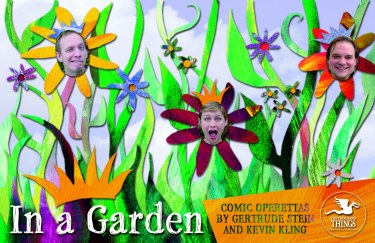

Ten Thousand Things in a Garden

Jaime Kleiman attends her first Ten Thousand Things performance (at Open Book, through April 2) and has expectations dashed.

Maybe it’s because my expectations were too high. Certainly, I expected my first Ten Thousand Things production to be a miraculous event. The fifteen-year-old company’s shows regularly land on critics’ top ten lists and get rave reviews. Veteran actors like Barbara Kingsley and Bob Davis will happily throw away a larger paycheck to perform in Michelle Hensley’s troupe. TTT’s target audience – people in shelters and correctional institutions – adore their work. Prisoners sit, enrapt, on the floor of a gym. Juvenile delinquents take off their headphones and applaud the works of Sophocles and Shakespeare. Homeless people look forward to an hour or two of unadulterated joy. Some of them are seeing theatre for the first time in their lives, and they leave changed. I wanted TTT to change me, too.

In A Garden, which plays March 24-26 and March 31-April 2 at Open Book on Washington Avenue in Minneapolis (see link below for location and ticket information), is a trio of operettas, two by Gertrude Stein and one by local funnyman Kevin Kling. The interludes are performed by Tracey Maloney, Jim Lichtscheidl, and Luverne Seifert, who bound about like kids high on too much sugar. Artistic director Hensley introduced the show by saying that adults don’t have enough play in their lives, and that she wanted to do something silly to contrast TTT’s usual highbrow work. In A Garden is definitely silly. It is also annoying.

The first two vignettes are by Stein, who is clever with words in a staunch, highly intellectual way, and if you like that sort of thing, maybe you’ll laugh. The final and more enjoyable interlude is by Kling, whose imagination produced a feral mermaid, a power-hungry captain, complete with trash-talking parrot, and a pirate.

Michael Sommers’ minimalist set and props convey the appropriate mood with ingenuity. A stand becomes a ship’s mast; benches become mountains and caves; and a piece of yellow wood becomes a murderer’s mask. Sommers, whose company, Open Eye Figure Theatre, knows exactly what to do with this kind of barebones staging. It would have been nice if his puppets had made an appearance.

Operetta is a difficult and moribund genre; it helps if you have good singers and good music. The two men are passable vocalists. Maloney is, well, very loud. What she lacks in timbre, she makes up for in exuberance – but what is she so happy about?

Lichtscheidl, who perhaps has been performing in the revival of his Fringe show Knock! a little too long, brings the same dopey, happy-go-lucky, nitwittery to his part that I recently saw on the Loring Playhouse stage. I didn’t like it then, and I didn’t much like it last night, though his lightheartedness was a nice contrast to Maloney’s overacting, pouting, and generalizing. Maloney’s best quality is her excellent comic timing, which she has used to greater effect in other roles. Lichtscheidl’s choreography was just as playful as his character; he and Seifert perform it well to hilarious effect. (The part where they roll over and pretend to be puppies is an apt metaphor for the show, which, in its saccharine fervor, neglects to find any nuanced theatricality while striving too eagerly to please.)

Then there’s the fact that operetta is, in addition to being outdated, just not very good. (Gilbert and Sullivan and The Threepenny Opera, both precursors to the modern musical, are exceptions). The musicians, Peter Vitale and Jack Matheson, play keyboards and percussion, respectively. They produce some interesting, warped funhouse sounds and provide solid accompaniment to the madness. The music itself verges on the atonal, reveling in crunchy minor harmonies that are, I expect, supposed to be amusing. Usually, it just makes the singers sound gratingly and obliviously off key.

This kind of performance is tricky. It’s broad physical comedy, clownish, and somewhat sophisticated. It should look effortless, not strained. Seifert, for years a presence at Theatre de la Jeune Lune, is in fine form here. He’s funny without being showy, clownish without seeming staged or gimmicky. His energy serves as an anchor to his cohorts’ ping-ponging. He gets it right.

In this world, sight gags, gay laughter, and gooey sweetness thrive. It’s firmly rooted in an adult’s idea of how a child’s imagination works, and nothing bad ever happens. Maybe that’s the point. Ten Thousand Things doesn’t design their shows for jaded theatregoers. Clearly then, this show is not for people like me. I like my humor served cold, on the side, with a well-aimed squirt of irony masking its true intent.