The Secretary

Camille LeFevre reflects on the evolving sexual politics and significant historical and cultural moments marked by the Goldstein Museum of Design's exhibit, "How Secretaries Changed the 20th Century Office: Design, Image, and Culture."

“The executive who finds a well-trained female can count himself lucky indeed.” As I peered into the glass case housing magazine spreads from the 1950s about the “new working woman” — the secretary — the above quote stopped me cold. The sentiment’s forthright sexism (executive = man; well-trained female = woman? Or monkey?) was not only disturbing, it was bone-chilling.

As a prelude to the Goldstein Museum of Design‘s exhibition How Secretaries Changed the 20th Century Office: Design, Image, and Culture, the message in the case underscores a painful truth made visible in many of the artifacts included in the show, which traces the development of “the secretary” as business professional, cultural avatar, and sex object from the early 1900s through the 1970s.

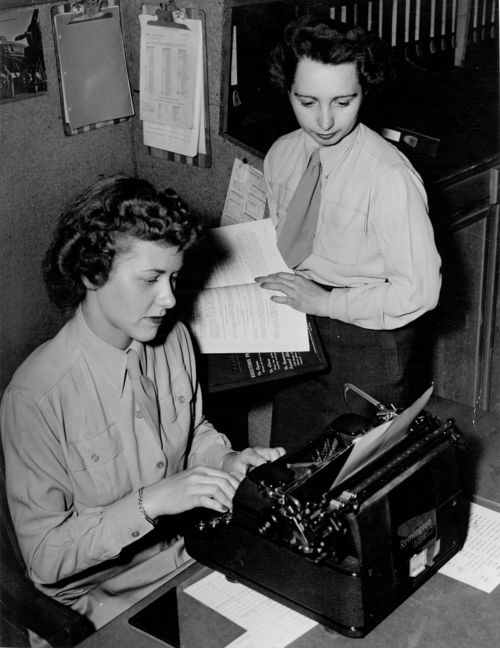

This exhibition is an extension of doctoral candidate Midori Green’s dissertation; Green organized the show in conjunction with her adviser, Katherine Solomonson, associate dean of the College of Design at the University of Minnesota. Fascinating displays of clothing, furniture, office equipment, and photographs explore how the influx of women into business, starting in the early 1900s — as “typewriter girls,” stenographers, and secretaries — allowed corporations to flourish; these new working “girls” generated the extensive paper trails necessary to keep products and profits moving throughout a growing industrial, capitalistic system.

The sexualization of women who worked in offices alongside industry’s men, their bosses, kept ardent pace with working women’s growing independence. Postcards portraying the office as a place for a young woman to find a husband quickly evolved into salacious, comic book-like depictions of lascivious men grappling with curvaceous women over the office desk. (Flashcards on what constitutes sexual harassment, anyone?) By the 1940s and ’50s, the age of the “sexy secretary” in this exhibition, glamorous secretaries in minks and couture began to strut through Hollywood movies, stealing husbands from their wives. In the show, cards and various tsotchkes (I even saw a dishtowel among them) depict a parade of “naughty” cartoon secretaries with their bosses, in various stages of undress and fornication.

During mid-century America, new efficiency methodologies, from Taylorism to Fordism, had spread from the factory assembly line to the secretarial pool, as photographs of women seated at regimented rows of identical desks make clear; the interior shots of Frank Lloyd Wright’s iconic Johnson Wax Building are exemplary of this push to integrate mass production’s efficiencies in the office. Designers of the time were also amply rewarded for reconfiguring desks, chairs, and equipment to better suit the contours of the female form, so that “the efficient office and the efficient body were combined into one smooth mechanism to keep paperwork moving.” Conversely, the curves associated with the “sexy secretary” inspired designers to soften the edges of typewriters (one IBM is pink), desks, and chairs — simultaneously feminizing and eroticizing the business environment.

The curves associated with the “sexy secretary” inspired designers to soften the edges of typewriters (one IBM is pink), desks, and chairs — simultaneously feminizing and eroticizing the business environment.

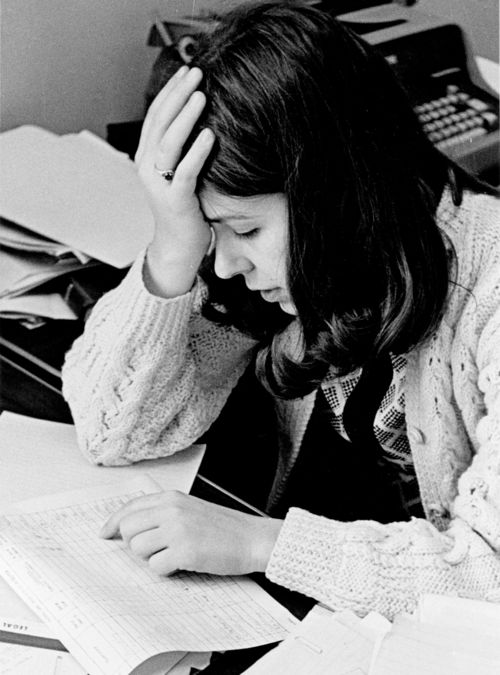

By the ’70s and ’80s, the secretary had morphed into the less sexually charged “administrative professional.” New technologies introduced yet more efficiencies in the office, but those “efficiencies” often boiled down to more work for women in that position, who saw more demands on their time and an increased share of responsibilities. And still, those early stereotypes lived on. Pop culture’s nostalgia for all things mid-century — the furniture, glassware, mid-afternoon cocktails, and the sexy secretary — is manifest in the popular television show Mad Men; it’s fitting, then, that Mad Men‘s secretarial siren, the Marilyn Monroe-like character Joan Holloway, in particular, is highlighted in the exhibition.

For those of us who came of age in the ’70s, when ideals of mid-century glamour and its clear-cut distinctions of race, gender, and sexuality were rent asunder by the advances in civil and women’s rights, How Secretaries Changed the 20th Century Office is both a blast from the past and a reminder of how little some things have changed. Just as this exhibition addresses “continuing questions about the complex roles design and popular culture play in the production of opportunities, constraints, and images associated with working women,” so also do its messages and artifacts legitimize an arena of “women’s work” at once denigrated by and essential to a capitalist society.

Victor Pellaire, writing in the New York Times in 1946, viewed American secretaries as creatures of frightful power and brash energy, especially when compared to his beloved and more laissez-faire French women. To his mind, American secretaries were less “well-trained females” than “business amazons,” an attribution that, despite its intended disparagement, speaks eloquently to the role of the office denizens who have, for more than a century, kept the machinery of industry and corporate America running. In How Secretaries Changed the 20th Century Office, their invaluable contributions are honored, just as the sexualization and harassment their professional engagement and fiscal independence engendered is laid painfully bare.

Related exhibition: How Secretaries Changed the 20th Century Office: Design, Image, and Culture will be on view at the Goldstein Museum of Design and the University of Minnesota through May 23.