Still Standing: Carl Gawboy

Suzanne Szucs interviewed Carl Gawboy about his life and art recently. Carl Gawboy: 50 Years Standing opened at Ancient Traders Gallery on Franklin Avenue in Minneapolis on June 29.

There are some stories you rarely hear. Carl Gawboy told me this one.

In 1852, at the age of 92 or 93 or 94, depending on who you ask, Chief Buffalo traveled from Madeline Island to Washington DC to convince President Fillmore to rescind the relocation order that would have displaced all Ojibwe west of the the Mississippi. He and his companions traveled first by birchbark canoe, transferring at Sault St Marie to steamer, cruising the Great Lakes through Detroit to Buffalo where they changed to rail, only after Chief Buffalo was put on show as an authentic Indian to raise train fare. After 10 weeks of travel they arrived in Washington determined to see the President, but were turned away, until by chance they met a Congressman who arranged an audience and Chief Buffalo persuaded Fillmore to reverse the order of relocation.

In today’s day and age, when cynicism rules, that’s a fine story. One person can make a difference. It is a fitting way to start a piece about Northern Minnesota painter Carl Gawboy who every day tells stories, recounting the history of his people in paintings that intersect with his own life. Gawboy is showing his work at three locations this summer: Madeline Island, Minneapolis, and Grand Portage.

I’d been acquainted with Gawboy, who is located just north of Duluth, for several years and had seen his work here and there, but it was last summer when I heard him give his “Naked Indian” lecture at the Madeline Island Museum that he really got my attention. Gawboy talked about the representation of native peoples. Having taught Indian studies at St. Scholastica for many years, he had become frustrated that his “students didn’t have a criteria for discrimination.” They would bring back images of scantily clad Indians to use in their lesson plans, not thinking twice about how that would play as representation. “Once I gave them the criteria, they couldn’t find imagery anymore where Indians had, well, clothes on.”

The most sadly hilarious image he showed the crowd was of Indians hunting moose, waist-deep in snow wearing only loincloths. The “noble savage” had to be the antithesis of refined whites – romanticized and next to nature – so the clothes had to go, impractical as that was. Just as peoples and territories were somehow “discovered” by the white settlers, as if those places or people had not existed before white eyes set upon them. Frustrating, indeed. Shortly after his talk, I watched the film “The New World”, during which the natives spend their days in full body paint, even when gardening or pounding corn. Yeah, right. It’s like we have to romanticize Indians to feel good about the European role in displacing their cultures – we tell ourselves they were too soft, too natural, too beautiful to survive the industry of progress…

And then there’s Carl Gawboy. Son of a Finnish mother and Ojibwe father (his parents fell in love over books), Gawboy grew up the youngest of 8 children in Ely where his mother inherited a farm. Trilingual in his youth (English, Finnish, Ojibwe) Gawboy began to draw before he could walk and knew he wanted to be a professional artist when he was four. His upbringing was “rural and woodsy” although he went to a “modern” school where he studied “interesting” things. An epiphany came when harvesting rice – “it was as interesting as it gets and my most Indian of experiences.” He decided his work needed to use his own experiences to tell the stories of his heritage. His images would emphasize the everyday experiences of Indians, not dwell upon romantic notions of an idealized people.

“Everything that I paint I actually did or saw… sometimes what I’ll do is move it back in time. It’s something that I have a part in or would try to do it so that I would know what it was like. These things [like getting together a group of students to make a birch bark canoe] gave me insights that I don’t think other people got. My work shows the culture and landscape of the region.”

Gawboy tells the story of his duck-hunting painting. As a young boy, his father took him out in the canoe. When his father spotted a duck, he dropped his paddle, picked up his gun, and shot the bird, then reached back for his paddle that he had expected young Carl to catch and pick up. “But he didn’t tell me, and it floated on…” Gawboy sent the story back to the 1930s and put a woman in the canoe behind her husband. The story is set in motion and a tradition is retained.

