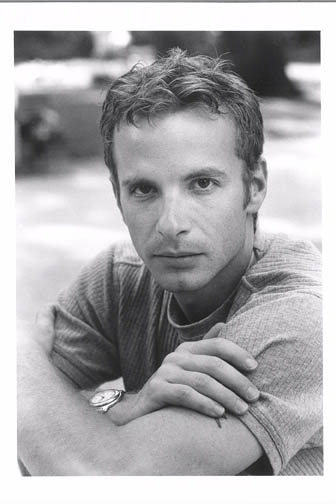

Thinking Souls: An Interview with David Treuer

Shannon Gibney speaks with David Treuer about his two new books: a novel, "The Translation of Dr. Appelles," and a book of essays, "Native American Fiction: A User's Manual." These will be important books in more than one tradition; read on!

IntroductionDavid Treuer’s two new books, The Translation of Dr. Apelles and Native American Fiction: A User’s Manual, are being released by Graywolf this month. Native American Fiction, a collection of critical essays on Native American literature, is raising quite a few eyebrows, and even getting some people downright angry. Here, Treuer discusses what the fuss is all about, and why literature must have its own culture, aside and apart from material, lived culture.

Shannon GibneyI found Native American Fiction very provocative and interesting.

David TreuerYeah, it’s probably going to be quite provocative.

SGCan you talk about this phrase, in the beginning of the book: “…it is death that gives fictional Indians their power. Death grants them a knowing essence,” (pg. 16).

dtIt’s a pet theory. And we’re talking about books, not about life, although there’s some bleed-over. One of the most persistent myths about us is that we’re dead.

My brother and I went to college together; we were both there at the same time. They used to call us Night and Dave growing up, because I looked like Opie Taylor, and my brother looks like a “real” Indian, dark skin, long dark hair, braids, whatever. So that was really flattering.

So you know, there is the usual college question: You meet someone who is ethnically vague, as far as most of us are concerned, and ask, “Well, what are you?” And so I said, “Well, we’re Native and Armenian.” And someone said, “No, you’re not.” And I said, “I just told you what I am, what do you mean?” And they said, “Well, they’re all dead.” And then, on a different occasion, someone said, “Oh, it’s terrible what they did to you.” And I said, “What do you mean?” And they said, “Well, they killed you all.” This person was completely unaware of the irony of claiming that someone who’s standing right of you is dead. So there’s that in life.

And in books, Indians and in culture kind of, this is true for books that are non-Native, but also largely true of books written by a lot of Native writers, Indians and Indian culture, which are somewhat interchangeable in fiction, kind of work the same way that ghosts work in ghost stories. They can’t affect any kind of real change, because they’re ghosts. So that’s more or less what I meant in that statement.

sgI was also interested in that distinction that you’re making. It seems like you want to talk about style.

dtYes.

sgAnd you are less interested in border-policing, in terms of this issue that you discuss on page 5, “I am concerned with echo, not origin.” And then you go on to say that, “It is crucial to make a distinction between reading books as culture and seeing books as capable of suggesting culture.”

dtRight.

sgCan you talk about that? You’re getting at a lot of subtleties here, so I’m wondering if you could clarify them.

dtWell, you’re probably familiar with this, too. Beginning with multiculturalism in the late -‘1980s, early ‘90s, there’s this increased attention being paid to African American writers, to Native American writers, Asian American writers, etc. These books found their way into curricula, but largely as cultural pieces.

And so, I don’t know if you ever heard this silly response on the parts of some readers, reading something about African American culture or Native American culture, saying, “Well, now I know what’s like to be Indian. And now I know what that life is like – I had no idea.” So they think that the book itself is the culture, that they’ve somehow interacted with the culture. And maybe it’s my anthropological training, or maybe it’s just… I mean, culture is sort of a living, breathing organism that’s always in flux and is always changing. It’s transmitted between people, it occurs between people. The thing is that books aren’t alive, in the general sense.

