The Dancing Camera

Lightsey Darst reports back with some critical reflections on this year's Dance Film Project offerings, part of the annual Minnesota Dance Film Festival (organized by John Koch and Vanessa Voskuil) that took place December 11 - 18.

VANESSA VOSKUIL AND JOHN KOCH HAVE DONE A GREAT THING in starting the Minnesota Dance Film Festival. Dance film is a hot and growing genre, one that the Twin Cities, with its thinky dance and vibrant indie film scenes, seems naturally poised to excel at. The festival’s main event, the Dance Film Project, an unjuried screening of dance films made in the past year, draws enthusiastic responses from all over the dance community, highlights new or little-seen artists, and spurs the creation of new work. But Voskuil and Koch aren’t content to stop with this one event; this year’s festival also included a retrospective and screenings of Pina Bausch films; in the future Voskuil and Koch hope to include commissions, guest artists, workshops, and more.

I want to make it abundantly clear that I support the Dance Film Festival before I head into reviewing the Dance Film Project. The festival is not what individual artists created in response to the call for entries; the festival is the great opportunity they were given. Have we squared away that distinction? All right then, the films: so many (24, by my count, plus two live performances), and so various — by the end my head was spinning. Rather than try to assemble all the variety into some larger idea (which would be like sculpting an Arc de Triomphe out of crocodiles), I’ve just cobbled together some notes on the menagerie. Away we go.

First, a (stab at a) definition. “Dance film” is not merely dance documented on film. Instead, it is something other than what you can see in a theater. The key feature of dance film is the dance created by camera motion and editing.

At the Dance Film Retrospective, someone described dance film as “a match made in heaven.” It’s easy to see why: dance loves motion, the camera loves motion. Plus, film promises to solve a couple of dance’s enduring problems: the fleeting nature of the art form and the necessity of placing and playing to the audience.

If you, like me, just went to see Minnesota Dance Theater’s Nutcracker, though, you might disagree on whether these are problems. A great part of the charm of that very charming production is its aliveness: the feeling that these dancers are here, breathing the same air, aware of and dancing for me. And the expansiveness of the MDT production is another of its charms: the way the dancers’ motions take in the entire audience, joining several hundred people in a single sweep of the arm. If you solve the “problems” of ephemerality and stage limits, you’ve got to find something new to offer the audience, in place of life and community.

Also, if it’s clear what film gives dance, it’s not so clear what dance gives film — a moving target? Ultimately, there are no shortcuts: the best dance films succeed as dances and as films.

The worst dance films, on the other hand, are self-parodyingly bad. “We are dancers! Behold how we noodle about in our specially sensitive dancerly way!” they scream.

They make one want to lay down a few rules about dance film, to wit (with, of course, exceptions):

Rule 1: Just because something can only be shown on film — fine movements, extreme close-ups, dancers in nature — doesn’t mean it should be. Particularly the dancers in nature. Enough with the dancers in nature.

But, in the area of things that can only be shown on film, consider Renata Sheppard’s entry, The Wait of Gravity, in which a dancer spins, tosses, and cavorts on a plexiglass structure. Are we seeing her from above, below, the side? Locating the down direction takes most of the piece, and it’s more fascinating than you would think, as it leads your thoughts through a consideration of how weight looks and feels, of what is possible in our physics.

Rule 2: The beauty of beautiful people is not in itself sufficient reason for a dance film.

But Brian Evans taking his shirt off in silly strip-tease slo-mo in Jaime Carrera and Tyler Jensen’s Hustle — that joke pays its way.

Rule 3: It only seems like a good idea to bring in that tremendously evocative symbol, the one that means just about everything (the sea, for example), and let it sit there on the screen. Symbols like that don’t power your work — they master it.

But then there’s Vanessa Voskuil’s Overflow, which revels in a red tide of satin, summoning up suicide, sex, childbirth, rebirth in a potent mix. Voskuil’s not just messing around; she has these themes at her fingertips, like notes on a keyboard, and she weaves them in a haunting spell. This film breaks more rules than one: close-ups of Voskuil smooth over the calligraphic lines of her shoulders and chest, but these moments reveal character (strength latent under beauty) rather than simply indulging vanity. And Overflow wins the “only on camera” prize by running backward a film of satin being pulled from the floor, an obvious device that still mesmerizes as the satin pools, glimmers, and advances, as if it were alive.

As always, for the best work, no rules apply.

________________________________________________________

Being flummoxed is always fun. Dance film, two arts in one, offers extraordinary opportunities for upheaval.

