remain beautiful, even if the beauty is that of a broken vase.

TU Dance’s high standards also insure you will see no slouches on stage. In some other styles, you can dance well without being in top shape, but Sands and Pierce-Sands fill the stage with the most exceptional bodies around, some of them borrowed from Lines and Complexions—geniuses of coordination, freaks of flexibility, attenuated time-travelers and light-speed air slicers. It’s wonderful to see such ability. Sands gives these dancers plenty to do, as this concert is packed with intense dance passages that take primacy over narrative elements. I respect TU Dance for not diluting their work. At the same time, very few steps stand out from the stream; Sands could work on dynamics. Also, because the style uses only certain elements of ballet, movement becomes predictable. Stand on the diagonal with your feet spread apart, one knee bent, one hip cocked, torso erect, arms angular, hands eccentric, and you have a TU Dance move.

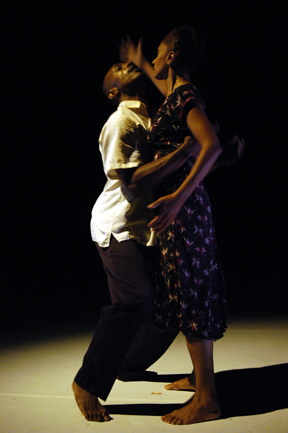

But Sands’s partnering stands out. In “Tones of Adney,” Stephanie Fellner bends and scurries to keep tall, off-balance Peggy Seipp from falling; three dancers climb over each other in complex involutions, one leaving the ground for a moment only to be reabsorbed; Laurel Keen and Alec Donovan wind about each other, giving and taking weight, extending limbs and then curling on themselves like fiddleheads. Here, you might be seeing a Jackson Pollack painting if such a painting could be three-dimensional and created before your eyes, might be watching a camera on a fiber optic cable sliding around the contours of a Henry Moore sculpture if such a sculpture could change like water. See these moments and you’ll find yourself considering the concept of pure dance—an art that can be translated to no other art form, that cannot be described.

It’s difficult to single out dancers in this company—partly because Sands doesn’t give anyone a starring role, and casts change nightly. Out-of-towners Alec Donovan (Complexions) and Laurel Keen (Lines Ballet) might be the most perfect vessels for Sands’s choreography. They have no quirks; neither is distinctive in anything other than physical excellence. Seeing them, it’s hard not to believe their bodies were made for this. Also, Prince Credell (Lines Ballet) shows a rare combination of classical skill, finesse, power, and grace. Local professional dancers remain compelling; Stephanie Fellner in particular finds new energy for this performance. Eva Mohn gives everything away, every moment; sometimes she’s less a body than a sheath of electrical cords rippling with the latest impulse. Finally, there’s long, lean Jerome Barnes, shirt flapping, his body living calligraphy as the lights go out.

The Southern Theater is at 1420 Washington Ave. South, Minneapolis MN 55454; box office: 612-340-1725