Thinking Souls: Real Karaoke People

Read on for Shannon Gibney's review of Ed Bok Lee's "Real Karaoke People," and go to Thinking Souls Read, our online book club, to discuss.

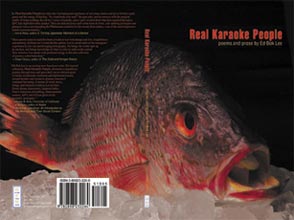

Delinquents. Street-walkers. Brothers. Men who’ve traveled halfway across the world just to work in a seedy grill somewhere in Colorado. These are the people and the voices that fill Ed Bok Lee’s Real Karaoke People (New Rivers Press, 2005), and the stories that stay with you long after you’ve put the book down.

If there’s one thing Lee’s got a hold of, it’s the sound and timbre – even the resonance– of the way things are told. He’s concerned with the what of every story, of course, but the how feels more like it’s at the center of these dirty and difficult serenades.

Take the poem “Frozen in the Sky” for instance: “…I saved your people, says the old man. / A toothless wad of day-old sugartwist / on his tongue. Curdled body / of the second coming, or muffled / lament of a dozen gook legs and bellies / choking the rice paddies / in Saigon. No Gun Ri. / Iwo Jima. Bataan.” Reading these lines, we feel as if we’re standing beside the old Korean War Vet in front of the Sunrise Donut Shop, shivering with the narrator. It’s not just a poem about an old, homeless white man who is trying to connect to someone who happens to look like the people in the place where he fought in a war. No, “Frozen in the Sky” is also about how language ties us to each other in the most devastating ways, and about how it always carries the weight of both personal and collective history.

If this history is not pleasant, at least, Lee points out, it is sometimes funny. We see this in pieces like “Skip Ching Porn King:” “My name is Skip Ching and I’m what you might call a porn / king. You may have seen my latest video – Skip Ching’s Gang / Bang Rides Again, recently remastered on DVD. In it, I play an / Oriental railroad worker turned cowhand, named… / …Skip Ching.” Skip Ching uses the rest of the piece to refute various “harmful stereotypes” we may have about the porn industry. Underneath this “expose” is a complex layering and critique of the very real stereotypes of Asian masculinity (and therein lies the humor).

Parts of Real Karaoke People also cut you unexpectedly, as in “The Secret to Life in America”:

“My brother sits me down and tells me

the secret to life in America.

I’m twelve years old when this happens.

He grabs my shoulders and says:

No one likes an immigrant.

It reminds them of when they fell down

and no one was around to help them.

When they couldn’t talk.

As children when they got lost in public.

Cold and wet, everyone hates an immigrant.

So don’t trust nobody.

The Whites, they’ll teach you

to hate yourself for being silent.

They’ll punish you for fighting back.

They’ll love the taste of your food and culture, and sister…

and yet spit you out.

The Blacks, at first you’d think they understand loss.

But to them you’re just another cracker with a bad case of

jaundice.

Don’t expect shit from them,

they can’t afford to be generous.

Latins laugh behind your back.

Do you know this? I’m trying to tell you

how it is in the city,

he says.”

This critique of the hierarchy of racism in America is beautiful in its lucidity, and breathtakingly painful for its truth. Although some people have more power than others, there is always the power of other-ing, of skin tone, of native tongue, or hair, or anything that can divide one body from another. And in this country, as the brother’s voice conveys in fevered pitch, there is almost a rabid hunger to enforce and reinforce these divisions. Either accept this rule, or die by it – this is the secret to life in America.

But Real Karaoke People also allows inanimate objects, not just people, to tell their stories. “A stone from my mother’s garden sits by the sink, / solitary as the sunlight / she rinsed it in. // Two pounds to hold down / napa cabbage, garlic and red pepper / in brine. A humid eight-day foment /stuffed into a gallon-sized glass. Sprinkles / of ground anchovies to nourish the spirit / tiny-gurgling up like a lunged life / through the kimchi’s orange blood,” (“Kimchi”). In this way, Lee is not hemmed in by narrow definitions of voice. He finds voice in everything – even in the spiritual, the indescribable.

This very open approach to voice, coupled with the book’s subject matter may be why Real Karaoke People feels so epic. Lee mixes the rawness of South Minneapolis street life with the brutal imaginings of parents and grandparents living through the Korean war, sometimes all in one stanza. Reading these poems and prose, you feel as if the history of an entire generation, of the children of Korean immigrants, is pouring out in front of your eyes, which is why, as Lee says in the poem “That Smell,” “…it cuts to the bone; / part fire, water, air and soil; / not canned flowers / or the suburbs, // but a monk winged with flames for his principles; / napalm, Agent Orange and severed tongues; / cash money smudged with blood, oil, / smart bombs, nerve gas and radioactive pus… // incense of prayer on my father’s fingers.”

Next month: Get into summer reading with Peter Brown’s novel The Fugitive Wife (Norton, 2006).