THEATER: Comedy in the Long Shadow of the Reich

Playwright Matthew Everett weighs in on Walking Shadow Theatre's new production, "Amazons and Their Men," which offers a clever take on the thorny character of the Nazis' favorite filmmaker, Leni Riefenstahl: on stage through November 1.

“MAYBE IM TOO INCLINED TO GO EASY ON A PLAY that makes me laugh,” my friend said after taking in Walking Shadow Theatre Companys latest production, Jordan Harrisons Amazons and Their Men. We were sitting down to dinner following the show (and not a very late dinner either, since the production clocks in at a brisk hour and fifteen minutes total, no intermission). My friend could tell the play was bugging me for some reason, and he wanted to put his lack of a need for a critique in some context.

She is made of wolves and stars.

Personally, I think simply finding a play funny is, on its own, a completely valid reason to like it. And Amazons and Their Men is a very clever play – both smart and funny. The four person cast turns in a quartet of strong performances, some stronger than others, but the bar for actors is set very high in this production. Amy Rummenies direction is, as ever, sharp as a razor and keeps the action humming along at a healthy clip. The artists of the design team outdid themselvesmost especially, Andrea Heilmans set, Jenny DeGoliers lighting, Michael Croswells sound and music, Jenna Papkes properties, and Renata Shaffer-Gottshalks costumes. The play is full of quotable lines; I can understand why the press kits include a copy of the full script. One could spend the whole night jotting down turns of phrase that captivate the ear and the mind and, in so doing, end up missing the next thing Amazons has up its sleeve. Walking Shadow has, once more, taken a fresh, interesting script grappling with fascinating issues and fashioned a great production out of it. I highly recommend you see it.

If thats all you need to know and you dont have much interest in my dramaturgical discomfort with the script, then stop reading now. Go reserve your tickets and skip the rest of the review. Nothing Im about to say below mitigates the fact that I think Amazons and Their Men deserves the widest possible audience.

Here was a woman to be interested in.

Amazons and Their Men is loosely inspired by the life and art of Leni Riefenstahl, a director whose film, Triumph of the Will, made a movie star out of Hitler and which is, still, today considered one of the best pieces of propaganda ever made. A better commercial for the Third Reich you can’t find anywhere. The film, for all its cinematic virtues, has also been a flashpoint for ongoing debate about an artists responsibility to society in the work they do. Riefenstahl outlived Hitler and World War II and even the 20th century, dying at the ripe old age of 101 in 2003. Her actual connections to or sympathies with the Nazi party were a slippery subject she ducked and dodged for much of her very long life. What exactly is the culpability of an artist whose successful work helped enable a horrific cadre of men to sell their inhuman mission to the general public as something impressive, even magnificent? If youre going to muck around in the notions of the importance and influence of Art with a capital A, theres no more compelling case study.

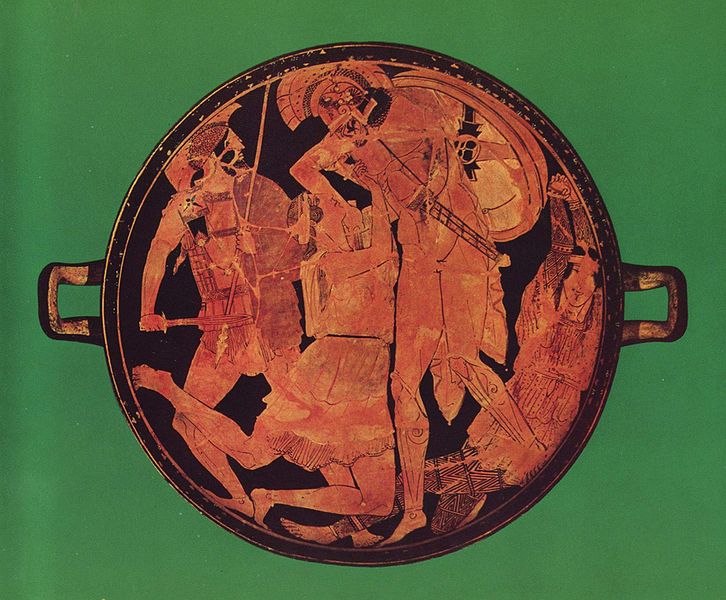

After making her films for the Reich, Riefenstahl was set loose to create a film version of the legend of Penthesilea, the Amazon Queen who, depending on whose version of the story one listens to, bewitched or was bewitched by, killed or was killed by, the equally legendary Achilles. When Germany invaded Poland, filming stopped and the screenplay was lost. Only a rough outline of the key scenes in Riefenstahls version of the story survives. She wasnt always the most accomplished actress or the most compelling screenwriter, but the visual impact of her films was never less than stunning. Riefenstahl made a lot out of a little, and when full resources were at her disposal, she created masterpieces.

