The Medium Itself: McKnight Photographs

Mason Riddle writes on the 2007 McKnight Fellows show at the Minnesota Center for Photography, featuring Kristine Heykants, Orin Rutchik, Mickey Smith, and Angela Strassheim. It's a mixed bag with some striking images. (Up through October 8.)

The McKnight Foundation Artist Fellowships for Photographers program has come to roost in what seems its predestined home, the Minnesota Center for Photography. After a 25-year peripatetic journey, beginning at Film in the Cities in 1982 and then moving on to the Department of Art at the University of Minnesota, the program has supported 130 artists (some as many as five times) to date and stands to flourish now that it is anchored by an organization dedicated exclusively to the medium.

Like all such exhibitions, the New Photography: McKnight Fellows 2006/07 is a mixed offering with no curatorial premise other than the medium itself. The aesthetic practices of Kristine Heykants, Orin Rutchick, Mickey Smith and Angela Strassheim, who were selected as fellows a year ago based on the quality of their work, are ostensibly linked in that they all work in color and trade enthusiastically in irony for the visual/conceptual impact of their work.

Heykants’ translucent color coupler prints of women posing in contrived environments are displayed to dramatic effect in illuminated light-boxes in a darkened room. Stylish and ironic, these tableaux vivants are part and parcel of a contemporary art practice done by Cindy Sherman and former Minneapolis resident Bruce Charlesworth, among many others. The women are static and expressionless, revealing nothing, and conferred roles by their dress and staged surroundings– one is an equestrian on a bay horse, another is fashionably dressed in what appears to be vintage 1940s kitchen, a third folds clothes in a laundromat and still another stands alone at a train station. All glance furtively away from the camera, as if distracted by some unanticipated event.

In Heykant’s photographs, the women are types, carefully conceived protagonists acting out oblique narratives. Italian Scooter is the epitome of Heykant’s eye for artifice. Here, a woman in a 1960s Courreges-like dress stands with a red Vespa, an image so pristinely stylized and constructed that it convincingly legitimizes its own faux reality with elegance and humor. So perfect are these images in their juncture of the mundane and the exceptional, superficiality and reality, one wonders what Heykant’s next step may be?

Orin Rutchick mines territory mined too many times before: photographs of people taking photographs, in this case for a project he calls Push Button Memories. For his subject matter he chooses four tourist attractions, photogenic in and of themselves– Graceland, Alcatraz, the Kennedy Space Center and the Hoover Dam – with the underlying thesis that people visit these sites more to be photographed in them, thus inserting themselves in the history and fame of such place, than actually to see/experience the site itself. Of course, the very nature of his investigation squarely inserts Rutchick as a player in his own project. (One can only imagine the many times Rutchick appears in the photographs of others.)

In the end, the sites are more provocative than the camera-totting tourists that Rutchick records. Do photographs of people taking photos of other people reveal much of anything? Maybe not. By contrast, Rutchick’s panoramic, black and white images, two of each site, are compelling. Sans tourists, they evoke images of a previous era and his vision captures agilely the breadth and the spirit of these sites, unfettered by any predetermined approach.

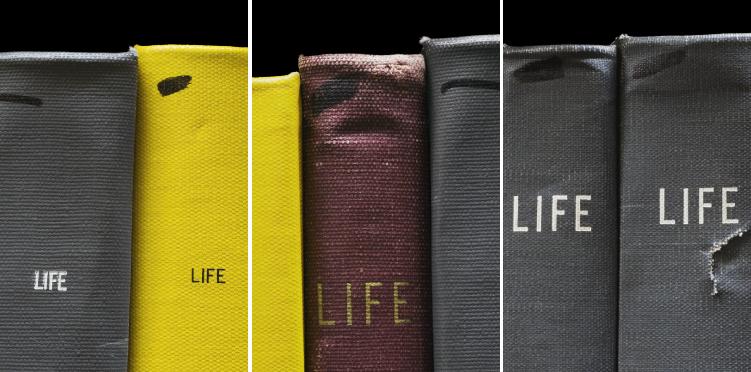

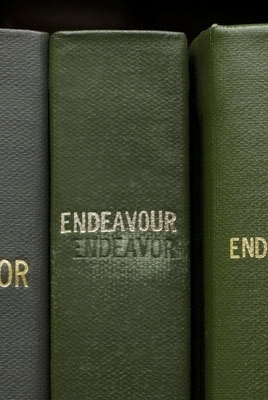

Mickey Smith is the only fellow not to focus her camera on people. Since 2004, she has photographed bound periodicals and professional journals on shelves in public libraries. Noteworthy is that Smith’s inkjet photographs are not staged but images of the tomes in situ. She photographs the books as found objects, neither manipulating their order on the shelf, nor illuminating them artificially. With the repetition of a single, minimalist form, the images are provocative, their formal reading determined by the edge of the photograph. The images also take on an associative quality: we are prompted by the titles on the colorful spines of the bound volumes, – Life, Sex, Cancer and Endeavour – to define our own relationship to the word’s meaning and how the books’ physical mass is countered by the abstract notion of knowledge.

Smith’s ongoing project parallels a researcher’s pursuit to find the right book in the stacks. Her quest is to document these reservoirs of information in their concrete physical form, before they disappear completely to exist only in cyberspace. These images underscore the irony that these books, once revered as the ultimate containers of the thoughts and ideas of so many, will soon be available only to those with the electronic capability to access them.

