Trialogue: Mary Griep and Jantje Visscher at the MIA

Read Michael Fallon's Trialogue (a discussion among critic, artist, and audience) from the Minneapolis Institute of Arts. It's a meditation on criticism, and a personal look at the work of two artists.

Trialogues are the invention of the Visual Arts Critics Union of Minnesota– or “VACUM”– and are discussions among a critic, an artist, and an audience, thus a three-sided dialogue, a Trialogue. Every show in the Minnesota Artists Exhibition Project schedule has a Trialogue; here at MnArtsWeekly we try to publish the transcripts of the critics’ share in them whenever possible. Here’s Michael Fallon’s talk for the Mary Griep / Jantje Visscher shows, “Anastylosis” and “Drawings in Light,” up through August 12.

Preface: Trialogues, Critics, and Egos

I have always thought these Trialogue events offer a rare opportunity, because it’s not often that critics and artists gather together to talk and reveal our relationship in front of an interested public. It’s for this reason that before I discuss the work on display in these exhibitions by Mary Griep and Jantje Visscher, I would like to say a few words about critical practice in relation to art.

There’s a popular notion that critics love excoriation, that they get their kicks by casting artists into oblivion. The recent movie Ratatouille, for instance, portrayed such a critic—whose name, appropriately enough, was Anton Ego. In the movie, this critic serves as an important plot-catalyst when he writes such a mean-spirited restaurant review that the main character’s hero, a chef named Gasteau, is heartbroken and dies. This ends up spurring on said main character—who, implausibly enough, is a rat—to take on the art and craft of his hero and eventually win over the heart of the critic.

If all of this doesn’t drive home the point that critics are mean, the film has Ego write a final musing review: “In many ways, the work of a critic is easy. We risk very little, yet enjoy a position over those who offer up their work and their selves to our judgment. We thrive on negative criticism, which is fun to write and to read. But the bitter truth we critics must face is that, in the grand scheme of things, the average piece of junk is more meaningful than our criticism designating it so.”

As an experienced writer of the occasional negative review on local art, I can tell you that this speech is off-base on several accounts. First off, writing a negative review is not fun, and in fact a critic who writes one risks much—especially in a small art community like ours, where a negative review can, and does sometimes, cause numerous ripple effects of consternation and ostracism.

Further, partially because of these ripple effects and the difficulty of navigating them, but also for various other reasons related to art-world economics, the egos of editors, and the petty jealousies of critical peers, I would also argue that the work of a critic is not “easy.”

Finally, I won’t quibble with the final notion that art is more meaningful than criticism—because of course this is true, much as a baseball game is more important than the umpire making sure it’s played by the rules. But even if art is more meaningful than criticism, this does not mean that critics, like umpires, don’t contribute something to the whole. Just ask any artist who—much like a baseball player pleading a called third strike—has appealed to a critic to write something positive about their art in print.

You’re probably wondering by now where I’m going with all of this. As a critic who’s written nearly 200 reviews, profiles, and critical essays about local art and artists over the past nine years, I’ve thought often about the role of art in society and the role of critics in art. I’ve learned to defend why it is I dislike certain art, why I’m repelled by artistic self-involvement and lack of engagement with the world at large, by overly academic art that is cloistered from the experience of life, by art that’s is self-indulgent or ungenuine or phony.

I’ve also written many pieces describing what it is I like and appreciate in art. All of this writing represents who I am as a critic; that is, there’s a record. Every ballplayer knows that each umpire calls his own unique strike zone. Subjectivity is part and parcel of assessment of every human endeavor. A critic is not a demon nor a walking, talking ego, but a person who writes about art with a particular point of view about it, and nothing more.

The Shows

As for these two shows—“Anastylosis” by Mary Griep and “Drawings in Light” by Jantje Visscher—my particular take is there are things to love about both artist’s works and things that could stand some improvement. Again, these are just my assessments based on what I know and on my own predilections. To start with the positive, I love the way these two artists endeavor to dream through their work, to imagine some imperfect reality and recreate it in a refined or elegant way. If there’s anything I believe, it’s in the power of wishful thinking. Such acts of conjuring through art, of reenvisioning reality, are increasingly necessary.