________________________________________________________

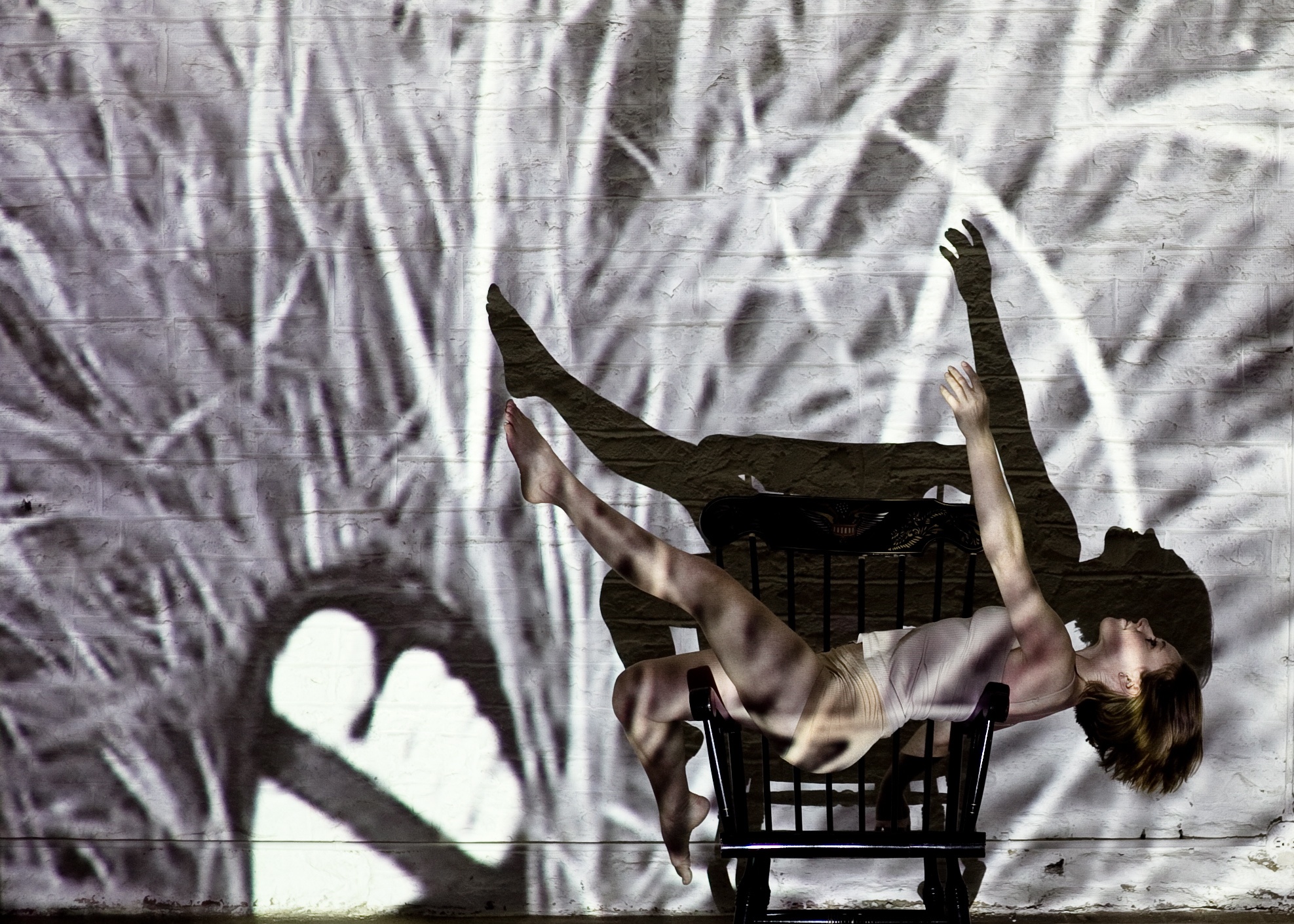

Let me pick up a dropped stitch. Trompe l’oeil — an effect that dancers, with their continual quest for physical truth, deeply distrust — comes naturally to dance film. Sheppard’s strange gravity, Voskuil’s satin: the presence of impossibility, you’re-not-seeing-what-you’re-seeing, is key. Both the live performances employ similar effects. In Shawn McConneloug‘s SubVert, a woman eats cicadas from a sardine tin, finds a three-toed diva, and cuts a hole in the roof of the Southern. Paula Mann and Steve Paul’s Oh the Humanity gleefully confuses the eye with multiple Manns dancing on top of each other: real life Mann, Mann projected (sometimes on real Mann’s white clothes, sometimes on a screen, sometimes doubled), and real Mann’s shadow. It’s a coma of echoes, a cause and effect tango. The most resonant moments of Dawn Strom’s Rocking Chair Sight work a similar vertigo, as the film jumps to slides of Strom sitting still looking at us while a projection falls across her, as if the back wall of the theater had come to life.

SuperGroup Dances in the Face of the Shelf They Built Last Year and Also Builds Another Little Tiny Shelf might be emotional trompe l’oeil. It’s SuperGroup, so it’s funny, right? Everyone laughed on cue at the title, anyway, but then people didn’t seem to know how to react to the piece itself: SuperGroup (a coed quartet of buoyant young people) build a shelf and do what in my notes I called “doofus movement” (awkward-looking ballet-lite this-n-that), all in black and white and to some threatening classical music, while in a dark, possibly pretentious and possibly silly visual framework — a set of sketched-in shelves on which multiple levels of SuperGroup do their thing. It’s so absurd as not to be funny anymore, which I like.

