The Renegade: Pranks, Performance and Billy X. Curmano’s Idea of Fun

Maverick Winona-based performance artist Billy X. Curmano chats with Matt Konrad about the artistic impulse that has driven a long career of daredevil feats, political chutzpah, and making art his own damn way.

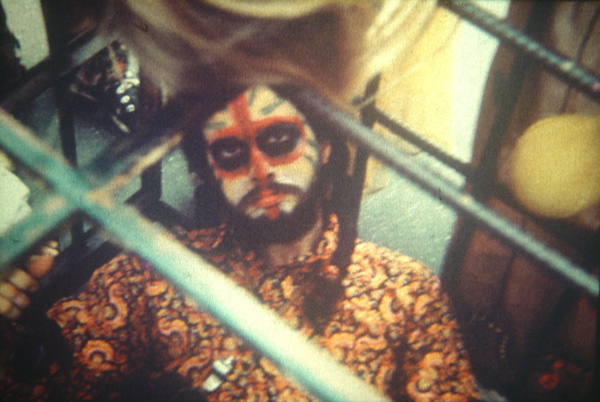

BILLY X. CURMANO, PERFORMANCE ARTIST AND PROVOCATEUR, doesn’t really care much for conventional wisdom. Take the stereotype that art is the province of dour, black-turtlenecked urbanites. Take it, and then kick it as far away from Billy as you can. He grew up in Milwaukee and spent time in the East Village, but, ultimately, he decided to make his base of operations a picturesque corner of Southeastern Minnesota. From there, he plans extravagant performance pieces, publishes wry, pun-filled newsletters, and toys with questions right down to the “what the hell is art, anyway” level.

Billy’s work challenges the idea that grand adventure is the exclusive right of those who can afford it. Bored billionaires might be traveling around the world in balloons and paying to be towed up Mount Everest, but they’ve got nothing on Billy Curmano. He decided it’d be an eye-opening performance project to swim the Mississippi River from Lake Itasca to New Orleans—and then, over eleven summers, he did just that, landing in the Big Easy on Billy X. Curmano Day, 1997, thus culminating Swimmin’ the River his best-known and grandest-scale performance.

Though you might not guess it from his ready smile and the graying mustache, Billy Curmano is a rebel through-and-through, doing his own damn thing and creating performance art, music, sculpture, and an artistic atmosphere that’s impossible to ignore.

“I just like to do work that is interesting,” Billy says on the phone. When we talk, he’s in the midst of a massive move from his studio space in Rushford, which suffered extensive damage during the Winona-area floods last summer. “I like the idea of getting out to different audiences and doing work that intrigues them, whether they understand it as art or not. I like tweaking them,” he explains.

“I think about it the way I think about homosexuality—if someone’s secure in their sexuality then they aren’t homophobic. I feel secure enough about my work that I like to get a response from the audience, but if it’s not the right response, I don’t mind. You just have to please yourself. If you’re doing work just to please other people, you’re not getting at the root of your soul as an artist.”