Gawboy’s images are matter-of-fact and respectful. There is no false romanticism, rather a love of history and storytelling. Gawboy fell into fine arts study and teacher training at the University of Minnesota – Duluth and then later completed a masters program in Indian studies in Montana. A subsequent internship at the Walker Art Center in 1972 for a large show on Indian art put a bank of hundreds of slides into his lap. “I kept walking backwards into college teaching,” he says, “Every time I tried to get out, those slides pulled me back in.”

Ultimately he ended up at the College of St. Scholastica in Duluth where he became the coordinator of the Ojibwe language program. It was his job to help native speakers learn how to teach. He was to help create curriculum for new teacher training programs; although he says, “I don’t know where it was that Indians decided that schools were the best place to teach culture. That was the worst idea in the world because culture is supposed to be in the community and at home.”

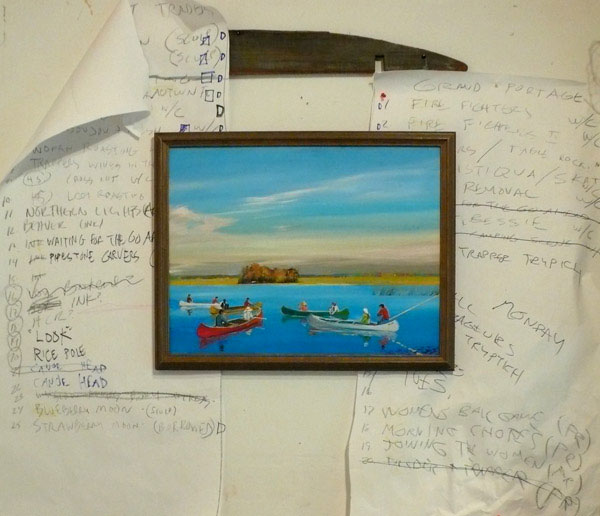

Surely this experience of seeing his students wrestle with teaching Indian culture amid the dominance of misleading imagery has affected his own work and driven him to emphasize everyday life and experiences in his paintings. “Rendezvous at Kitchi Onigam”, the mural he will be installing at the new Heritage Center in Grand Portage this August, presents a double entendre. Whereas there would be an annual gathering of voyageurs and native Americans at the site, what Gawboy really wants you to notice is the rendezvous between sweethearts; an ordinary paddler returning home to his loved one, while others, engaged in everyday activities, look on.

“This was life, people lived here, sweethearts fell in love, everybody did work…”

There will also be an exhibition of paintings at the center, and Gawboy’s two other shows will primarily feature his watercolors and acrylics. Madeline Island Museum is featuring Gawboy’s paintings about Chief Buffalo’s journey to Washington. He’ll be at the museum August 3-4 as part of the program “Traditions and Transformation: Celebrating Ojibwe Art and Lifeways.”

“Carl Gawboy: 50 Years Standing” opens at Ancient Traders Gallery in Minneapolis on June 29th. This exhibition will feature a retrospective of work, including recent collaborations with wood fabricator Jay Newcomb.

When I walked into Gawboy’s studio there was open on his desk a film magazine featuring a new movie called “Pathfinder”. I won’t even talk about the absurd plot collapsing Viking and Indian exploits, but it was yet the most contemporary example of how Hollywood just doesn’t seem able to represent “the other” with dignity. Gawboy laughed and told me the focus of the article was that half his actors got sick – they were filming in Canada and the Indian characters were half naked – so they all got sick and ended up in the hospital.

“The theme in Hollywood is that they always have a white person who is discovering them… they never have Indians telling their own stories.”

Gawboy just wants to get at the truth. If he had it his way, “When people think of Indians in this part of the country, they would think of my work and how I show it.” And if at times he gets a little tired out trying to get those pictures out there, I imagine he thinks of Chief Buffalo and the long trek to Washington – one man making a big difference.

“Carl Gawboy: 50 Years Standing” will open at Ancient Traders Gallery at 1113 East Franklin Avenue in Minneapolis June 29 and will run through September 29. The opening reception is 5-9pm. Gallery hours are Wednesday- Saturday, noon-6pm or by appointment. For further information contact Heid Erdich at 612-870-7555.