Switch the name Frau for Leni Riefenstahl in the story above, and you have a pretty fair biography of the lead character in Harrisons play, sublimely enacted by the wonderful Zoe Benston. You couldnt put such a thorny character in better hands. My friend entered the theater never having seen Zoe on stage before; he left the theater, as I knew he would, a fan.

Sometimes I die more than once in the same film. Its my specialty.

Equally terrific on stage is Christine Weber as “the Extra” – the plays primary narrator (though direct address to the audiencewhether by the scripted characters or the parts they, in turn, act out in the film-within-a-playis a device used frequently throughout the production). The Extra has a special bond with the Frau (that I wont divulge here) which makes her uniquely qualified to observe and tell the story of this woman. The Extras sympathy for the plight of her fellow actors, as well as that of the Frau, helps the audience to connect with all of them in ways which might not otherwise have been possible. The character carries a lot of the freight for this story, and Weber handles the balancing act most skillfully.

_________________________________________________

Leni Riefenstahl wasnt always the most accomplished actress or the most compelling screenwriter, but the visual impact of her films was never less than stunning.

_________________________________________________

Erik Hoover does quadruple duty as “the Man,” playing an actor conscripted for the film production out of a concentration camp. He’s also the Fraus romantic interest and leading man, Achilles in the film, as well as the off-screen Minister of Propaganda and, at one point, even the Fraus mother. “The Boy” (Grant Sorenson), who delivers the telegrams from the Minister of Propaganda, also gets drafted into Riefenstahl’s film for the role of Patroclus, Achilles young companion. When the relationships between all the characters start blurring the emotional lines between on-screen and off-screen life, things get more than a little complicated.

Theres going to be a war here, too. Theres no need to make one up.

So what bugs me about all this? Amazons and Their Men is a really good play. The thing that bothers me is that it could have been (and still could be) a great play. The seeds of the great play are already there. The characters, the structure, the larger thematic questionsthey’re each begging to be given free reign and deeper exploration. Instead, as the play is now, much of the story feels rushed and distant in the telling. The narrative, as a whole, skitters across the surface without ever really diving deep into the murky waters below. I dont expect any play to give me the answers, but I do expect a great story to fully lay out the questions. The playwright, Jordan Harrison, is clearly capable of writing the great play. If the script we do get isnt proof enough (though even with its flaws, it is plenty for me), his biographystrewn with awards, productions, and commissionsfurther makes the case. I have a feeling Amazons‘ brevity lies at the root of what’s bugging me about the play. Why did the whole complicated story have to be crammed into less than an hour and a half? From personal experience, I know playwrights sometimes get boxed into a shorter timeframe than they were planning on (both to develop a script and in terms of the final running time permitted them). Sometimes necessity dictates that you put things in shorthand when youd prefer to give them a little more room to breathe.

For example, it feels facile to use Nazis as simple shorthand for evil. The danger with that approach is it threatens to turn Nazis into cartoon villains. Not only does that undercut the sense of menace and lower the stakes for everyone involved, it also threatens to downplay the seriousness of the Holocaust. That isnt the plays intent, but its the territory you tread in when a German accent becomes the equivalent of a villain twirling his moustache in an old melodrama. More than sixty years after the fact, I dont think we can safely make the assumption anymore that everyone will know and understand the gravity of the Holocaust in the same way without a hint or two, some context.

Im certainly not arguing for a full recounting of the litany of evils involved in the Nazis Final Solution. But the deliberate lack of detail in a number of places in the text is evidence of the playwright’s perilous leap of faith; he’s trusting that the audience is going to fill in all the script’s narrative blanks on their own. (Though, I do have to admit, when that first silent movie title card Prologue appeared, a little chill went down my spine. It didnt just say “silent movie” to me. In my mind, what I saw on the card was Nazi font: a very nice, creepy touch by the production’s design crew.) A little more specificity throughout would have fleshed out both the characters and the situations in which they found themselves trapped.