I mean, a lot of Native writers will even say, “Well, I’m not an expert. I don’t mean this to be some sort of cultural artifact.” But nevertheless, they are taken this way. They are taken as manifestations of some sort of cultural sensibility. Which is so weird, especially in the Native context, because most Native writers that I know of don’t speak any languages. If they were writing their books in Ojibwe or Cree or Navajo or whatever, then that would be something different. You could make the argument that those texts could be seen as cultural artifacts. But these are books written in English, by people whose first language is, by and large, English. And so the claim of the sort of “cultural truth” in them is really problematic.

sgIt’s almost like this brokering of cultural capital.

dtWell, it’s this cultural industry, which kind of rose during the rise of multiculturalism, in the ‘80s and ‘90s. They were marketed and sold, largely promoted. And sometimes the writers supported those endeavors, sometimes they didn’t. But they were marketed, sold, promoted as cultural items.

It’s more pronounced in the Native context than it is in other contexts, I think.

I really engaged with questions of origin in graduate school, and then I just got really frustrated. So then I just said, “Okay, it’s really hard to say where it started. So let’s just look at how it acts. Let’s see what we come up with.”

sgSome of the arguments you’re making here… I think there’s a worry here, especially among communities of color that have experienced so much appropriation of our artistic production, cultural production, literary production, etc. that when you locate culture within a body – a Native body, or an African American body, for example – there’s at least this illusion that you can control some of that appropriation a little bit.

And it seems that what you’re saying, if I’m reading you correctly, is this: It’s a question of style. Anyone could write “a Native American novel,” – a White person, or anyone. Am I getting you correctly?

dtKind of. I think part of the problem is that all along, all writers – whether White, Black or Native – appropriate. And Native American writers often act like or are described as though they’re not. But that they’re somehow channeling some kind of tribal knowledge.

But Sherman Alexie is channeling Forrest Carter, whether he knows it or not. And James Welch is channeling is Cooper and Homer, whether he knows it or not. And these aren’t criticisms; I love how everyone always does that.

Sherman gets really incensed by these Native imposters, these people who sort of pass themselves off as Native writers writing Native books. And that sort of thing pisses everybody off – it pisses me off, too. But that’s the risk we run if we persist in acting as though there’s some sort of identifiably, resolutely, fundamentally Ojibwe book.

Because anybody can write anything to sound like anything. So if we look at culture as text, then we open ourselves up to appropriation. We leave ourselves vulnerable to it. And that’s a problem.

So, yeah, I’m concerned with that. But the point of the book is not that it doesn’t matter who’s writing it. It does matter. As Toni Morrison put it to me when I was her student, “When someone who’s not Black is writing a book with Black characters, using Black idioms, they have a different responsibility to their material than I do. And they can probably get away with more than I could do in good faith.” And so, it’s that sort of “in good faith” which is really important.

There are certain ways of imagining Indians which I can’t bring myself in good faith to do, without feeling like I’m violating myself, or my family, or my reservation, my community, not to mention my race. But largely, that’s part of the problem, that race and culture are conflated; they’re interchangeable now. And I don’t think that they are interchangeable.

sgIs that part of what you want this book to do?

dtYeah. I want this book to help people read Native American literature as literature. As documents made up of words dropped from the personal imagination and the influence of words around them. As constructed, imagined documents. That’s what I want people to read our stuff as.

Because unless we’re able to do that, the books don’t get evaluated as books. They get evaluated on whether they’re culturally “true” or “authentic.” And what passes as “authentic, Indian literature” is getting narrower and narrower and narrower. It’s harder and harder to write. It’s harder and harder to read in a way that’s enjoyable.

And if Sherman and Leslie Silko are right, in that these works are somehow Indian, and that their truth is what makes them important, they should just write ethnography. I mean, why not? But then, we all know that that’s somehow wrong, or somehow wouldn’t be satisfying, so what then is it about imagined works that is so satisfying?

