The Captured Image: Photography Beyond Grain and Pixels

Hannah Dentinger reviews the show The Captured Image at the Duluth Art Institute (in the Depot building, 506 W. Michigan Street, Duluth; though Sept. 30). Shes engaged by the range of techniques in the show.

Curator David Hodges has often been asked to explain the technical processes underlying photographs exhibited at the Duluth Art Institute. For this show, therefore, Hodges selected artists whose work draws deliberate attention to the technical aspects of photography. The exhibition poses the familiar question, “which is better, digital or film?” Then it transcends that dichotomy. “The Captured Image” shows that in photography, as in other media, continuity is as vital as innovation. The contributing artists use a mixture of digital and traditional technologies to create works of enormous diversity and interest.

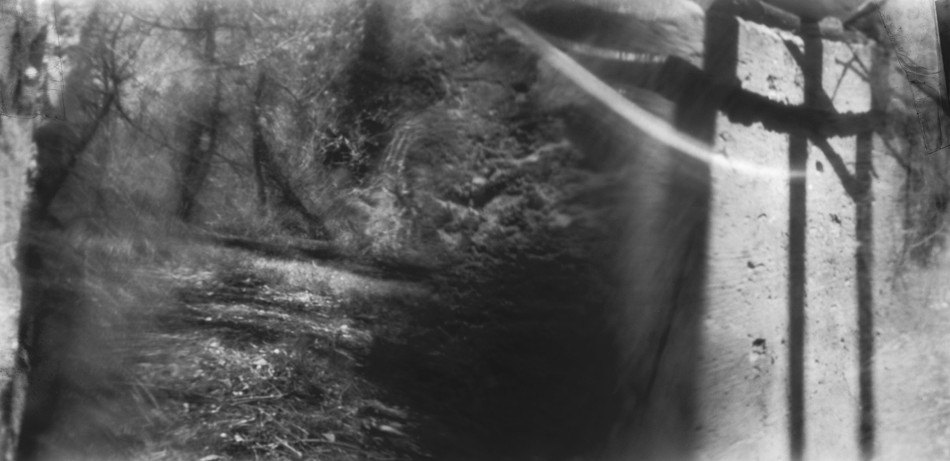

Su Legatt, who has recently moved to Duluth, devised a unique method that combines low-tech and high-tech elements. She made a primitive camera out of a metal canister with pinhole apertures punched in the sides. A roll of film is curled up within, and the resulting negatives are digitally scanned. Legatt’s images are blurred landscapes in close-up—a forest floor melts into concrete striped with the shadow of a wrought-iron fence in ‘Grill’, and ‘Bridge’ is an ant’s-eye view of what I think I recognized as one of the bridges over Congdon Creek, here almost abstracted to the grain of wood contrasted with crisscrossed metal.

Opposite Legatt’s work is that of Russel Sackson of Two Harbors, who uses digital capture and collage to create the show’s most unsettling images. In ‘Union’, a man and a woman are blended back-to-back like conjoined twins. Blindfolded, they sit in shadow under the glimmer of a baroque chandelier. The photographs are gritty, grubby, and reminiscent of David Lynch’s Eraserhead: surreal, yet characterized by a sense of barely-grasped menace. Sackson told me that his work attempts to “question the integrity of photographs.” Although ways of faking pictures were developed early on, the documentary quality of the medium has been further undermined by digital technology, which allows “nearly seamless” alteration of images. We must view photos with increasing scepticism, yet the emotions they elicit are real. Looking at photographs, Sackson said, “you make a memory of something you didn’t experience.” Is that memory any less powerful because it is prompted by a fabrication? Sackson’s work answers that question in the negative.

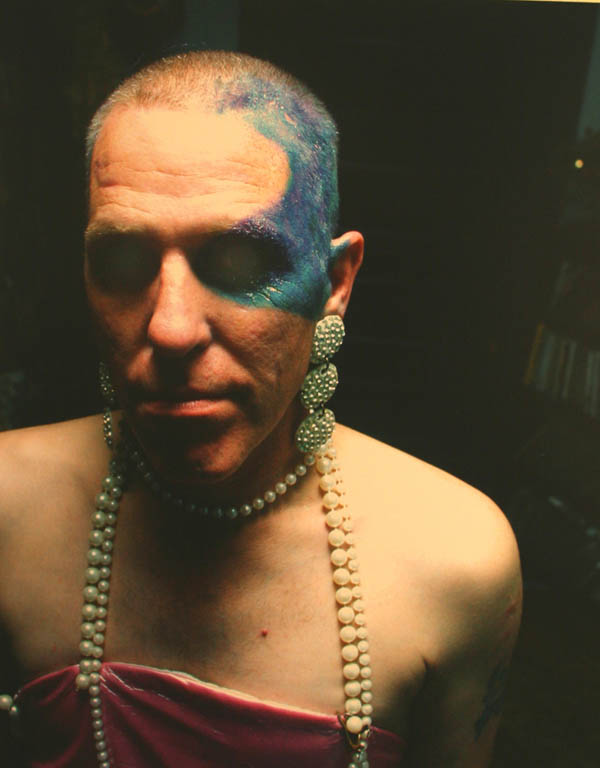

Kristen Mars of Minneapolis contributed glamor shots of elaborately-costumed hipsters to the show. The colors are supersaturated and the prints, huge. “Tim” features a man with buzzed hair, a slinky pink gown and strings of pearls. Sparkling blue eye makeup spreads over the side of his face, appearing to pool like water around his left eye, a jewel-colored bruise. His eyes, nearly invisible in deep shadow, yet give the impression of a forceful gaze. The most interesting photo may be “Rosemary”: a young woman sports a white leather halter top studded with spikes and a voluminous black leather hat woven with wires. A tail of black horselike hair hangs alongside her face. All in all, she has the air of the warrior goddess Athena in punk battle regalia.

