To Learn By Rote and Remember By Heart

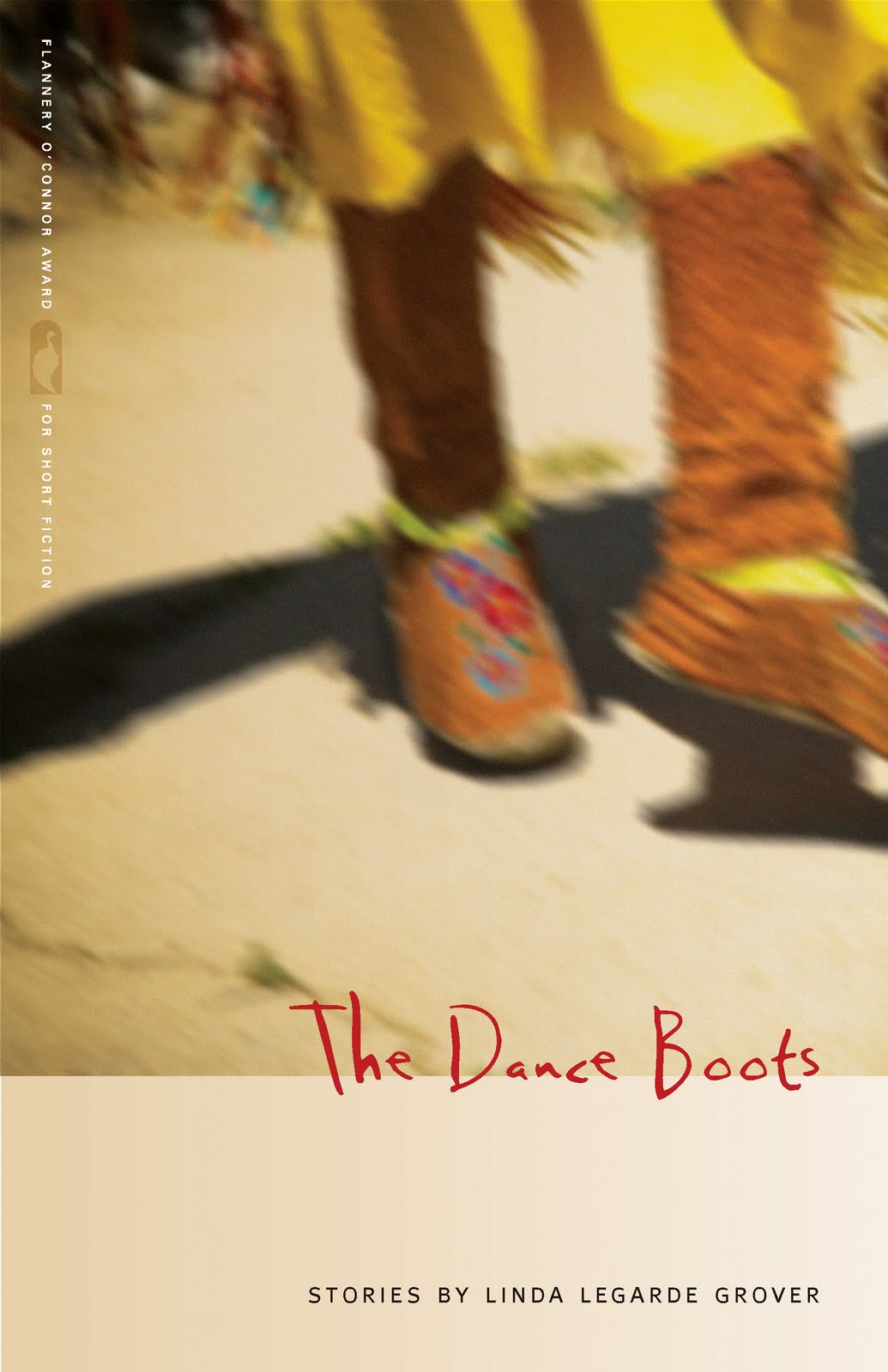

Poet Connie Wanek reviews a new story collection by Duluth-based author Linda LeGarde Grover, THE DANCE BOOTS, which recently earned her the Flannery O'Connor Award for short fiction.