We need art that assumes that human endeavor can cause meaningful and abidingly positive change. This is not a popular notion in an era when the US government irrationally justifies torture, excuses illegal actions by cabinet members, ignores the mounting evidence that we are causing our global climate to warm, and uses science not as a means to solve human problems but as a tool to gain political points.

Perhaps this cognitive dissonance explains why so much of contemporary art does not pursue the idea that art can help realize better things. This wasn’t always the case. Artists like da Vinci, Brunelleschi, and Michelangelo were men of reason who pursued science, engineering, and architecture hand-in-hand with their art—in pursuit of the idea that humans had the capacity to reach for perfection or to marshal their resources for the betterment of life. For whatever reason, artists seem to have lost this notion. We seem to feel that artists should draw primarily from expressive and intuitive parts of the brain, to explore the self and not be concerned for the exterior world.

I think this leads to an unhealthy notion—a right-brain, left-brain disconnect that divorces rationalism from art and magic from science. I once wrote these words on this subject:

We moderns know how to research and create elaborate theoretical psychic raincoats, but we generally lack an ability to see the wonders of the world. Ancient cultures appreciated [these], and made up stories about them so that they could understand and hold onto them . . . For instance, the Mayans carefully recorded the changing arc that the sun inscribed in the sky throughout the year, forming accurate calendars . . . ; ancient Native American thinkers also observed that the sun “had the power to grow crops,” a notion that Enlightenment-era New Worlders scoffed at. While modern science has produced wonders of technology and imagination, I often wonder if we are any better off for our ability to explain the facts of the universe and not the magic and beauty of it.

The good news is you can still find artists and scientists who understand the value of combining the two sides of human thinking, who know there is magic in what is seen, and there is reason in what is unknown and dreamt about.

Consider Mary Griep’s work. It begins with wishfulness from the very beginning—its title, “Anastylosis,” is a reconstruction technique in which a ruined archeological monument is restored after careful study by using original architectural elements whenever possible, as well as supposition and guesswork when necessary. Detractors of the left-brained scientific sort see problems with this—no matter how rigorous the study, errors in reconstruction are inevitable and original components will be damaged.

But I like the idea of analstylosis—the wishful thinking, the inevitability of mistakes, and the glorious and beautiful hubris of the attempt to reimagine and recreate—if only because it’s the only way we can even begin to realize unknowable mysteries. I like historical novels for this reason—that humans have the capacity to wonder and wander through past epochs, to travel through the time-space continuum just by virtue of our cranial capacity.

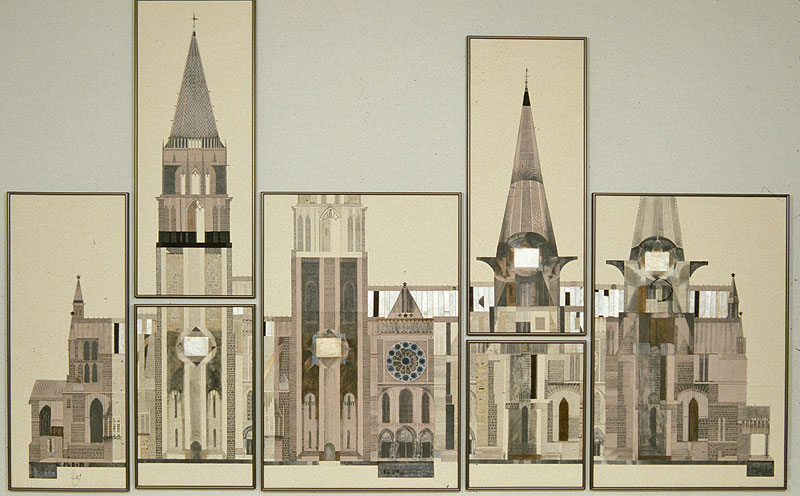

In Griep’s work, this wishfulness reveals itself in the impossible and highly obsessive-compulsive charting—brick by brick, cornice by cornice, mosaic tile by mosaic tile–of one version of the ruined sacred spaces, temples, cathedrals, and other monuments of the past. The finished works, inevitably flawed, proudly wrong, full of absolute humanness, are gloriously beautiful for the imperfection inherent in their execution. They are charts of futility—mapping through guesswork and supposition an entire world of possibility that simply cannot be known but we can’t help but wonder about.

