The Long Way Home

Akram Khan Company's touring work, "bahok," was on stage last week at Northrop. Camille LeFevre weighs in on the performance, calling it a moving, elegant homage to the universal, often unfulfilled human longing for a "true" home.

IN THE WAKE OF RECENT EARTHQUAKES IN HAITI AND CHILE that have left hundreds of thousands of people homeless, and the economic travails in this country that have driven families from their homes, Akram Khan’s bahok, originally choreographed in 2008, is both prescient and particularly poignant. Last Wednesday evening, the Walker Art Center and Northrop co-presented the Akram Khan Company (the company’s first Minnesota appearance) in the 60-minute work about home and hope — the last two words, not so incidentally, that appear on the large electronic sign hanging above the stage.

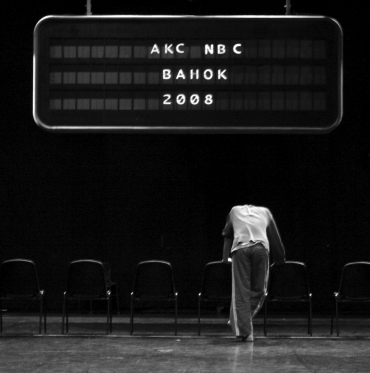

The sign is a prominent feature in bahok, and its placement is indicative of liminality, set in a departure lounge of indeterminate origin (for a train? a plane? a ferry?), a waystation from which the eight dancers may be leaving or returning home. The sign, often black and quiet, periodically surges to life displaying a digital jibberish of rapidly changing orange letters, numbers, and punctuation that causes the performers to stop their luscious, fluid choreography or vignettes of spoken text or physical altercation; when the sign comes on, they all look up, as if in the hope of finding some direction home.

Instead, they see “Please wait,” or “Delayed” or “Rescheduled.” An ennui we’ve all experienced, while waiting to get somewhere other than here, permeates the work. One fellow darts animatedly across the stage while talking loudly on his cell phone, then shushes other people who are talking. A mentally disturbed young woman obsesses over her scraps of paper and annoys other, bored passengers with her questions. The work is infused with the desire to bust out of an interminable holding pattern; fantasy is one way to go.

One couple — she intensely sullen when not merely limp, he obnoxious and confrontational — are released from their painfully restrictive personas in a duet of gymnastic sensuality. Their bodies intertwine in ever-more complex renderings of passionate embrace, until they resemble a single creature — one that’s not quite human, and yet which embodies an expression of pure intimacy. Meanwhile, the obsessive young woman with the paper scraps suddenly reels across the floor with leaps, turns, and flips in a physical expression of exuberance unleashed.

The characters also break out of their malaise by bringing memory to life. In one spoken vignette, a woman attempts to explain to an (invisible) immigration officer who her South Korean companion is and why he’s traveling, alternately encouraging her companion to speak up and to be quiet, as the tension builds in this deftly rendered duet.

Other performers enlist each other in having some fun — a ballet dancer cajoles her companion into snapping pictures of her, recruiting the cell-phone talker to stand in as her partner for her arabesques and demi-pointe turns. Such kinetically generated humor is countered by moments in which a fight breaks out, only to resolve in a group hug that’s anything but saccharin: as each of the dancers gently envelopes the others, the usually quiet young woman is left out; her vaulting attempts to insert herself into the group are touching.

________________________________________________________

The performers cross, turn, and thrust their limbs in waves of continuous phrasing, communicating a single desire: to be set free from this place and to find a way home.

________________________________________________________

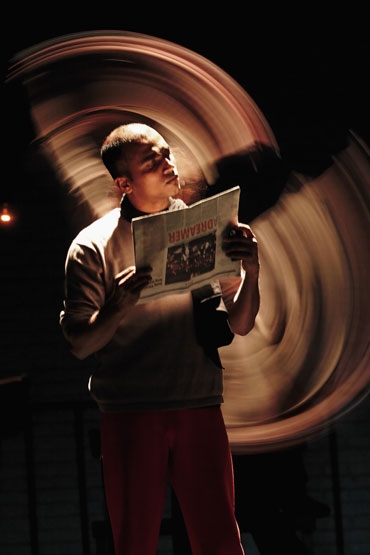

Khan’s choreography is a movement vocabulary of resilience and flow, performed by the company’s dancers with a crystalline liquidity that becomes these characters’ universal means of communication. Long limbs stream through space, punctuated by glorious flourishes of the hands and feet. Bodies twirl and arc in a yearning for movement not afforded the characters stuck in a purgatory of endless delay. Dancing in unison to the pulsing sections of Nitin Sawhney‘s score, the performers cross, turn, and thrust their limbs in waves of continuous phrasing, communicating a single desire: to be set free from this place and to find a way home.

The word “bahok” is Bengali for “carrier,” the implication being that the idea of home we carry with us — regardless of where we are — defines us, separates us from one another, but can also bring us together. As people, and as characters, in bahok the dancers represent a global potpourri of cultural origins: They hail from Spain, South Korea, Slovakia, South India, South Africa, and Taiwan. (Khan, who doesn’t perform in bahok, is a British choreographer of Bangladeshi origin. And while bahok was created in collaboration with the National Ballet of China, many of the original dancers from that company were not available to perform on this tour.)

The idea of home — especially for these artists who, when they appeared on Northrop’s stage, were on the last leg of their United States tour — is perhaps one that’s continually in flux, but consistently underpinned by a deep longing for a true place of origin. “I’m a foreigner, like you,” one performer says to another. And when you consider the widespread economic ruin of these times, the devastations caused by acts of nature or political machinations, we’re all displaced in some sense, left with an idea of home rather than its tangible counterpart, a haven that lives only inside our psyches, our souls. Yet we’re co-habitants of one world, Khan seems to say; the sign above the stage asks all of us, “What are you carrying?” On the best days, home and hope.

________________________________________________________

Noted performance details:

bahok by the Akram Khan Company, copresented by Northrop Dance and the Walker Art Center, was performed at Northrop Auditorium on March 3.

________________________________________________________

About the author: Camille LeFevre is a dance critic, arts journalist, and college professor.