AFTER I READ THE FINAL WORD (“HOME”) OF THE DANCE BOOTS, Linda LeGarde Grover’s new collection of stories, I turned back to the first words (“We Ojibwe believe”) and began again. I wanted to extend my stay in the world the book creates. It’s a compelling place of tradition, generosity, endurance, painful memories and events, spiritual transcendence, love and humor. LeGarde Grover won the prestigious Flannery O’Connor Award in short fiction for this book, and I can’t imagine a more worthy recipient.

The eight linked stories that comprise The Dance Boots can be read individually, each on its own. But characters who will be important in later stories are introduced in the first tale, as Aunt Shirley passes the family stories down to her niece, Artense, in accordance with Ojibwe oral tradition. The physical emblem — the symbol, if you will — of this cultural and familial inheritance is a pair of boots that Shirley herself wore to Powwow dances, and which she gives to Artense to wear: “When I picked them up, the touch of suede against my fingers was oily and cool, and I shivered, but back in the living room I held them to my heart like a baby and said, ‘They fit perfect. Miigwech.'”

I found the frequent use of Ojibwe words and speech patterns, as here, especially interesting. Most of the terms are either explained, or their meaning can be gleaned from context; but some are simply allowed to stand, mysterious, an assertion of linguistic integrity that I liked very much. I also loved the texture of the prose and the wonderful details. Some passages are reminiscent of Faulkner, in part because an Ojibwe world is created in these stories, similar to Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha County — less a geographical place than a spiritual, cultural, and ancestral home. Also, some scenes have a subjective, meditative, Faulknerian, run-on quality as the author probes into memory and emotion; each layer she passes through creates a shimmering depth.

Here is an extended paragraph from the story “Maggie and Louis, 1914.” The setting is the laundry room at an Indian school, where Ojibwe girls are sitting at a work table learning to darn socks:

Breathing. Some girls breathed lightly, some heavily, though their mouths, concentrating both to obey the matron and to please the new helper, an Indian girl dressed like a white lady, like a teacher. After a while, warm breath, curling ribbons of air, gently waved and wound through the room, twining air tendrils around the girls, around Maggie and the matron, around the work table and chairs, the baskets of mending, the ironing table, the gaslight that hung from the center of the ceiling on a heavy chain. The room became dreamlike, the seamstresses sleepy. Someone’s nose whistled softly and plaintively, reminding Maggie of the cries of ducklings swimming behind their mothers at the shore of Lost Lake in late summer, paddling strenuously with infant webbed feet, straining to keep up. ‘Don’t leave me behind, don’t leave me behind,’ their tiny weeping coos begged pitifully. Warm late-summer air wound and curled over the lake, twining damp tendrils around the ducklings and their mother, around Maggie and the rushes that grew higher than her shoulders, around the pale green frieze of ripening wild rice near Muk-kwe-mud Landing, across the lake. Maggie leaned into a crescent of air that supported her as she bent forward from the waist to scoop up and cradle in her hands the last duckling, the smallest and slowest, the one forgotten by its mother and left behind, the duckling that was really a darning egg inside a crumpled long black stocking, and stroked its downy back.

The girls’ breathing becomes the warm wind across the lake, and the “twining” movement of both of these is like the girls’ darning, the threads weaving over and under each other. The darning egg becomes the duckling. The cries of the ducklings as they fall behind capture the lonely homesickness of the girls, forced to leave their mothers at such a young age to live at the Indian school. These kinds of correspondences, this kind of thematic and metaphoric richness, is a quality we usually associate with poetry.

______________________________________________________

I did not find a false note or a facile moment in her new collection of stories. Nothing is sensational, merely for effect. In fact, the kind of this kind of thematic and metaphoric richness in these stories is a quality we usually associate with poetry.