They’re fantasies, they’re fairytales that seduce us, but they’re not true. And they shouldn’t be judged on their truth value, they should be judged on their literary value. And frankly, a lot of Native American fiction is really bad.

sg[Laughing] But you know what? You get crucified if you even bring stuff like this up in your own community. In the Black community, I find this to be true. Artists of color, because we live in this larger mainstream culture, which is so derogatory in so many ways, and so devalues our artistic production, they get into this place where, as an artist or critic (as you rightly point out, most artists are critics, and need to be critics to produce good works), we’re you’re seen as a traitor —

dt…if you critique.

sgRight.

dtWell, that’s just wrong. Critique makes our work stronger. Honest critique… I mean, I talk about a lot of people in there who I think are friends. And I say a lot of things in there which I think are true, and good. And then I raise some really hard questions, which I think are true and difficult.

No one who has seen the book so far has said, “Your conclusions are wrong.”

sgReally?

dtNobody has argued with me on the basis of what I’m saying. But they have said, “How could you do it?”

sgWhat does that mean?

dtWhat you think? They’re saying, “How could you talk about this stuff in public? How could you say anything negative, or that could be construed as negative?”

But without that kind of honest, friendly discussion about what we make, and also what stands behind it, we’re really going to kill what strides we’ve made in the past 30 years in our work.

Native American fiction was made in many ways with N. Scott Momaday’s House Made of Dawn, which was published in 1968. And people like Momaday and Louise Erdrich and Leslie Silko and a few others basically made our genre from scratch. They put it on the map. And it’s never really been taken much further than what they’ve done. It’s regressive these days – the genre. It’s not getting bigger, it’s getting smaller.

sgCan you specify what characteristics you define as regressive?

dtLiterature as cultural wish-fulfillment. Literature whose largest themes are recovery and rediscovery. So you have these books that are just basically a desire for culture. And you have – and Sherman’s most guilty of this – a kind of anxiety about racial mixing. Have you read Reservation Blues?

sgYes.

dtDid you pick up on this anxiety over racial mixing that saturates his entire book?

sgYeah, but I feel like a lot of his work has that.

dtWell, yeah. You know, he talks and says, “Well, I’m 13/16ths Spokane Coeur d’Alene.” And I’m like “That’s really great. I don’t really care about your blood quantum.” Nor do I care about it in terms of my life

Meanwhile, this erstwhile Navajo guy, who really wasn’t Navajo at all, wrote these two bestselling autobiographies, which weren’t at all true. And Sherman just excoriates them. I was like, “What’s really interesting is that you pretended to be Navajo in order to write this book. The version of Indian life that he presents – the kinds of Indians, the kinds of experiences, not to mention the literary style – where does it all come from? He must have invented it, because he didn’t live it. Well, he exactly mimicked Sherman: His kinds of characters, his kinds of reservation settings. I mean, just in terms of where people live, and how their houses look, and what kinds of things people say to how they experience the world. It’s drawn from Sherman.” So I just find that highly ironic.

This is largely what The Translation of Dr. Apelles is about. It’s about this Native character, he just got a Ph.D., he works in this east coast library. He’s a bachelor, he doesn’t have any kids. He’s not estranged, but just distanced from his family. He’s fluent in about seven or eight different languages. And yet, according to the rules of authenticity, he doesn’t really count, in terms of how we think of the typical Indian being: he doesn’t live on a reservation; or drive this old-beat up car; he doesn’t do quirky things, like drive his car backwards; he doesn’t talk about coyotes; and he’s not poor.

And so, at the beginning of the book, he discovers a manuscript that only he can translate. And then, he also realizes that he’s never been in love. So he sets out on this quest; he says, “I’m going to fall in love.” That’s his goal. It’s a silly goal.

But part of his dilemma is that he feels like he’s got no language for himself, in that how he feels he really is, he can’t communicate. So translation is a metaphor for love. How do you translate your inner-self into a language that someone else outside of you can understand, and nothing’s lost in translation?

And it’s also a metaphor for culture. He falls outside of what people take as an “authentic Indian,” so he’s got no way to express himself. He hasn’t communicated this to anybody, and it’s painful for him.

