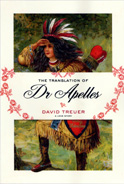

Thinking Souls: Book Review: The Translation of Dr Appelles

Shannon Gibney opens David Treuer's new novel, "The Translation of Dr Appelles." She finds it marvelous--and invites you to discuss this book in Thinking Souls Read: our online book club.

If you are one of the many millions who couldn’t get enough of The Usual Suspects, David Treuer’s third novel,The Translation of Dr Apelles (Graywolf, 2006) will similarly delight. Although this may seem at first to be an odd, if not unlikely comparison, the two stories’ finales, in which the assumption of “the true story” is completely turned on its head, and therefore everything that has come before must be reevaluated, are remarkably aligned.

Make no mistake – Treuer’s book is much more than a mystery. It is first and foremost a love story, though not of the usual kind. The Translation of Dr Apelles is a romantic encounter with language, a meandering and deeply-felt exploration of the body of, as Treuer writers, “a vast and wonderful library.”

The book opens as Dr Apelles, a middle-aged bachelor and a preeminent translator of Native American languages, begins work on a document that only he can decipher. “…finding the document makes him realize that he has never been in love. Suffice it to say, when he first found the document, his world, as it was, collapsed. And he relives, each and every day, the feeling of that discovery.” After the full weight of this realization has sunk in, Dr Apelles sets out to fall in love – a quest which turns his whole orderly and controlled world, upside down.

Treuer writes, “It is one thing to translate a thing, and something else completely to have that thing read. It is one thing to love someone, and something else entirely to be loved in return.” In this way, the academic act of translation, and the intellectual and imaginative act of reading, become a metaphor for the emotional act of falling in love. If this connection, at times, feels a bit overdetermined, if we feel the narrative hand of the writer steering us toward his own conclusions a bit too forcibly, we can forgive him for the precision of the prose, the relentless attention to detail. Passages like the one below allow the reader to enter the marvelous and banal world of Dr Apelles and his translation, to really struggle with him as he navigates the safety of his structured life, and the delicious abyss of romantic love.

“They were too much on edge, too much subject to the wonder and strangeness of it all. They were startled by he very fact of riding in a cab together.

After a series of twists and turns on the small side streets they turned on the main thoroughfare, which was – unbeknownst to Campaspe but knownst to Dr Apelles – the old post road that led into the city. The road followed the canal for a distance, and all that could be seen were the outermost branches of trees that had worn the blossoms of spring only hours before, but which had now been transformed into icy, clawing things, fairy-tale trees. The small saplings planted on the greenway were bent low under their armor of ice. Here and there in low areas fog curled on the ground and seemed to hide mysterious secrets that excited Dr Apelles and Campaspe,” (pg. 135).

As is common in the romance genre, the prose sometimes becomes enamored with itself, becoming almost florid. But this excess occurs in the service of a less visible central character – the odd and opinionated narrator himself – and often results in unrestrained moments of beauty: “Now, if Zola, or anyone else, but if Zola at the restaurant had asked what was it like when you were growing up? what was the reservation like? could he say that the days, the short days of winter and the long days of summer, when the sun stayed so long that just when the afternoon began it felt like a whole new day had been added on to the one you had just enjoyed and the night would never come, and that in these hours life was very full, and there was so much to do you never wondered who you were and what the answer might mean, and that the people of your childhood, your parents who, neither one no matter what, ever said or did a cruel thing, and your uncle often got very drunk but was always kind, and Adolphe who lived behind the village had such a funny way of swinging his arms when he walked and he walked with a limp because he had dropped a crate of ammunition on his foot during the First World War but played the fiddle at all the jigs, or the girl who owned a pack of dogs and could climb trees like no one else ever could and who climbed those trees and kept those dogs and sicced them every so often on her own father when he met her in the woods when she was alone because he wanted things she did not want to give, or the land itself; the ever-stretching swamps into which it felt that no one had ever gone before you and the pinestands, those that were left, anonymous and communal, and the hardwoods so full of secrets but so quiet and good to hunt in if there was no snow. He could not,” (pp. 200-201).

The overarching questions about the relationship of identity to language, of what is gained and lost in the process of translation, of the power of story – although all of these questions at times feel a bit too orchestrated in The Translation of Dr Apelles – they also resonate deeply on many levels, and probe the reader to interrogate her own assumptions about “Indian-ness” and intimacy. “But his life was real to him, and if he told it in the wrong way or for the wrong reasons it would cease to be real, it would no longer be his life because it would become a story like all the other stories about his people, and if he told it he would only become a character in that story and would be only the Indian they knew and the Indian they told their friends about. His life would cease to be his and he would not even recognize himself anymore,” (p. 203). Such are the stakes of the linguistic enterprise, as well as self-expression, both of which have not really been explored in the Native American context in fiction in this way before.

In fact, The Translation of Dr Apelles offers readers so many avenues of entry – as a meditation on language, as a exploration of story structure, as a “double” romance, as a mystery – that it just may be one of those rare books that has something for everyone. Who, after all, couldn’t enjoy a novel that describes the very process that the reader is engaged in so sensuously? “He reads with his hands and his eyes – the arch of her neck, the sweat that shines on her temples, the small movements of her fingers as they steady the turf of his chest, the dark heat of her groin, and her thighs too, and all of her. And a story it is to read. What a pleasure. Page after page after page.” (p. 149).

Don’t miss your chance to add your voice to the mix – the Thinking Souls online book club is the place to hash out both formed and incipient ideas about art and writing in Minnesota!

Next month: We’ll talk to Arleta Little of the Givens Foundation for African American Literature about their work promoting and preserving Black literature. Pick up a copy of Harriet Jacob’s Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, an American classic and a Givens Foundation re-issue, for September book club dis

David Treuer reads from his new books, The Translation of Dr. Apelles and Native American Fiction: A User’s Manual (both Graywolf) at 7 pm Wednesday September 13 at the University Bookstore in Coffman Memorial Union.