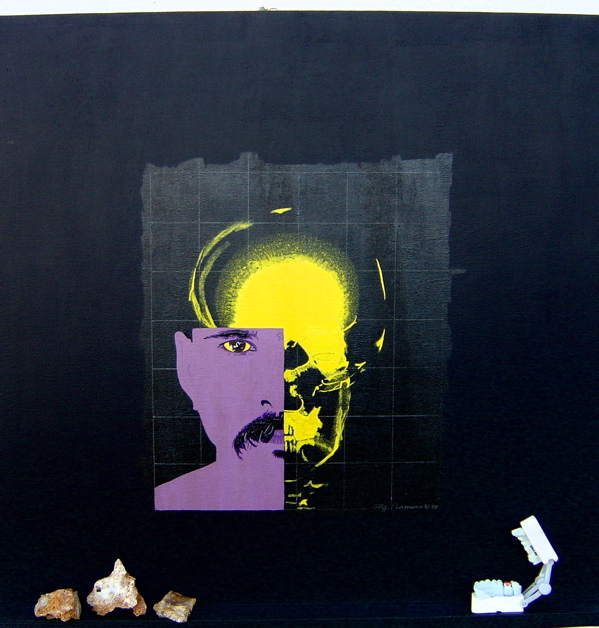

An overview of Billy’s career indicates that, for all of his wide-ranging work, he has indeed stayed true to his roots. He trained as a sculptor at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, and returned from a stint in Vietnam as a full-time artistic rabble-rouser. In time, he added music and guerrilla street theater to his repertoire. The twin poles of his work have always been to raise perceptions and to have a little fun. These aims are evident throughout his oeuvre, from his early anti-war installations at UWM to a “performance fast” in the Mojave during the Y2K freakout, and in his Buried Alive project, in which he spent three days entombed near Winona in an effort to bring art to the dead. And most of all, this commitment to serious-minded fun is apparent in his signature Swimmin’ the River project, which managed to make an environmentalist statement, an individualist argument, and a decade of entertaining summers all at once.

“The Coast Guard came after me just past St. Louis,” he recalls, thinking about one of the most intense days of the swim. “It was a really tough run through a major shipping center, about 100 miles with coastline and barges. When we were going away from [a welcome ceremony at] the Arch, this Coast Guard boat came up behind us. I yelled at them ‘I’m okay, fellas, thanks for checking.’ Through the megaphones, they yelled back. ‘It doesn’t work like that.’”

As is his wont, though, Billy kept on swimming. His crew in the support boat enlightened the Coast Guard on the project, eventually making even them believers. (Billy was a bit disappointed that he didn’t get to argue in court about people having the same rights as, say, shipping barges, but that didn’t dampen the spirit of the run one bit.)

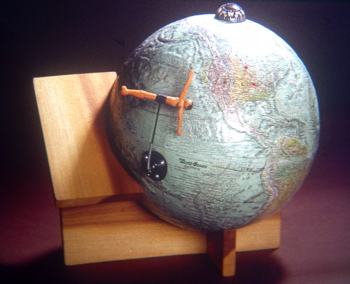

The Mississippi River swim is also exemplary of Billy’s dedication to true multimedia pieces. The work encompasses more than a one-time performance. These days, he still frequently exhibits his self-produced documentary about the event, taking a break to perform songs including “River Rap;” and in conjunction with all this, he shows a variety of mixed media sculptures he created to record the event. In fact, some of his work still includes the Mississippi itself: he’s used water collected from the river in subsequent pieces, in one case mixing a commemorative vial of Big Muddy with the Arctic Ocean (whose shores were reached, in true Billy fashion, via public transportation).

With Billy’s tendency to mix the ephemeral with the lasting in his work, he has, in effect, built a well-traveled bridge between performance art and visual art. He’s building similar bridges in other areas, too. The floods in the Winona area forced him into a new studio home (which, as it turns out, also had some water problems—he wryly notes that FEMA offered him a dehumidifier to help with the move). He’s now building it into a complex that will include a personal studio, a home for his New X Art Ensemble, a rotating cast of musicians, and an alternative-to-the-city performance space and gallery. The Ensemble performs frequently both at home and in the Twin Cities, and Curmano is also working on other projects like an annual “Anti-Shakespeare Festival” to run in conjunction with Winona’s Shakespeare Festival; the first, two years ago, ended with Curmano having to canoe around an island looking for campers that had spent the night. And he continues to shoot videos, craft sculptures, and design sets for his performance work. Overall, his tendency to mix the ephemeral with the lasting allows him to shifty freely between performance and visual art.

For a guy who couldn’t give a damn about “rules” in the art world, his underlying aim is a serious one. He’s dedicated, through his work, to leaving something of himself behind. “I began working as … the term ‘traditional artist’ doesn’t really apply, but I made objects,” Billy recalls, thinking about how far he’s come as an artist. “The sculpture department at my college didn’t take real kindly to performance art. It wasn’t heavy enough. But one professor I had, he once told me, ‘Billy, we were always proud of you, because you didn’t lose sight of the object.’ And I haven’t.”

About the writer: Matt Konrad lives in Minneapolis, where he writes about everything from soccer to cocktails. His work appears frequently in Metro, and you can visit him online at The Cash Box and the Taste Mafia. When possible, he chooses to do his river trips via canoe.