We could talk about my life, and no one would recognize it as being essentially Indian, but it is to me. I’m Native. I was born and raised and grew up on my reservation, speaking my native language. I was involved in my traditions. My brother is the most preeminent translator of Ojibwe texts. I feel central at Leech Lake, and very comfortable, and that’s where I’m from. And I also went to summer camp. And I didn’t grow up poor. Life wasn’t a mean struggle. I’ve fought for what I have, and I’ve worked for it, but I always had food and clothing and a roof over my head. I had parents who loved me very much, and always told me that they did, and I felt very safe and happy.

Our universe gets very small when we think of literature as only representative, not creative. And the world just seems kind of mean, and dingy, and cramped when we think of literature that way.

So, in a way, these are companion volumes. What both books are trying to do is infuse how we think of ourselves, how we think of culture, how we think of literature with a little more life. Imaginative life, not real life; made-up life.

sgWhat about the process of writing fiction along with critical essays? Some people say they use different parts of their brain. Did you write these books actually together?

dtI was writing them at the same time. But I didn’t have a notepad in each hand, although I am ambidextrous.

Even before the essay book, starting with Little [Graywolf, 1995]… And this is my own, personal intellectual bent, but I was always a thinking writer. I was always somebody who wanted not just to write a book. From the very start, when I started writing when I was 19, I had a lot of ambition. Not to sell a million copies, or win the Nobel prize, but ambition to really make my work do something. To really try to do something that, when I started writing it, I didn’t know if I could pull it off. To try a big project – not a book, but the book. That’s what I really wanted to do, what I always wanted to do.

What the book is at different moments in one’s life is different. What I wanted my first book, Little, to do is very different than what I wanted to do in this book. But I’ve tried to balance inspiration with the sort of ideas and feelings and emotions and atmospheres that come to me unbidden–I don’t know where they come from – to balance that with dedication and strategy and thought.

sgIt sounds like you’re strong on intention.

dtI’m big on inspiration and intention. Because a novel isn’t just a sort of exercise. Dr. Apelles is–oddly enough, and it probably won’t get interpreted this way– my most heartfelt book, and my most personal too, I suppose. Apelles’ life is a lot like my own, except that I found love, thank you very much, and I was wise enough to grab it when it came my way. So, I’m much luckier than Apelles, and probably much happier for more of my life, too. He’s a quirky guy, I just love him. I would love to spend time with him.

So things always occur somewhat hazy within me – as you say, inspiration and intention. And it happened that they divided themselves out into two projects that occurred at the same time.

But I guess I do feel like there’s a depressing lack of ambition among many writers, not just Native writers. Writers in general, who just want to write a book. They sit down and say, “I just want to write a good story.” You know, it’s a bit disingenuous. They want more than that – I’d like to think they did. You know, “Oh, a good story, that’s so sweet!” Especially writers of color – don’t they have more to do? Shouldn’t we think? But there’s this anti-intellectual strain in America, where intellectualism is somehow bad.

One of the writers who I cover in Native American Fiction, who shall remain nameless, was mad about one of the essays. I showed it to him/her, and they said, “Oh, so you wanted to be an academic.” And I said, “No, I wanted to be a thinker.” But I believe, I feel that we need to put a lot more thought into what we do. Especially when we know that people read our stuff as culture. Even we don’t intend it that way, we know it’s being received that way, so don’t we have a responsibility to keep that in mind when we’re creating?

sgSomething that I come up against in my own community is this idea that thinking, being an intellectual, is a “White” activity. I think that’s terrible when you look at the intellectual traditions that are such a huge part of our cultures.

dtAbsolutely. Very rich ones. The thing is that even if people don’t want to think, there’s still ideas behind Reservation Blues. There’s still ideas behind Love Medicine. And sometimes those ideas don’t work in step with what the writers want those books to do. If you don’t think about it, they’re going to sneak in. And sometimes they’re not very flattering. And in fact, they’re downright dangerous.

I think Reservation Blues is downright dangerous, its ideas about cultural contamination based on miscegenation. Which brings the book into lockstep with The Last of the Mohicans [James Fenimore Cooper]. That’s what that book is about.