Moving away from humankind, Jon Scott Anderson of Kansas City digitally splices six or seven photographs together to create panorama-sized studies of nature. The format was inspired by Chinese landscape scrolls; indeed, Anderson calls his pictures landscapes that he “re-sets” by taking the constituent photos from slightly different angles to disorienting effect. The pictures appear to undulate as the viewer’s eye tries to make sense of the shifting perspective. They remind me of Cubism’s attempts to show all sides of an object at once, or of M. C. Escher’s drawings, in which people meet on staircases that intersect at impossible angles. “Re-Setting Places: Roots, Superior Trail, MN” suggests a root system at such odds with itself that it would be impossible not to trip over it, and “Re-Setting Places: Lake Stones at Naniboujou, MN” is a glossy mass of stones erupting from lakewater that flows over several planes simultaneously.

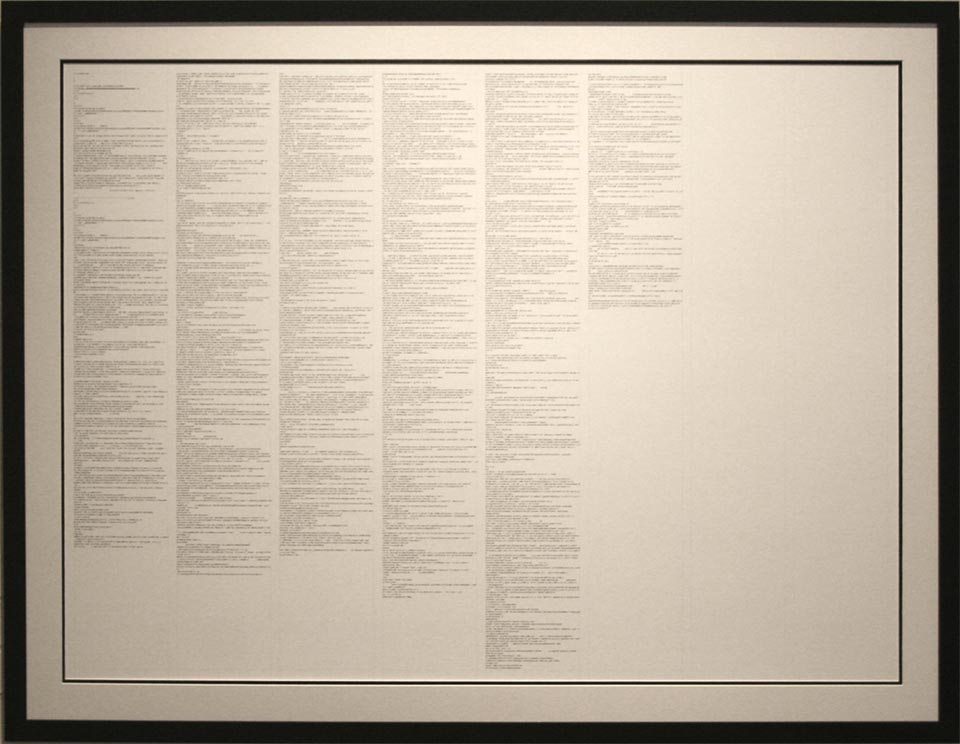

A highly original series of “photographs” belong to Bud Rodecker, a UMD graduate. Amusing titles—“Jennie Lennick with an Alligator Hat,” for example—arouse expectations of something quite different from the rather austere images that greet the viewer: Rodecker’s pictures consist entirely of computer code. The artist chose four images in the ubiquitous jpeg format and arranged the code for each file in columns, putting on display what he calls “the inner workings of a jpeg.” The idea grew out of an experiment Rodecker called “chance photography,” in which he would move bits of code (clumps of pixels) at random within a jpeg file, resulting in what he described as “corrupted photos.” This playful—yet subversive—take on the nature of photography extends to a coffee table book full of pictures of code. In a clever reversal, the index of titles at the back of the book has been replaced with thumbnails of the images themselves. Rodecker isn’t sure if his pictures will sell, but, he told me wryly, they are competitively priced.

The most accessible photographs in the show may also be the most labor-intensive. Keith Taylor of Minneapolis produced exquisite landscapes and cityscapes using a combination of black and white film processed in 1930s developers and digital editing. The pictures are printed on clear plastic, like transparencies, to create platinum prints with a subtle tone and rare luminosity. Taylor’s photos are quiet and reflective—literally so, in the case of “Foshay Reflection”: the familiar shape of the Foshay tower in Minneapolis wiggles up the windows of a nearby skyscraper. “Waves” is the simplest and the most beautiful image in the show. Opaque waters like slabs of slate reflect the glow of a sky hung with clouds. The tiny, gloomy “The Third Bridge” in colors of chalk and charcoal was printed using a process similar to etching, and recalls Whistler’s famous “Nocturnes.” Pictures have never been so motionless as those of Keith Taylor.

“The Captured Image” is at the Duluth Art Institute until September 30. Admission is free. If you are interested in contemporary photographers’ experiments with the array of available techniques, or if you simply want to admire the results, I strongly recommend this fascinating exhibition.