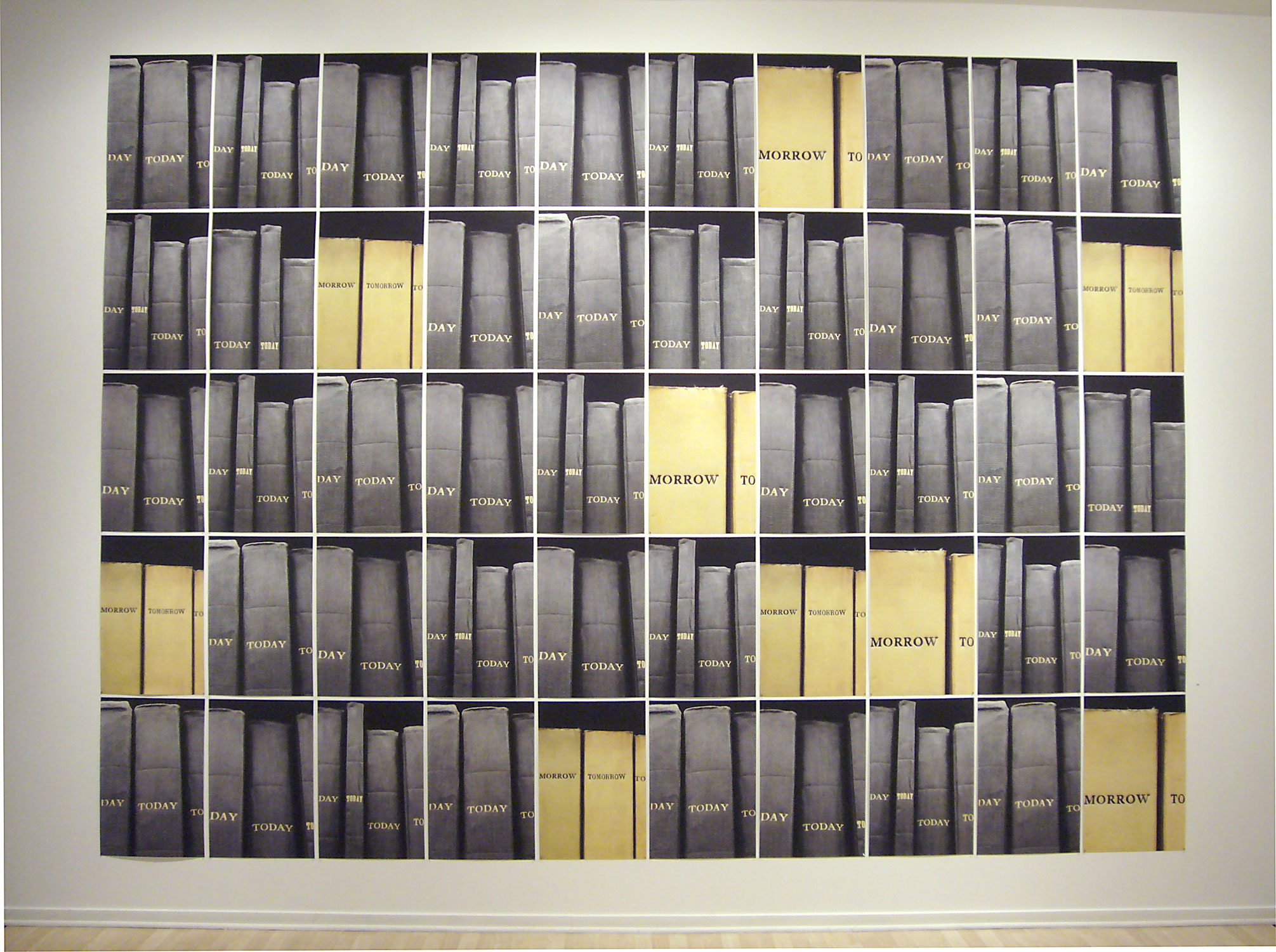

Smith works in series, which she appropriately calls Collocations, creating single images, diptychs and triptychs. With the McKnight exhibition she has expanded her reach with a work titled Collocation No. 4 (Today), a mural-scaled work comprising 50 images of grey and yellow journals titled Today and Tomorrow, installed, unframed, in a grid format. Given the prominence of monumental photographs in the last decade by likes of Andreas Gursky and others, it is not surprising to see Smith experiment. Scale has its own power and Smith has exploited it effectively. Viewing her individual images, we are Lilliputians, looking at books that are four and five feet tall. With Collocation No. 4, Smith has constructed a more realistic, physical relationship between viewer and books; it is as if we are in amongst the stacks, ourselves.

Angela Strassheim’s color inkjet prints are staged vignettes that take the notion of tableau vivant a few conceptual degrees beyond Heykants’ work. Effortlessly, Strassheim puts the viewer in the position of voyeur. We witness her poseurs, usually depicted in groups of two or more, as if they were acting out a play. We try to understand the narrative, unsuccessfully. In Untitled (Smoking Girls), two young women drag on cigarettes in a residential backyard, unaware of any camera. In Untitled (Cat Dissection) femininely dressed teen-age girls dissect a cat, which on first glance looks like a stuffed animal. Untitled (Beth in the Library) depicts Beth draped atop a library shelf, naked. A group of six naked young men and women roast marshmallows in the woods, in Untitled (Roasting Marshmallows). Deadpan and with nonchalance, the images are a collision of obvious and the unexpected, at once visually simple but psychologically complex.

Strassheim’s tableaux vivants bring to mind the adage that “photographs never lie.” But about what are these images telling the truth? Nothing. Strassheim has built a sandcastle of visual information made of tension and unease, a construct that allows us to scheme and create a narrative of our own making, one of which we are in control.