So yeah, there’s this sort of anti-intellectualism. And this is true for erstwhile smart books, like Everything is Illuminated [Jonathan Safran Foer], which makes me just want to swallow my tongue.

sgPeople love that book.

dtIt’s terrible. I’ll tell you why they love it – because this is the strain in fiction in general these days. What passes as a “smart” book, the inheritors of Eliot’s and Nabokov’s and Thomas Mann’s efforts. To write books with really simple characters, who have very simple emotions, with language that replaces complexity with quirkiness. So we don’t have any complex language or complex characters, or complicated cross-purposed agendas. Instead of this, we have books that are quirky and extravagant. “Oh my God! His dog’s name is Sammy Davis Jr., Jr.!” (the dog’s name in Everything Is Illuminated). “Isn’t that hilarious!” So this quirk has replaced intelligence.

I’ll tell why people like these books. Because most readers, they don’t trust their own taste. They don’t trust they’re going to understand a” smart” book. But they will, if they get into the mode of reading them.

Reading takes practice, like anything else. Any reader can sit down with The Magic Mountain [Thomas Mann], and enjoy it. But, since readers don’t trust their own tastes, since the market doesn’t trust readers, since editors don’t trust writers, what we have now in these so-called “smart” novels are young adult novels dressed up as literary fiction. Simple plot, simple character, extreme emotions, extreme situations. Like The Life of Pi [Yann Martel], another great example. It looks deep, but it’s really very wide and shallow. “You put a tiger in a boat – isn’t that crazy!” And it’s selling readers short, I think.

That is authors then abdicating any responsibility, with a few exceptions – Richard Powers being one of them. I think he’s just incredible. The Time of Our Singing is just outstanding. It’s about race in America in the last 50 years, and it’s the most amazing book. It’s far more complex than [Toni Morrison’s] Beloved.

There are very few books that are about much anymore. But I’m trying to bring that back, in ways that are enjoyable. Because I think you’re right: people associate that kind of thought with whiteness, or that anything that makes you think is somehow suspect. Especially books about culture – they’re not supposed to make you think. They’re supposed to make you feel. Which is why Ishmael Reed is not a best seller. He should be, but he’s not. Because he makes you think.

sgSo what do you think the critic’s role is in all of this?

dtWell, I think it’s like T. S. Elliot said, that you really can’t have healthy, vibrant literature without healthy, vibrant criticism. And there’s an awful lot of criticism out there about a great many things, but not a lot of it is about Native American literature.

I was putting it to a friend this way last night: “You are now allowed to be a non-Native critic of Native literature, so long as you take the writer’s word for it.” And this is an honest and heartfelt response to a pretty sticky situation. You know how it is, how often we’re spoken for. Everyone else is the experts about us, we’re never experts about ourselves. We were written about as if we were silent for decades and decades and decades.

Native American criticism, growing up in the 1970s and ‘80s, alongside multiculturalism, began to address that, and suggest that these books have value. But the main argument is somehow faulty: That these have value not despite the fact that they’re different, but because they are. So they were read for difference where, in some ways, difference didn’t exist.

Most Native critics are in the same situation as many Native writers, where criticism is a kind of wish-fulfillment. Books are a portal into cultural connection for the writer and the critic. People feel, “I really want to believe that these books perform culture.” Because for Native critics and writers, it’s a way to have a connection with their culture.

I had my own identity issues so long ago, and that’s my private business. I know who I am, and where I belong, and who my people are. I don’t need anyone else to approve it. I don’t need anyone else to give it a thumbs-up or thumbs-down. I don’t need my books to make me feel better about myself, or my place. I skipped all that. I speak Ojibwe, and that’s a great thing. And I don’t need books to do that for me.