But that’s not to say Amazons has no nuance in its depiction of the Holocaust: the play does touch on the plight of the gypsies as well as the Jews, and it gives the subject of sexuality as grounds for extermination a lot of ink. (In fact, Amazons and Their Men sometimes seems as obsessed with/repulsed by gay sex as a conservative politician running for office.) The script hints more than once that the Fraus film set serves as a temporary sanctuary for people who might otherwise be shipped off to the ovens. Whether this offer of refuge is a product of genuine affection and/or outrage from the Frau, or serves some kind of penance for past artistic misdeeds is unclear.

_________________________________________________

It feels facile to use Nazis as metaphorical shorthand for “evil:” the danger of that approach is that you’ll turn them into cartoon villains and unwittingly undercut the menace and seriousness of the Holocaust.

_________________________________________________

Art about art more often than not leaves me cold. Or worse, it bores me. To be honest, Amazons and Their Men sometimes skates perilously close to pretentiousness in its concern for the importance of art and artists to society, but this wasn’t what bothered me about the script. There’s a quote, not from the play, but from a noted theater artist (the source and specific wording of which eludes me at the moment) that has to do with looking at the past, and the fact that sometimes history wont ask, and society wont ask, how something horrible could have happened; instead, they will ask why the artists were silent. There’s an interesting conflict rooted in the fundamentals of human behavior evident in that notion. Artists may sometimes be canaries in a coal mine, the first to sound the alarm when faced with evil, even at great personal cost. On the other hand, artists may also choose to follow the opposite course, offering up their talents in service of terrible ends, rationalizing their self-preservation instinct after the fact through the good art they make subsequently.

Anything outside Gods design we can choose to abide, or not to abide.

The device of direct address to the audience as employed throughout Amazons is a double-edged sword, and the script gets both sides of the blade. The fact that everyoneactors, stage characters, the players in the film-within-a-playis talking right to the audience allows the story to more fully engage the viewer’s imagination. Enlisted by such direct appeal, the audience assists in creating a stage picture in their minds, so the production itself neednt be literal and weighed down by multiple scene changes or mountains of props and furniture. But this technique also holds the audience at arms length emotionally. We arent allowed to feel for the characters, to immerse ourselves in the moment. The theatrical moment is thoroughly annotated for uswe are told what the characters feel, what we should be feeling, and we are constantly reminded that we’re watching not just a fiction, but a fiction-within-a-fiction. Thats a lot of winking at the audience, and it carries the real risk of drawing too much attention to the artifice of telling the story.

In other words: a really good play leaves me thinking, That was remarkably well put together and executed. A great play though, allows me, even demands of me, not just professional admiration but a full range of visceral feelings. While I appreciate that Amazons and Their Men never tried to play for cheap sentimentality or emotional impact it hadnt earned, I longed to care for these characters more than I did. The fine acting and directing went a long way toward making up for the lack of a beating heart to animate the cogs of the script; but, without that emotional center, accomplished execution alone can only go so far.

Why do you have to imagine another world?

Where else will we go when this one ends?

All that said, again, I highly recommend this production. Actually, I love that Walking Shadow is three for three with me right now. Theyve produced three plays in a rowThe American Pilot, Shakespeares Land of the Dead, and Amazons and Their Menwhich, on some level and as much as I admire them, bug the hell out of me. When Walking Shadow puts on a play, I am never a passive audience member. And thats all too rare, even in a town up to its neck in quality theater offerings, large and small. Quibbles aside, Amazons and Their Men is smart, funny, engaging theater. Go see it. Maybe youll get lucky and itll bug you, too.

What: Walking Shadow Theatre Companys Amazons and Their Men

Where: Pillsbury House Theatre, Minneapolis, MN

When: Performances run through Saturday, November 1 (Thursdays through Saturdays at 7:30pm, Sundays at 3pm)

Tickets: General admission $16 ($14 students and seniors)

About the author: Matthew A. Everetts play Dog Tag is currently being performed as part of the short play showcase Bruschetta 2008 at Appetite Theatre in Chicago. His play Leave, produced by afterdark theatre company, recently completed a successful run at the Bryant Lake Bowl. Matthew is the recipient of a Drama-Logue Award for Outstanding Writing for the Theater, and he is a three-time recipient of support from the Minnesota State Arts Board. He holds a Master of Fine Arts degree from the Yale School of Drama. Magicword Theater produced a popular double bill of his short plays The Bronze Bitch Flies At Noon and Dog Tag as part of the 2008 Minnesota Fringe Festival. His blog about the Fringe can be found online at Twin Cities Daily Planet. Sample scenes, monologues, and further information on Matthew and his work can be found on his website, www.matthewaeverett.com, and of course, at www.mnartists.org/matthew_everett.