______________________________________________________

LeGarde Grover, in fact, released a poetry chapbook in 2008 called The.Indian.at.Indian.School. It was published by the University of Arkansas at Little Rock, and it’s currently available in full online here. If you do follow the link, you’ll find a remarkable photograph, the cover image of the chapbook, an image that haunts both her poems and the stories of The Dance Boots. And, of course, there you can read her wonderful poems.

I did not find a false note or a facile moment in her new collection of stories. Nothing is sensational, merely for effect. The story, “Shonnud’s Girl,” for example, set in 1936, follows an Ojibwe family, husband, wife, and three children, who fall on hard times in the Depression. The father finds work helping a farmer, and they live in the original, two-room homesteader’s cabin still standing in a field on the property. The children are eventually left orphans, when the mother abandons them and the father dies of stomach cancer, and it’s hard to think that there would be any room for joy, or even ambiguity, in such a story. But there is: a trip to the dump, to see what good and useful things might be found there, to socialize and have a simple picnic, to just spend a day with a beloved mother — this is one such joyful memory, as are remembrances of innocently “stolen” rides the sisters took on the farm horses in the nearby pasture.

Despite one sadness after another, Shonnud’s girl, Rose, who narrates the story, concludes her tale of separations and losses by saying, “See, for me, what I have learned is that we have a place where we belong, no matter where we are, that is as invisible as the air and more real than the ground we walk on. It’s where we live, here or aandakii … Any of us by ourselves, we’re just one little piece of the big picture, and that picture is home.”

I marked passage after passage as I read — this one for the humor, this one for the luminous description, another because it illustrates a particularly keen psychological insight. Rose, for example, wonders at one point what her life might have been like if “Violet and I had gone away to the Tomah Indian school.” She wonders, given the sad chaos that marked her childhood, “how it would be to live in a dormitory, have your own bed and a little trunk to keep your letters and things in. To sleep between sheets, to wear clean clothes all washed and ironed, to line up in the lunchroom to get your meals on a tray, at exact times of the day. To know just where to go every minute, and just what to do.”

This haunting passage is not a recommendation for Indian school! It shows, rather, how deep her grief was and is; it’s a very brave thing to think and say, and a sad thing to wonder. We’re certain by the end of this book, if we didn’t know already, that sending young children away to Indian school was “a vast experiment in the breaking of a culture through the education of its young.” Rose’s survival and her sense of reconciliation and even peace, came at last at home on the Mozhay Point Indian Reservation, a fictional allotment lands north of the real town of Duluth.

In some ways The Dance Boots reads like a novel, one that moves back and forward in time. Many characters appear and reappear from one story to the next, at different ages and in different circumstances. I’m glad the book starts where it does, though, in the company of Aunt Shirley and Artense, with humor and gossip, and in the generous and kindly atmosphere of women in the dressing room preparing to dance in a Powwow. There are plenty of heart-breaking moments ahead. The book ends well, too, on Bingo night, when even to lose, or to be lost, is lucky.

______________________________________________________

Related events:

Linda LeGarde Grover’s new collection of stories, The Dance Boots, will be released from University of Georgia Press and available at bookstores beginning September 15.

Upcoming author readings in Minnesota include:

- A book release reading and celebration at Birchbark Books & Native Arts and Kenwood Cafe in Minneapolis, September 17 at 7 pm

- A publication party for the author at Northern Lights Books and Gifts in Duluth, September 23 at 7 pm.

______________________________________________________

About the author: Connie Wanek is the author, most recently, of On Speaking Terms (Copper Canyon Press, 2010). Her work has appeared in Poetry, The Atlantic Monthly, The Virginia Quarterly Review, Narrative, Poetry East, and many other publications and anthologies. She has been awarded several prizes, including the Jane Kenyon Poetry Prize and the Willow Poetry Prize, and she was named the 2009 George Morrison Artist of the Year. Poet Laureate Ted Kooser named her a 2006 Witter Bynner Fellow of the Library of Congress. Her poem, “Polygamy,” was the grand prize winner in the 2010 What Light competition.