These are like the maps made in the late 1400s, after Columbus returned to Europe and rocked the collective understanding of the world’s layout. In some maps, for example, Florida is in a strange place in relation to Honduras—right at its shores, actually–and up until about 1540 mapmakers imagined a place they called Arabia Felix. Griep’s images are like Arabia Felix. There is something immensely poignant about such human mistakes. I love that Griep’s works, like maps in 1500, have the outward appearance of logic and perfection, wrong as they are. I love that up close the logic and sense of perfection in Griep’s images fall apart to reveal patchy, scratchy, uncertain lines, collaged elements, and mishmashy imagery, willingly reflecting their imperfection.

As for what concerns me about these works, there is a current term in vogue in the art world for what Griep is undertaking in these works–“deep investigations.” This is another attempt to say that now, in the po-mo condition, we are all becoming our own art movements, and instead of artists latching onto –isms, they are, partially as a marketing tool, more and more applying skills and attention to deeper looks at certain eccentric objects or notions or systems previously unexamined in such a deeply detailed way. Andreas Gursky’s photographs, for example, of candy stores with rampantly colorful and overflowing aisles, or of stock exchanges flooded at peak hour with every imaginable stock of humanity are so heavily detailed as to be overwhelming, devoid of human emotion. Fred Tomaselli, whose collages of pills, leaves, butterflies, are explosions of colors and shapes that threaten to overwhelm the senses and befuddle the eyes, is another good example of this. In fact, the list of artists dealing with visual overload and obsessive accretion is long—Julie Mehretu, Daniel Zeller, Lisa Corinne Davis, Thomas Struth, and so on. These artists often refer to so-called “systems” that they attempt to harness and tame for purposes of composing their sometimes joyless visual overload. Call it obsessive-compulsivism if you will, a minor movement commenting, with completely blunted affect, on the overwhelming visual nature of our world. I find such work interesting and compelling on the front of the tongue and perhaps longer, but the aftertaste of such work I find just a tad soul-unsatisfyingly bitter.

This wish to capture and control and conjure seemingly impossible visual material through obsessive investigation is what connects Griep’s work to Jantje Visscher’s in the next room, and is perhaps why panelists saw fit to conjoin her work with Griep’s. Visscher’s works are forms of clear plastic pinned to the wall that, making use of the refractive properties of the plastic, cast a variety of shapes, lines, and subtle colors on the surface of the wall beneath. That the colors and refracted light are as crucial a part of the work as the unremarkable pieces of plastic that create them is key.

In the gallery guide, Visscher explains that there is no word in ordinary English for the type of refraction she conjures from her plastic objects. She seems to suggest that her work is a kind of speaking-in-tongues.

Her work conjures up visions that are impossible to conjure, like a snapshot moment of a waterfall or a wave form or a microscopic snapshot of the fractals of ice crystals forming, or the frozen moment of a lightning strike against an object. In this way these are constructions every bit as wishful as Griep’s.

The interplay of Visscher’s items with the ambient light and with strategically placed light fixtures creates swirling patterns of shadows and luminous droplets that are rapturous and enjoyable, but they are all the more so because they are seemingly impossible. The lines of shadows and refraction seem more real than the plastic objects that create them. They seem to have shape and presence, but if you turned the lights off they would disappear. The works conjure colors out of thin air and harness the air around them to create form. And finally, when viewed up close, the plastic, replete with clumsy marks and awkward creases that create the light shapes and shadows, reveals, like Griep’s work, how human imperfection brings about the beauty of this art.

The only quibble I have with these is, as with Griep’s work, they seem to lack an emotional component. They seem too concerned about scientific principles to ever fully capture my heart. This is a minor quibble, and I’m not sure I fully understand why I am reacting this way, but nevertheless I wish for more human warmth in them.

In the end, I truly love art that makes something out of nothing, that posits a truth different from what is known, that takes presuppositions and turns them on their ear, and that thumbs its nose at the conventional wisdom. I like art like this that challenges my world view and reveals to me something I didn’t know about the nature of reality. I only wish there was more such in our stuck-in-a-rut and increasingly wonderless world.