The Vicarious Journeys of Derrick Burbul

Suzanne Szucs describes a fascinating exhibition that explores what can be captured in the box of a pinhole camera. It's at the Duluth Art Institute through October 24.

We all like to think that art communicates something universal. Unfortunately, much high art of late has the effect of turning off the average viewer. Vicarious Journeys, Derrick Burbul’s modest exhibition of pinhole photographs shown together with the cameras that made them and statements from the individuals who lifted the shutters, makes an eloquent plea for art as a tool for communication.

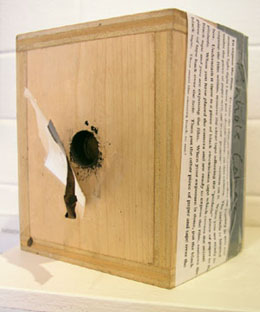

In an age where the ante has been upped for fine art photography and bigger, shinier, more digital is considered better, Burbul’s exhibition is refreshingly faced in the other direction. Begun in 1998 as part of his MFA thesis, Burbul began making pinhole cameras out of old photo paper and film boxes and sending them off to friends and acquaintances with the instruction to make a self-portrait in a favorite place. The imagemaker would then return the camera via parcel post along with a statement describing the place or the experience. Burbul exhibits the letters alongside the images, as well as the cameras, although the box cameras are possibly the least interesting aspect of the show – seeing one probably would have been enough. The result is an uneven exhibition of images, but themes emerge, speaking to the nature of memory and photography.

A pinhole camera is simply a box, with a hole in it and some sort of shutter attached: in this case, mostly black electrical tape that can be removed and replaced once the image is exposed. It is supposed that the first photograph made by Niepce in 1826 was made with a pinhole camera, although by the time photography was officially patented by Daguerre in 1839, cameras and optics were relatively advanced, thanks to their use as tools to assist painters in visualizing their scenes.

Optically, there is a perfect size pinhole for any given focal length, meaning that the image can be rendered with exact focus, infinite depth of field – an eerie thought in itself. Most fine art pinhole photographers, though, opt for a degree of chance in their image and therefore do not create a camera to exact specifications. Subjectivity—the imprint of the photographer’s self–is associated with mediations in the image such as blurriness or distortion, and such photographers work to subvert the inherent objectivity of the camera by courting such mediation.

So it is with Burbul’s cameras and the images they produce. He wants the camera to capture the subject’s sensibility, to truly be a conduit between himself and these distant subjects. The irony is that the images are rather uniform. The cameras themselves are not constructed differently enough from one another that they lend much individuality to the subjects. Rather, it is the subjects’ letters that single them out and create much-needed context for the images.

Philosopher Roland Barthes referred to photographs as “little deaths.” This theme of loss emerges in both the stories and images of Burbul’s subjects. One photographer writes, “We often are born and die in a bed,” yet instead of the bed she thinks she has pointed the camera at, she captures an iron, a domestic symbol of everyday experience made lovely and monumental by soft light. A farmer struggles to capture his sheep, as he knows they won’t stand still for long. In his letter, he confesses sadness that his way of life is ending, as he is no longer able to farm due to illness. As a result, making the image has taken on a deeper meaning. Others reminisce on the loss of a dog, a forest, a moment gone forever.

Some of the most eloquent images are of interiors. There is an intimacy augmented by the pinhole effects of soft light, blur and slightly distorted wide angle. One woman writes, “I thought I should wait for something special,” but ends up photographing her grandmother in her room. Although the woman is completely invisible, there is a sense of loss and sadness present in the dark room; a guitar is thrown casually on an unmade bed; a blown-out window is too high to provide a view. On deeper inspection, one sees a faint blur of grandma, hunched over in her chair, her long hair brought up in a bun. It is as though she has just emerged and will fade again. I can’t imagine that there could be any more special photograph to make than this brief glimpse of a life passing.

So what role does Burbul play in this equation? It is interesting that the imagemakers themselves do not get to see the photographs until Burbul sends them a copy. Their control exists in choosing the location and props, setting the camera where they think it will record, opening the shutter and writing the letter. Unless they are familiar with how pinhole works, they may or may not be successful in creating what the viewer might consider a quality image. Their effort is faith, as is Burbul’s to trust that they will carry forth his intention and meet his goal. I believe that the success of this exhibition lies not in the photographs (who do these images belong to, anyway?) but in the willingness to communicate beyond the borders of a product. Here art equals sharing experience and vulnerability. Burbul as facilitator has been lucky to be so well attended by giving souls.

Vicarious Journeys is showing at the Duluth Art Institute through October 24.