Books are for thought and pleasure, and the thrill and magic that literature can bring. And for their inventiveness, not for their truth – except for maybe their emotional truth. That’s what books do for me. I mean, I love that. I can’t live without that. But it’s not about who I am. A lot of people like stories of cultural re-connection. And I’m not interested in that at all.

sgOkay, let’s shift gears, and go in a completely different direction. Let’s talk about Graywolf. I understand that you started out with them, and then you went to a different publisher, and now you’re back.

dtYeah. My first novel I had a big-time New York agent. She shopped it around everywhere, it was rejected about 40 or 50 times. Without fail, the responses that were thorough responses – negative, but thorough – said that the writing was fantastic, but “it’s just not for us.” I think it was largely the result of… . It needed work; what book doesn’t? So there’s that. But I think it was also because I didn’t perform, culturally, the way that they wanted me to. There are no feathers, there’s no ceremony, there’s no reclaiming of Indian-ness, there’s no Indian pride. It’s just living. So it confused a lot of people, and they rejected it.

And then, it showed up in front of Fiona [McCrae, Graywolf publisher]. She was new at Graywolf. And she just got it. I don’t think it had to do with what Graywolf is, or where it is, or that it’s a small publisher, or that it’s an independent publisher. As the publisher, as the editor-in-chief at Graywolf, Fiona just got what I was trying to do. And she loved it, and was an early champion. She helped me whip it into shape, and she helped me fix all the problems that it did have. And I was thrilled – I was just absolutely thrilled. I was 24 when it came out.

So Graywolf had vision. And Fiona had vision, and the rest of the staff as well. I’m in a market that doesn’t really have much. I don’t think that Graywolf has it because they’re a small publisher, I think they have it because they’re a special place. And increasingly, they’re not small. They’ve got reach, and they are well-respected. When they have a book out, people perk up. They have this brand identity. And they support their books.

Unfortunately – although this is changing at Graywolf – when Little was published [1995] they couldn’t pay very much. They sold the paperback rights to Picador, this humongous publisher. And then Picador bought the next novel [The Hiawatha]. Picador didn’t know what to do with it. The editor, who was a good person, just didn’t know what to do with it. The publicist was brand new and didn’t care, never read it. A publicist at a big publishing house isn’t going to read the book. I mean now it’s different, it’s being reconfigured, but St. Martin’s – how many books are they publishing a year? Hundreds and hundreds and hundreds. On the literary list, they’re probably publishing 50 books a year. So they didn’t really help with the book, and they didn’t know what to do. And that book had its faults, too.

And then, this last year and half was just hellish. I switched agents and found this agent I just love. He read Apelles, and he just loved it to death. And he said, “Yeah, we’re going to sell it. I’m so excited.” And then two months down the way, he dropped off the face of the earth. He had a drug problem. He drained his bank accounts, he disappeared. His business partner dissolved the business in his absence. All of a sudden, I had no agents.

I interviewed 20 agents in New York. Most of them said yes. I went with one, and after the one hit the skids, I went back to the other 19, and you know what they all said?

sgWhat?

dt“Fuck you. You turned me down, now I turn you down.” The egos are just immense. So I tried to sell my work on my own. I was like, “Okay, let’s go!” And I had a few offers from different publishing houses. And then, while I was still searching, I found a guy who I think is just sterling, he’s a prince. I was just, “I need to take a urine sample, just to make sure.”

sg[Laughing]. Who could blame you?

dtYeah. I just felt like everything was falling apart – everything. I was so stressed out. I felt adrift. I felt really abused by the industry – both by publishers and agents. I felt that it was a shallow and thoughtless and commercial industry of people who like to hold themselves apart and above from other media, like film, but they’re not. I was really pessimistic and depressed about it all.

And then I re-connected with Graywolf. It’s not an exaggeration to say that they restored my faith in publishing. They’re such an amazing group of people – all the way around. They’ve worked so hard on the books, and so diligently, and so carefully, and they love them so much. And the love shows.

I mean, it’s a happy time – every part of the process has been happy.

Come back to Thinking Souls in a few days to read an interview with with Kyle Hunter, who designed Treuer’s book covers, as well as reviews of both books. And don’t miss your chance to add your voice to the mix – the Thinking Souls online book club is the place to hash out both formed and incipient ideas about art and writing in Minnesota!

Next month: We’ll talk to Arleta Little of the Givens Foundation for African American Literature about their work promoting and preserving Black literature. Pick up a copy of Harriet Jacob’s Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, an American classic and a Givens Foundation re-issue, for September book club discussion.