The Floor of the Sky: Both Earthy and Light

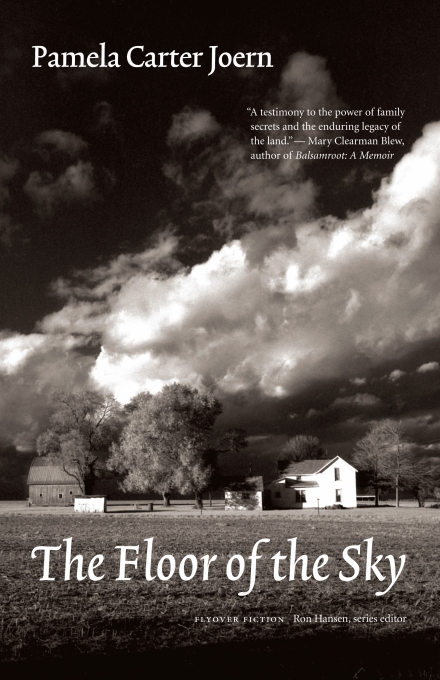

Jean Sramek read Pamela Carter Joerns book ("The Floor of the Sky," from Bison Books, University of Nebraska Press) and admired its subtle clarity.

Teenage pregnancy, sustainable family farming, rural drug abuse, Alzheimer’s, and sibling rivalry. Pamela Carter Joern deals with all these contemporary issues—and a few others—in The Floor of the Sky¸ the story of a broken yet fiercely loyal ranch family in rural Nebraska. Carter Joern manages to examine these topics, even make statements, without being ham-fisted or preachy. On the contrary, her touch is so light as to be mischievous, and we are often left wondering (in a good way) about this message, or that—or whether there was a message intended at all.

The story of generations of the Bolden family, owners of the Bluestem Ranch, are told through the eyes of those left living. The primary narrators have come together out of necessity. Toby Bolden Jenkins is the 72-year-old grandmother, Lila her pregnant 16-year-old granddaughter. Lila and Toby taking turns telling the story of this too-short summer from their own perspectives, their chapters interspersed with chapters told by Toby’s crotchety sister Gertie and Toby’s best friend George, the Bluestem’s hired hand. There is no table of contents, no page numbers for chapters—the story simply flows from headings labeled “Toby” and “George” and “Lila” and “Gertie” back to “Toby” again. It’s as though the author is coaxing you to read it in one sitting, without the benefit of a bookmark. That’s not a bad idea.

Lila has been banished to the Bluestem by her jet-setting Minneapolis mother Nola Jean, who views Toby as the convenient proprietor of an unwed-mothers’ home where Lila can sit in the proverbial corner and think about what she’s done, or as Lila puts it, Mom sent me here because she can’t stand to look at me. Toby does not resent this, and is almost glad for the company, a welcome break from Gertie’s bitterness and the impending guillotine of the back taxes on the Bluestem, which Toby cannot pay.

There are subplots as well—Gertie’s husband Howard slips further into nursing home senility, Lila’s adored older cousin Clay is sleeping with a married woman, a ranch couple named Julia and Royce grow organic beef on the land they lease from Toby. This book is populated by characters both living and dead, and the Bolden family graveyard is full of secrets. Some of the secrets are in plain sight, but living Boldens who refuse to see them or talk about them are not so very different from any given non-fictional family.

Some of the story is predictable: pregnant girl comes to terms with “who she is” by bonding with her grandmother; quirky people from small town are sometimes trouble and sometimes salt-of-the-earth; megalomaniac patriarch Luther Bolden ruins everyone’s lives even after death; heirloom jewelry and framed photographs invoke memories. That kind of thing. But The Floor of the Sky never divulges its secrets too soon or too obviously, and Carter Joern is masterful at showing-not-telling, that traditional writer’s mantra. Clues and hints about Bolden family truths are dropped like feathers, and when we find out what we suspected we knew—a baby born out of wedlock, a murder, an accidental infidelity—it still feels like a surprise. Not all is revealed, either. Some secrets are taken to the grave, some grudges not only kept but honed, and it’s all presented in a prose that is at once earthy and light:

Eleanor bore him four girls who all died the same winter of diphtheria. Robert Bolden built four small pine coffins, laid the girls out, tucked in with dolls and teddy bears, dressed in pinafores and calico dresses made by Eleanor’s own hands. The coffins had to be stored in the horse barn until the ground thawed in the spring, and most days Robert found Eleanor draped over one or the other of her darlings’ caskets, eyes dry and vacant, mouth slack with grief. In March Robert chose a spot in his own pasture, fenced it off, dug four graves, and lowered his daughters into the ground while his still ailing and depressed wife clung to his arm and wept …. Five years later, after two miscarriages, Eleanor gave birth to one more child. A boy this time. Luther. Eleanor looked at her new baby, turned an exhausted face toward Dr. Blackford, said, There now, Robert has his son, and died.

The standout character is Toby. Carter Joern avoids heroic clichés about elderly women, and if Toby is caring and wise towards Lila, it’s because Toby is Toby, not because she’s a grandmother. Toby is full of self-doubt, masturbates to the memory of her first lover, quietly drinks whiskey out of a coffee cup, and thinks badly of others, especially her sister:

Gertie sits at the kitchen table. She’s dressed for town in one of those outfits old women wear, two-piece polyester, Wal-Mart or K-Mart specials. Peach pants, a white blousy top with peach, mint and blue flowers made of twisted ribbons. Washable, lightweight, and cheap. Toby refuses such clothes, making her mind up, as she has throughout her life, not to be like Gertie. Ten years older than Toby, Gertie’s her advance warning, her red light flashing. Instead, Toby wears a plaid cotton shirt, tails out over the bunchy elastic waistline of her jeans. She does allow herself elastic. She’s not a fool.

The book has a few awkward flaws—characters’ names change from one chapter to another, and a climactic scene is marred by the assertion that money has been “invested in the Standard and Poor Index”—which are hardly worth mentioning, except that in a book so finely combed, it’s sad to see lapses in fact checking and proofreading. However, Toby and Lila are a winning combination and this is a very satisfying novel.