Another wonderfully confusing ride comes from Jessica Ashley Nelson, whose Dance des Petits Cygnes Variation consists of ballerinas reciting the French names for the steps they would be doing in the actual little swans variation (you know, the cute one where they hold hands and bob their heads in unison), while musicians air-play the tune. Sounds like a gimmick, but the experience isn’t. At first, Dance des Petits Cygnes Variation is a bit off-putting: the ballerinas use French accents (which people in American ballet class ordinarily do not); the camera zeroes in on their young faces, which look, in black and white and with their hair pulled back, pure and fanatical; the musicians overplay the agony of the strings; everything is dreadfully serious. But the underlying joke can’t be squelched. Portentous numbers and music (not the dance of the little swans, unless it’s been sent through a somber filter) pile on, until the whole thing arrives at a moment of irrepressible camp — seriousness crumbling under its own weight. But then, directly after I found myself giggling, I got caught up in the weirdness of speaking in unison (that zombie tonelessness!) which led me to the oddity of dancing in unison: why can we barely endure one, yet love the other? And then I was off to some other thought and mood.

Being flummoxed is always fun. Dance film, two arts in one, offers extraordinary opportunities for upheaval.

Q: WHERE DOES DANCE FILM END AND MUSIC VIDEO BEGIN? I suppose the doctrinaire answer would be something like “Music videos serve the music; in dance film, the music serves the film,” but really, several of these pieces flew by with the poppy pleasure of music video. Watching Carrera and Jensen’s Hustle — a cleverly edited showcase of dancers going from pedestrian to dance and back again (Sally Rousse vacuuming, rising into a pensive arabesque penchee with the vacuum sweeper as partner, then returning to her chores) — I found myself making a mental note to iTunes that jingle (Hot Chip’s “We Have Love”). Now, it’s not that I have an answer to this question, or that I think we can find some hard-and-fast delineation, but it’s a question practitioners might consider. Otherwise, look out, gang, here comes Lady Gaga.

If music was the big winner, choreography was the loser. A choreographer in the audience expressed her frustration: “Where’s the movement?” Movement, in the sense of full-body dance phrases, is inimical to the dancing camera, which has to stay relatively still and far away to convey this. Most dance films blithely ignore the problem, settling for a few bits of dance here, a turn or contortion there. But — perhaps I should add this to the rules above — everyone can do and everyone has done an interesting turn or contortion or two, and although the preciously noticing eye of the camera would have it otherwise, people do perceive these moments of beauty in themselves and others. (Otherwise, what natural taste would dance build on?)

Laura Holway’s clever 390,566 shows one solution: we see a whole phrase, but the movement is cut across four dancers in various situations. The man at home straightens up, the woman in the dog park takes off running, the woman in the library crashes into the stacks, the man in his driveway gets dragged by his car. What happens in one shot, in one location, causes the next motion in the next location. I especially loved how this made me, the viewer, assemble the phrase in my head.

Maybe I should say something about narrative, too. A hint of it always helps — narrative, or situation, some context, some expectation. It’s film, after all, which everyone is always saying is poetic, but which — let’s face it — is really the most powerful storytelling medium we have. Poetic moments in film draw much of their poetry from their narrative context, from our learned awareness of what that one gesture means, of how to read that shadow in the dust. Zhauna Franks and Jenna Pace’s Abandon is by no means perfect, but the characters Franks embodies — the innocent in a yellow sundress, the grown woman, the moss-haired hag, the harlot — give us a handle on the scenes and inflect the lush, acid-green landscape with human emotion and life.

Speaking of that lovely landscape, all these films look good. Everyone has good equipment, everyone can shoot, everyone can edit. All the blades of grass are in focus, all the stray hairs glow. Really, the technology is amazing. It’s so amazing that at times it feels facile. I miss the ever-present failure of real-life dance. I miss the Marley lines on the floor, the visible effort.

Still, there are some moments that linger with me: Hands reaching, folding, playing in bright sun in Jenny Pennaz’s Teach Me How to Reach the Sky. The slowed water-flow that looks like hair, cobweb, cloud, in John Koch’s Today (Revisited). The older male ballet student whose carefree skips across the street turn into one floating ride, thanks to creative cutting, in Renata Sheppard’s An Ordinary Man. The Weeki Wachee mermaids, confident and strong underwater, just girls on land, in Mike Hallenbeck’s edit of Henning Gabrielson’s vintage footage. And in Anika Eide’s Shifting Pitches of Sirens, a modern mermaid, her hair streaming out behind her as she arcs upside-down through blue.

_______________________________________________________

Noted event details:

This year’s Minnesota Dance Film Festival took place in Minneapolis December 11 – 18. You can find out about each of the films and filmmakers included in this year’s Dance Film Project on the Cinema Revolution website.

________________________________________________________

About the author: Originally from Tallahassee, Lightsey Darst is a poet, dance writer, and adjunct instructor at various Twin Cities colleges. Her manuscript Find the Girl has just been published by Coffee House; she has also been awarded a 2007 NEA Fellowship. She hosts the writing salon, “The Works.”