Strong Paint: Three at Gallery Co

Gallery Co, on the seventh floor of the Wyman Building at 400 N. First Ave., is currently presenting three painters: Duk Ju L. Kim, John Salhus, and Tracy Miller. The show is curated by John Hock.

This is a review of a terrific show of paintings in a relatively new gallery space called Gallery Co, at 400 First Avenue N. in the Wyman Building, a space that also serves as the offices of Coen and Partners, a noted landscape architecture firm. Before getting to the paintings, a little digression about Coen and Partners: The firm was recently (August 12) featured on the front page of the New York Times Home and Garden section for its work on Jackson Meadows and Mayo Woodlands, two strikingly beautiful, innovative, award-winning housing developments near Stillwater and Rochester, respectively. The projects are collaborations between the architect David Salmela and landscape architect Shane Coen, who describes his firm’s mission this way: “A priority for all of our projects is to create beautiful ties between cultural and natural systems with lasting social and ecological impacts.”

Judging by the gallery, Coen has retained a generous-minded and open curiosity that keeps invention fresh. He has invited a series of curators to create shows for his gallery space and the results have been consistently fascinating—not always of equal quality, but always of great interest. (The next one—opens September 17–will be paintings by Doug Argue that seem to feature one hell of a chicken as well as other portraits.)

The current show, however, is great. The three painters—John Salhus, Duk Ju L. Kim, and Tracy Miller—all do paintings that are built: regular brick houses of paintings. The show is curated by the sculptor John Hock, the artistic director of Franconia Sculpture Park, and his sculptor’s eye has chosen work that is compositionally and intellectually and even emotionally complex, every stroke necessary in a way that is typical of a good object but doesn’t often have to happen in painting. They have the inevitable quality of living organisms: you feel that every detail is a crucial part of the makeup of this breathing thing, a bone, a wing, a foot.

To talk about paintings like this, it seems important to note that here artmaking has stepped back into the role of parallel universe, of the ghost world of physically embodied meaning that is so necessary to understanding the relation of human and matter, of mind and body, in a cumulatively complex way (that is, art like this enables its viewers to become wiser and more perceptive about the material world in incremental ways).

For some decades art in the West was primarily in the business of being a kind of solipsistic parallel world to the artworld only, concerned primarily with making gestures that redefined the possibilities available to artmaking. Art faced art history, addressed art history as the source of its meaning. Of course in some senses this is always the case, but there’s the open possibility of a greater ambition.

Work like John Salhus’s, for instance, displaces the realm of inquiry from history (or public time) to sensation (private duration). In one series, for instance, he puts down rubs or sweeps of color, overlaid by strokes of thicker color about 5 inches long, seemingly as long as the loaded brush can consistently lay down the paint. Time is not cumulative, not an objective ladder, not historical in this work. It’s a collection of presents (and gifts), a private affair, though perhaps universal. Hock’s curator’s statement says of the work, “Salhus’s process crystallizes as surface, magnanimously proving that his paintings hold true to any value of life’s scheme.”

Salhus’s relentless but graceful stripe and stroke paintings, built according to a process that can be read analytically but that is generously sensuous in texture and color, invite the kind of marveling grandiosity that both I and Hock have been guilty of in describing his work. Forgive it, okay? When you see the paintings you’ll understand.

Duk Ju L. Kim, on the other hand, is equally painterly but even more architectural. Her paintings have strength, muscle, are like a Philip Guston boot but with cartoon nails in it. (Nowadays cartoons are so much more violent . . . .) The sensuality that winds around and out of Duk’s thick forms of power can be such a surprise. This work is grounded in the realities of power and grace and abjection. People seem to understand less and less power’s real nature, real appeal and dangers, the more they succumb to it behind their eyes. Duk puts it frankly in front of our eyes, without a cover story. This work is lovely, tough, immediate, even brutal, but skilled, knowing, and beautifully formed. Something to wield.

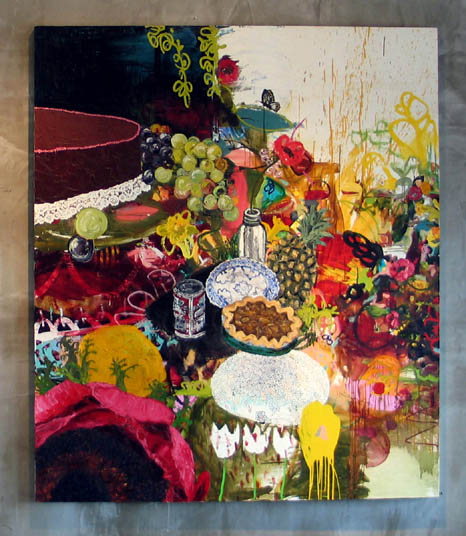

Tracy Miller’s paintings are related, but utterly different. Again, this is complex and layered work, built up over long periods—Miller will leave paintings up for years, adding, layering, building the work. But it all appears fresh, inviting. She paints literal American feasts, layer cakes and petits fours and cans of Bud and doilies and pie. It’s luxury not as excess but as everything. Lots of skillful fun, but with a thread of danger, the lurking Lord of Misrule who can turn Carnival into nightmare (those snarled-line doilies are sometimes black . . . ) Again, it’s a depiction of strong humanness, complexly understood, the delight and the cost of appetite.

This is a thoroughly grown-up show in which painting demonstrates what it can do as an ambitious and mature cultural practice. It’s also, for anyone who likes paint, amazingly fun. Only a few days left to see it—try to get downtown.